Was your client wearing a seatbelt?

Well-known seatbelt defects that may prove the answer is yes!

Your client is in an auto accident. At the conclusion of the accident he is found to be unbelted. During the course of the crash he was thrown about the interior of the vehicle and/or ejected from the vehicle and suffered serious injury. The investigating officer “opines” that your client wasn’t wearing a seatbelt at the time of the accident and checks the box in the Traffic Collision Report indicating “lap and shoulder belt not used.” Your client swears he was wearing his seatbelt.

Many attorneys under this set of “facts” either do not sign up the case or resolve the case for something far less than full value due to the perceived comparative-fault issue. After all, the investigating officer “opined” that your client wasn’t wearing a seatbelt after his “investigation” was completed and further noted in the Traffic Collision Report that the “lap and shoulder belt [was] not used.”

The purpose of this article is to point out the three primary ways an otherwise properly functioning seatbelt buckle can “unlatch” during the course of an ordinary auto accident.

I write about this here for two reasons. One, I don’t want anyone to miss the potential auto-defect case, especially if your client has catastrophic injuries and insufficient coverage from other potential third parties responsible for the crash. Two, if there is a sufficient coverage from a responsible third party, but your client is accused of not wearing a seatbelt, and thus a drastic devaluation of the claim due to alleged comparative fault, you will be armed with some viable theories to rebut that comparative-fault claim.

The three-buckle unlatch defects

• Inadvertent unlatch/release

This is a well-known buckle defect in the automotive industry. This is a scenario where your client is properly wearing a seatbelt, gets involved in a crash and during the course of the crash something strikes the top of the buckle (the red/orange push button used to unlatch/release the buckle) and the buckle pops open, i.e., inadvertently unlatches or releases. It is not uncommon for a person’s elbow in various crash modes to strike the top of the buckle and unlatch it. In a frontal or rear-end crash during the rebound phase, a person’s elbow can strike the release button of the buckle and unlatch it. Similarly, in a rollover crash a person’s elbow or hand can easily strike the top of the button on the buckle during the chaos of rolling over. In addition, objects flying around inside the vehicle during a crash can also strike the top of the buckle and cause an inadvertent unlatching of the buckle.

This isn’t some plaintiff’s “expert driven theory.” It is a reality. The auto industry knows firsthand that in a crash a person’s elbow can strike the top of the seatbelt buckle and unlatch it. As a matter of fact, auto manufacturers’ very own crash testing has proven this precise mode of inadvertently unlatching a buckle.

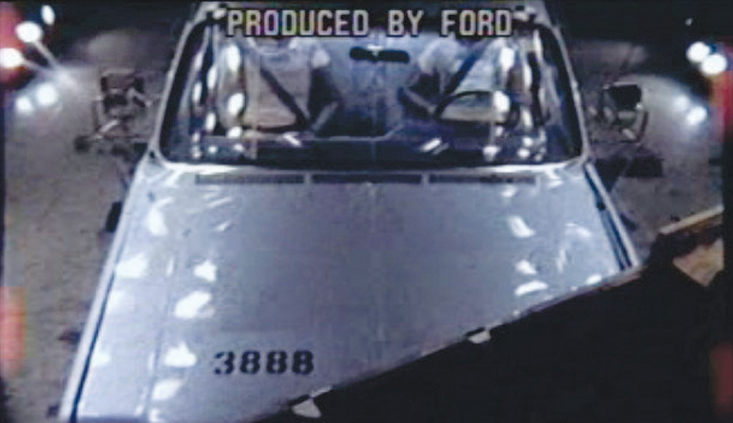

In Figure 2 are two frames from a crash test showing the passenger side-crash test-dummy’s elbow inadvertently unlatching its seatbelt buckle. In the picture on the left the dummy is fully belted and restrained. In the picture on the right, moments later during the course of the test, the crash-test dummy has rebounded back and its elbow has inadvertently released/unlatched the buckle. You can see the shiny object in the picture on the right, which is the tongue of the seatbelt, fully unlatched.

If this were a real-world crash involving your client, the “investigating officer” would have “opined” that your client was not wearing a seatbelt and checked the box in the traffic collision report “lap and shoulder belt not used.”

Due to this situation being a real possibility, the auto industry actually performs testing and has test standards pertaining to minimizing just this scenario from occurring in a crash.

Industry testing with inadvertent release

General Motors by at least 1984 had a standard called “Seat Belt Buckle End Release Ejection Test” which expressly states: “the purpose of this procedure is to determine if a 25mm diameter ball will open a buckle by depressing the push-button release.”

Ford Motor Company’s internal standard in the mid ‘90s was called “Buckle Inadvertent Delatch” which stated: “end release buckle assembly must not release tongue when contact by a 38mm diameter sphere at any location … to reduce the likelihood of the buckle being inadvertently released by an occupants hand or elbow….”

What the test engineers do is rub a spherical ball (Figure 3) over the top of the buckle to see if it can be unlatched. The ball is designed to replicate a person’s elbow. If the buckle unlatches, the buckle fails the test. As an aside, as a general rule the auto industry and suppliers do not like to redesign a part or product when it fails to pass their own internal standards. So, what do they do? Increase the size of the spherical ball of course, so the buckles can pass the test. I have seen buckles that were supposed to pass an internal standard utilizing a 30mm spherical ball. When the buck-le failed to pass that test the auto manufacturer/supplier merely changed the test standard to incorporate a much larger spherical ball of 40mm.

Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 209 (FMVSS) requires in Section 4.1 (e): “Buckle release mechanism shall be designed to minimize the possibility of accidental release.

This issue was also addressed in a 1989 patent: “Seat Belt Buckle,” US Patent 4,797,984 (Jan. 17, 1989) describes a buckle design in which “the upper cover is shaped and dimensioned…in such a manner that the tongue is not unlatched…even when a ball having a diameter of 28mm is pressed against the operated surface of the release button.” According to this patent, “the latching of the tongue is hence not released unintentionally even if the operated surface is pressed accidentally by an elbow or the like.”

Due to all the literature and test standards dealing with this issue and due to this clearly occurring in the auto industry’s very own testing, the auto manufacturer must admit that inadvertent unlatching can in fact occur in a real-world crash. Of course they will deny it ever happened in your client’s crash.

If you are investigating one of these cases, make sure to demand from the auto manufacturer and buckle supplier ALL of their crash testing (design, development, prototype, and certification tests) and take a close look for any buckle unlatchings as depicted above. You will find them from time to time. The manufacturer will object to producing all of this testing and only want to produce the Certification Testing. Of course you will not find any unlatchings occurring in that testing, or at least it is very unlikely. You will have a much better chance of finding these gems in the design and development phase and you need to insist on getting all of it!

The design defect

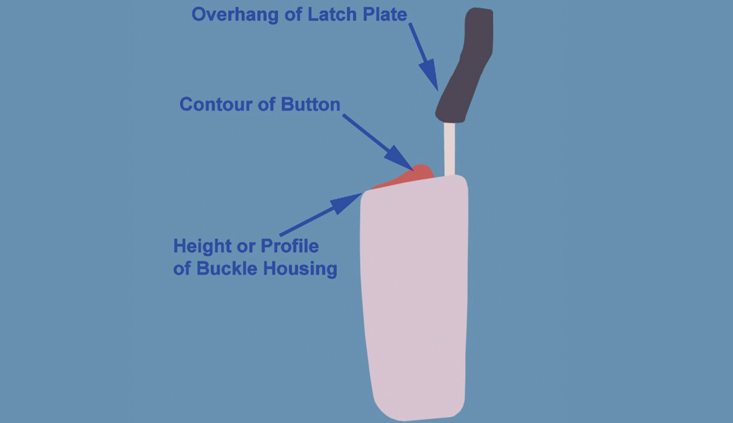

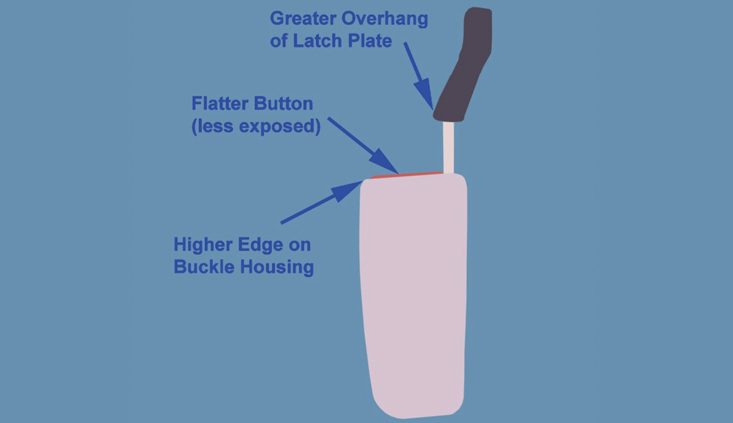

The design defect in these buckles is that the contour of the top of the push button is such that it protrudes up too far out of the buckle housing and/or a buckle housing that is sloped or carved out too low below the top of the release button. This permits a person’s elbow or other object to too easily access the button, push down on it inadvertently, and cause it to unlatch. In figure 4 are two illustrations of a defectively designed buckle and an alternative feasibly designed non-defective buckle.

False latch/partial engagement

This too is a well-known buckle defect theory and well documented in the automotive industry. This is a scenario where drivers think they are properly wearing their seatbelts when, in fact, they are not. The driver inserts the tongue into the buckle until enough resistance is encountered to make it seem that the buckle is fully engaged/latched, when in fact it is not. When the tongue and buckle are in this condition, it is known as a false latched or partially engaged buckle. If an accident occurs when the buckle is so configured, the sudden load forces cause the seatbelt tongue to come out of the buckle and leave the occupant suddenly and unexpectedly unrestrained.

Here again, this isn’t some plaintiff’s “expert driven theory.” It too is a reality. Here again, the auto industry knows firsthand from its own crash testing that this can occur. Accordingly, the Federal Govern-ment and the auto industry have standards that address this defect issue as well.

Depicted in Figure 5 is a Ford frontal barrier crash test where at the outset of the test (pictured on the left) you can see the passenger side dummy is fully belted in their 3-point belt. During the course of the crash test, as the vehicle strikes the front barrier (pictured center and on the right), you can see the tongue out of the buckle leaving the dummy completely unrestrained.

Again, if this were a real-world crash involving your client, the “investigating officer” would have “opined” that your client was not wearing a seatbelt and checked the box in the traffic collision report “lap and shoulder belt not used”.

Industry testing dealing with inadvertent release

As early as 1966 the Federal Government was establishing the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) including “Standards for Seat Belt Use for Motor Vehicles” which addressed the issue of false latching: “Additional requirements for buckles are included to reduce the probability of false latching …” (Federal Register, August 31, 1966, Page 11528, Title 15, Subtitle A, Part 9.)

Specifically, FMVSS 209, Section 5.2(g) states: “A metal to metal buckle shall be examined to determine whether partial engagement is possible by means of any technique representative of actual use.” Additionally, Section 4.3(g) states: “… a metal to metal buckle shall separate when in any position of partial engagement by a force of not more than 22N.” (N = Newtons and 22N is just slightly less than 5 pounds).

In 1974, TRW, a major seatbelt-buckle supplier, had a buckle patented that would design out this defect (Patent 3,807,000 issued April 30, 1974) which expressly stated: “2. … In actual use, it sometimes happens that the wearer mistakes the resistance of the biased latch member, and the firmness imparted to the unlatched tongue by the biased latch, for actual engagement. The wearer then incorrectly assumes that he or she is safely “buckled up”. Such an effect is known in the art as “false latching.” …It is an object of the present invention to provide a buckle and tongue combination free of the danger of “false latching”

For decades Ford has had Worldwide Products Acceptance Specifications prohibiting a buckle from being able to be falsely latched, specifically stating that the “buckle assembly and tongue shall be designed to prevent false latching.”

The design defect

A “side release buckle” is an older style seatbelt buckle that has the push button used to unlatch the buckle located on the side of the buckle. These types of buckles lack a tongue eject feature built into the buckle to spit the tongue out when it is not fully engaged/latched.

An “end release buckle” is the more modern buckle we see in most vehicles today with the push button used to release the buckle on the top of the buckle and are designed so that the tongue should be spit out or be ejected when not fully latched. However, some poor designs can permit the tongue to get wedged or stuck inside of the buckle housing without actually latching and then incapable of being able to pull itself out from the tension from the retractor and/or with less than 5 lbs of force as is required by FMVSS 209. I have seen buckles that can be falsely latched and require 25 to 50 pounds of force to remove the tongue from the buckle.

Inertial unlatch/release

This is also a well-known buckle defect in the automotive industry. This is a scenario where the driver is properly wearing a seatbelt, gets involved in a crash and during the course of the crash, a force is applied to the opposite side of the buckle’s release button. If it is a side-release buckle the force would be applied to the back of the buckle, opposite the push button used to release the buckle. If it is an end-release buckle the force would be applied to the bottom of the buckle, again, on the opposite side of the push button used to release the buckle. This applied force in effect pushes the buckle housing toward the release button of the buckle and causes the buckle to unlatch. In other words, instead of pushing on the release push button towards the buckle, like you would to ordinarily unlatch your seatbelt, here you have the exact opposite occurring with the buckle being pushed into the buckle’s release push button.

Again, this isn’t some plaintiff’s “expert driven theory.” It too is a reality. In the 1990s, the auto industry denied this scenario could occur in a real-world crash. They conceded that, yes, you can have your expert manually strike the back side of a seatbelt buckle and cause it to inertially unlatch, but that that was merely a “parlor trick” and that it could not occur in a real-world crash. However, the industry has since reversed its position on this and now concedes that it can happen.

Unfortunately, I have yet to come across a crash test, like the ones discussed above, where it has been conclusively proved and agreed upon that this scenario has occurred. Additionally, there are no FMVSS that cover this issue. In my view this is the more difficult buckle-release theory to pursue. Due to the lack of a crash test demonstrating it, and the lack of any FMVSS dealing with this phenomena, you have to solely rely on your expert and don’t have the collateral benefits of a crash test, FMVSS, and/or an auto manufacturer’s internal standards addressing this scenario. Now, if you have physical evidence of loading on your belt, you can clearly make this case, it’s just a lack of what I call “objective criteria” from the industry acknowledging this as a major concern that I feel makes it more difficult to get a jury to believe your expert.

Retain an experienced restraints expert

The purpose of this article was not to go into the type of forensic evidence you would expect to see or not see both in the vehicle and/or on your client when analyzing these theories. That would be an article in and of itself.

Regardless, first and foremost, retain an experienced seatbelt expert. I emphasize the word experienced because I have seen time and time again a client that comes into my office who had their case rejected by another attorney because that attorney failed to identify or appreciate a defect. I have seen well intentioned attorneys actually retain an expert to inspect the accident vehicle and then be told by that expert that there was no case. In these instances the attorney did their due diligence and retained an expert to inspect the vehicle. The problem is the expert did not specialize in auto-defect cases per se, but was a more generic engineering expert, well qualified perhaps in general, but not with an understanding in the nuances that appear and can make or break an auto-products case.

In closing, if you find yourself in the situation where it appears your client was not wearing a seatbelt, I encourage you to not stop there with your investigation. If the case warrants it, retain an appropriate expert and have the vehicle inspected to confirm or deny the issue of seatbelt usage. You just may learn, one, that your client was in fact properly buckled up and that you do not have to concede comparative fault, and, two, that there is a viable seatbelt-defect case.

Brian Chase

Brian Chase is senior partner in Bisnar | Chase in Newport Beach. His practice focuses on auto products liability, catastrophic personal injury and mass torts. He is a past president of Orange County Trial Lawyers Association and President Elect of Consumer Attorneys of California.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine