Making complex regional pain syndrome simple for a jury

A start-to-finish strategy for proving the chronic pain and resultant damages of CRPS

When God was testing the faith of Job, the worst punishment was physical pain…. He lost his lands and property, his family – but it was not until physical pain was inflicted that Job broke. (Job 16:6).

A case dealing with chronic pain can be difficult to prove due to the subjective nature of pain itself. This is especially true for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome cases (“CRPS”). CRPS, formerly known as Reflex Sympathetic Distrophy Syndrome (“RSD”), is an incurable chronic pain condition that is often debilitating. For trial lawyers and their clients, this disorder is especially troubling because of the controversy surrounding its diagnosis and treatment. As its very name implies, the disorder is “complex” in nature, is routinely misdiagnosed, and as such, is difficult to explain and prove to a jury.

Take a recent case that had a mixed diagnosis: Some doctors thought it was CRPS, while some did not. In the end, what mattered was our client had severe pain that would likely afflict him for the rest of his life. This was something the jury understood, whether we called it CRPS or not. The primary purpose of this article is to explain the basics of CRPS, highlight some of the challenges in dealing with a CRPS case, and discuss some useful strategies from a recent trial.

CRPS – What is it?

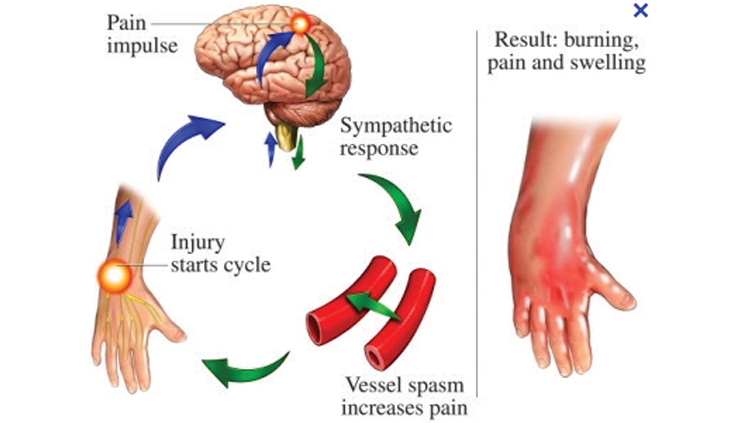

CRPS is a chronic pain condition most often affecting one of the limbs (arms, legs, hands, or feet), in which the pain is out of proportion to the injury. There are two designations of CRPS: Type I and II. Type I, which this article will focus on, is a result of trauma. Type II stems from a specific injury to a nerve.

Some researchers have said CRPS is potentially the worst chronic pain disorder a human being could endure. Doctors describe the severe cases of CRPS as being higher on the pain scale than childbirth and amputation. However, over the years, pain management practitioners were overzealous in diagnosing chronic pain patients with CRPS. In the early 1990s, “RSD” cases were popping up everywhere, perhaps in part due to the unclear diagnostic criteria at the time. Now, after the hype has calmed and thorough research has flushed out a more clear understanding of the disorder, CRPS cases can and should command the same attention as other severe injuries such as brain and spinal cord injuries.

To begin with, CRPS arises typically after an injury or trauma to the affected limb. For example, a seemingly simple fracture to the ankle eventually causing a severe pain disorder in that limb. The most frightening aspect of the disease is that it often initially begins in an arm or a leg and often spreads throughout the body. In fact, according to the National Institute of Health, 92 percent of patients state that they have experienced a spread, and 35 percent of patients report symptoms in their whole body.

CRPS is characterized by prolonged or excessive pain and mild or dramatic changes in skin color, temperature, and/or swelling in the affected area. These signs can be subtle in nature, or dramatic, depending on the severity of the CRPS.

CRPS symptoms vary in severity and duration. The key symptom is prolonged pain that may be constant and, in some people, extremely uncomfortable or severe. The pain may feel like a burning or “pins and needles” sensation, or as if someone is squeezing the affected limb. The pain may spread to include the entire arm or leg, even though the precipitating injury might have been only to a finger or toe. Pain can sometimes even travel to the opposite extremity. There is often increased sensitivity in the affected area, such that even light touch or contact is painful (called allodynia).

People with CRPS also experience constant or intermittent changes in temperature, skin color, and swelling of the affected limb. An affected arm or leg may feel warmer or cooler compared to the opposite limb. The skin on the affected limb may change color, becoming blotchy, blue, purple, pale, or red. As discussed in more detail below, due to the complexity of the disorder, CRPS cases are often overlooked, misdiagnosed, and not properly worked up.

Vetting a CRPS case

As trial lawyers, we appreciate that many of our clients do not have the type of medical treatment and insurance required to get a complete medical workup and diagnosis. Often, an injury like a brain bleed or spinal fracture might go misdiagnosed. With a disorder such as CRPS, this is truly one of the injuries that often require an attorney’s eye and attention to appreciate the client’s dilemma.

The following are a few points to consider when interviewing a client to determine if he or she potentially has CRPS:

• An injury causing pain which is out of proportion to injury,

• Changes in skin texture on the affected area; it may appear shiny and thin,

• Abnormal sweating pattern in the affected area or surrounding areas,

• Changes in nail and hair growth patterns,

• Stiffness in affected joints,

• Problems coordinating muscle movement, with decreased ability to move the affected body part, and,

• Abnormal movement in the affected limb (most often fixed abnormal posture, or tremors of the affected limb).

For a full CRPS potential case checklist, please contact the author.

What causes CRPS?

Doctors aren’t sure what causes some individuals to develop CRPS while others with similar trauma do not. In more than 90 percent of cases, the condition is triggered by a clear history of trauma or injury. The most common triggers are fractures, sprains/strains, soft tissue injury (such as burns, cuts, or bruises), limb immobilization (such as being in a cast), or surgical or medical procedures (such as needlestick). CRPS is essentially an abnormal neurological response that magnifies the effects of the injury. Some doctors explain that CRPS functions in the way that an allergy does. Some people respond excessively to a trigger that causes no problem for other people.

CRPS diagnosis and prognosis

There is no single diagnostic test to confirm or rule out CRPS. In 1994, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) came up with an agreed upon “diagnostic criteria” which most practitioners now use. A diagnosis is made based on the patient’s symptoms and signs that match the description of CRPS. For this reason, oftentimes physicians seeing the same patient may have different opinions as to the diagnosis of CRPS.

With respect to prognosis, research exists that there is no cure for CRPS, while other research suggests that in a majority of cases the disorder may improve over time. The prognosis is highly dependent upon the individual’s particular situation and severity of symptoms. Research suggests that early treatment is helpful in limiting the spread of the disorder, and that younger people typically have better outcomes than older people. The sad reality is that CRPS is difficult to treat and many times patients are faced with a lifetime of unrelenting pain.

How to deal with conflicting CRPS diagnoses

Given the complexity of CRPS, and its somewhat subjective diagnostic criteria, frequently there will be conflicting diagnoses in a CRPS case. In a recent trial, we had a client that was diagnosed by our Pain Management expert and CRPS expert as having “CRPS.” How-ever, the treating doctors never diagnosed CRPS and, in fact, a Kaiser physician opined in deposition the patient did not have the disorder. The question for us going into the trial was “how the heck do we deal with these conflicting opinions about the diagnosis?”

After conducting a focus group on this issue, it became clear that the jury did not care so much about the technical diagnosis of CRPS. What they focused on was simply the “pain.” The jury understood “pain is pain” no matter what you call it. No doctor in the case disputed that our client was in chronic pain. The only dispute was what medical name they decided to give the condition. After the focus group, we made the decision to theme the case as a “chronic pain case” instead of a “CRPS” case. While, our pain-management expert still testified he believed our client had CRPS, we chose not to call our highly regarded “CRPS expert” to trial. This approach allowed us to argue CRPS without putting all of our eggs in that basket.

In that trial, the disagreement among the experts (and treaters) about the CRPS diagnosis could have proved fatal to the case. The jury potentially could have believed the relatively inexperienced Kaiser doctor, who did not understand the nuanced CRPS findings in my client. If we put all of our stock in convincing the jury about CRPS, it would have been an uphill battle all the way. Instead we focused on what everyone agreed – that the plaintiff had severe chronic pain.

The diagnosis of pain is simple, and the treating doctors and plaintiff’s experts all agreed that the pain was chronic and had no end in sight. This simplification of the theme of the case proved effective and the jury returned a substantial million verdict for our client.

Voir dire tips in a pain trial

Let’s face it, the most important part of the trial is picking a good jury. In a chronic pain case (whether CRPS or otherwise), the biggest component of your case can and should be non-economic damages. The biggest dilemma we face as plaintiff’s trial lawyers in this context is getting a fair jury that can give substantial awards for pain and suffering. Many jurors say, “Sure, I can be fair,” in an attempt to avoid the dialogue about their true underlying bias. The reality is that many of these jurors are of the mindset that money won’t make the pain go away, so why give the money? It is therefore critical that you expose in jury selection how jurors really feel about giving many millions of dollars to compensate for pain.

While we often think of jury selection as jury “de-selection,” it is important to embrace the concept of inclusion. Get the panel talking in an inclusive fashion about their hesitancy about awarding money for pain to maximize the number of cause challenges. There are many ways to go about doing this, but in my experience, a jury questionnaire can greatly assist in this process. (Contact the author for a sample questionnaire.) Whether a questionnaire is allowed or not, determine who the worst jurors are in terms of their bias against monetary damages for pain. Begin the discussion with the juror who seems the most vocal against awarding pain damages. Engage them in an inviting manner. For example, “Mr. Limbaugh, you said that it is your belief that you cannot award monetary damages for pain, tell us about that.” Of course, this potential juror will wax poetically on his deeply held beliefs that compensation for lost wages and past medical expenses are fine, but money for pain is an outrage. Follow up with him and validate his feelings. Get him to admit that you will have an uphill battle, or that you are starting off just a step behind if it were a race. Lock him down for the cause challenge in as nice a way as you can.

Once you have your first cause challenge locked, move on to the next worst juror who has reservations about monetary damages for pain. Get them talking and use the same approach. Tell them you will be asking for millions of dollars just to compensate for the pain alone. Once your top “haters” are caused out, you will want to see which other jurors are now willing to share their feelings on this issue now that they have seen others open up about it. What happens during this process is that jurors realize it is socially acceptable to share these anti-lawsuit, anti-damages feelings, especially while you are encouraging them to do so and making them feel accepted as a result.

The next step is to get people who seemed to be decent jurors on first glance (whether on the questionnaire or initial responses in group discussion) into the discussion and flush out any reservations about giving millions of dollars for pain. The goal here is to really bait these people you may be unclear about to see if they will admit to you that they are a little unsure if they could give a substantial award on the issue of pain. After starting with the most anti-pain damages jurors and hopefully locking down your cause challenges, open it up to the group, in a nice way, and say something like “does anyone else feel the way Mr. Limbaugh and Mr. Reilly do, that maybe monetary damages for pain don’t really do a whole lot of good?”

Inevitably, people will start raising hands that you didn’t have pegged previously as tort reformers or low givers for non-economic pain damages. Once three or four people out of your panel start sharing their common beliefs, it becomes much easier for those that are reluctant to share their true feelings to raise their hands and admit that they have some feelings against pain and suffering damages.

Experts: Get the dream team

Due to the somewhat subjective nature of the diagnosis, in many cases the patient does not exhibit all of the typical symptoms mentioned above. It is not unusual for defense examiners to find no temperature changes, edema, or abnormal skin texture, while the other physicians observe such findings. Often times, your client may have shown signs of edema and temperature changes in one visit, but no signs in another. For this reason it is important that your team have a cohesive strategy to effectively handle cross examination, and for you to have a clear plan of attack for the defense expert.

First, you need the best CRPS expert you can find to diagnose the disorder. Typically this is a rheumatologist. The reality is if your client’s diagnosis is sketchy, you want to know up front so you can manage your case appropriately. Each client situation is different depending on the underlying trauma and the severity of what may appear to be CRPS symptoms, and the expert you choose is also case-dependent. Thankfully, there are several CRPS experts in Southern California who are highly regarded in the field. (Contact information regarding CRPS experts is avialable from the author.)

Second, a rehabilitation expert may be appropriate to assess your client’s potential for recovery and to assist with a life-care plan. Many times, the “CRPS expert” may contribute a great deal to the care plan, but having a Board Certified rehabilitation specialist exclusively focus on the potential outcome and future care needs is tremendously helpful.

Third, an orthopedic specialist will be required to discuss the nature of the underlying trauma. In our trial, our first witness was the orthopedic expert who conducted a physical examination of the patient in front of the jury showing the impaired right foot. He described the initial foot and ankle fractures, and pointed out to the jury the skin changes, the swelling, and the redness which are all signs consistent with CRPS. Likewise, the orthopedic expert is useful in describing the first criteria to CRPS – that the complaint of pain is out of proportion to the initial injury.

Fourth, a psychiatrist or psychologist will be necessary to evaluate your client’s mental health situation and future prognosis. When dealing with any chronic pain situation, the psychological aspect becomes paramount. The psychiatrist is also the best expert to explain how the pain signals affect the brain, and how the quality of life will be greatly diminished. As a psychiatrist explained in our recent chronic pain trial, “this patient will endure the rest of his life in pain. Every day for the rest of his life he will have that nerve pain which is a feeling like his leg is on fire. Because of all of this he will be at an increased risk for suicide. We know from the research that patients like this have a higher risk of suicide because they just can’t deal with the pain.”

This expert should testify toward the end of your case-in-chief. This will allow your expert to read and rely upon the trial transcript of your damages witnesses (friends, family, etc.). The psych testimony will then put into perspective from a medical standpoint how the pain is affecting your client’s mental health.

Finally, you will need a life-care planning expert to put together the recommendations of all of the physicians involved to care for your client for the rest of his or her life. The plaintiff’s “minimum life care plan” should include all the future therapies, procedures, surgeries, medications, and assistance to give your client the best chance at having some quality of life in the future.

Dealing with the defense “expert”

In CRPS cases, the defense will likely hire a Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation/Pain Management expert or rheumatologist with experience treating CRPS. This expert will say your client (1) does not have CRPS, and (2) is exaggerating. These doctors will be armed with surveillance footage of your client doing certain activities which they claim are inconsistent with the claims of debilitating pain. When your client has a 100 percent slam dunk CRPS/chronic pain case, the defense will still hire someone to come in and say your client will get better over time. It is up to you to expose the fraud that the defense will try to perpetrate on the jury.

Start with the Defense Medical Examination. The “expert” will likely spend less than 15 minutes with your client, while your Dream Team will have spent hours during their thorough evaluations. Record the session and have it transcribed. Break down how much time was actually spent doing the physical examination portion. It is likely to be less than ten minutes. Make sure that your client is cooperative throughout the examination. Use this as a point during cross exam, that your client was agreeable and did everything that the doctor asked.

Use the statistics. It is imperative to fully research your client’s medical history, complaints of pain, and statistics as they relate to the severity of your client’s CRPS/ chronic pain. Come prepared to the deposition with a list of statistics and force the doctor to agree with your points. For example, “you would agree doctor that CRPS is higher on the McGill pain scale than childbirth, correct?” Or, “You would agree Doctor that there is no cure for CRPS, right?”

Prior to the deposition of the defense expert, create a list of concessions that he or she will be forced to agree with. This goes beyond generic statistics and should be focused on your client’s medical history, course of treatment, ongoing complaints of pain, and future limitations. Even when there is a differential diagnosis, it is helpful to get concessions that your client was active and healthy prior to the incident, whereas now they are disabled.

Making it simple

At the end of the day, pain is pain. It doesn’t matter what you call it. What matters is how severe the pain is, how long it will last, and how it interferes with your client’s life.

CRPS is essentially a nerve-pain disorder. Jurors understand what nerve pain is. Experts sometimes describe it as an “electrical shock” kind of pain with burning sensation. Persuasive testimony from friends, family, and co-workers to describe your client’s everyday life and the pain they endure will hold a lot of weight in the eyes of the jury. Highlight the physical activities that your client enjoyed prior to their injury that they can no longer perform. The simpler you make your theme, the easier it will stick in the minds of the jurors.

Spencer Lucas

Spencer Lucas is a trial lawyer at Panish Shea & Boyle and specializes in litigating catastrophic personal injury, products liability and wrongful death cases. He has received numerous recognitions for his work including being named as CAALA Trial Lawyer of the Year Finalist (2014) and CAOC Trial Laywer of the Year Finalist (2011). Mr. Lucas is from Seattle originally and graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in Business Administration. He graduated from Pepperdine University School of Law and has been practicing since 2004. He has been a board member of the Los Angeles Trial Lawyers Charities (LATLC) since 2012.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine