Empowering the damages expert with the Reptile theory

The damages expert’s testimony must keep the jurors engaged if they are to award fair damages

The justice system is the public safety net that balances harms and losses suffered with compensation. The law says that when we drive on the highway, we have to watch where we are going and see what is before us. If we do not, and as a result we hurt someone, we are responsible for the harm.

Jack drinks a whisky sour and heads out with his two children. Jack drives his two-ton pick-up west on Carefree Highway into the Friday late-afternoon sun. Jack travels at more than 15 mph over the speed limit. Jack turns his head repeatedly to talk to his children. Jack does not read the sign that shows the right-hand lane is ending and to move to the center lane. Jack looks up and his lane has run out. Jack is heading straight for a car in the right-hand turn lane. He yanks his truck’s steering wheel to the left. He sees the car pull out so as to not be hit by him. Jack’s truck strikes the car in the driver’s door. Jack’s truck launches the car 200 feet down the roadside

Mark, my son, is a front-seat passenger in the car. He suffers severe brain shearing injuries when his head strikes the head of the driver next to him, who dies instantly. Mark is medevac’d to John C. Lincoln Hospital. Mark is kept alive on life-support. We unplug the machines seven days later. Today is the one-year anniversary of Mark’s death. Mark’s six-month-old son at the time, Odon, our grandson, is now 1 and one-half years old.

David Ball and Don Keenan in their now-famous book, Reptile, assert that within every one of us, there exists what they call the Reptile, or inner conscience, that innately cares about right and wrong, especially when it senses danger. The Reptile does not concern itself with plaintiff or defense bars, but with threats that are inherently unsafe. The Reptile answers to a primal moral code that is both personal and communal.

Ball and Keenan depict its inbred self as saying, “I don’t like you. I don’t like me. I don’t like.” Without survival at stake, I sleep. I work only when I have a chance of overcoming a survival threat. Otherwise, that snoring you hear in trial is me… I hate: immobility… arrogance… greed (not mine)… competition (against me)… lying to me (dangerous)… hypocrisy (very dangerous)… legal language (not clear, therefore dangerous)…

Reptile formula

Ball and Keenan offer the formula: Safety Rule + Danger = Reptile.

For example, a driver is not allowed to needlessly endanger the public. Drivers must drive at a safe speed. The only allowable decision is the safest available decision. No second-safest.

The Reptile takes note, for example, of the consequences arising from unsafe drivers. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reported in June, 2014, in their once-per-decade traffic study, that the economic harm from traffic accidents in the U.S. cost society $871 billion a year. The toll in lives included 32,999 fatalities and 3.9 million injured. Still, the Reptile will not be belabored with generalized statistics, but its interest is peaked that these crashes personally cost them an average of $897 each year. They care that those not directly involved in the crashes are made to pay for nearly three-quarters of the costs, primarily through insurance premiums and taxes.

The Reptile cares that people who break the law by speeding cause 32 percent of all fatalities, and 20 percent of all nonfatal injuries. They react to distracted drivers on cell phones, etc. that cause ten percent of all fatalities and 18 percent of all nonfatal crashes. They call 911 on drunk drivers that weave about, and are loath to learn that alcohol-related crashes account for 40 percent of all fatalities. It vexes them that the lifetime comprehensive cost to society for each person needlessly killed is $9.1 million. The Reptile cares that the same may happen to them.

Reptiles on the jury

Ball and Keenan show that waking each juror’s “Reptile” is essential for them to heed the call to action. This is true for both plaintiff and defense attorneys who seek a true and just verdict.

As with any lawsuit, it is the jurors’ duty to compensate the injured party for the harms and damages suffered. Ball brings out that the word “compensate” comes from the old English, meaning “balance the scales.” The weight of the harm must be balanced with a full and fair amount of compensation, or else there is no closure to the harm. Ball explains that the law requires that “nothing else be allowed on the scale – just harm on one side and money on the other. No outside reasons.

However, in recent years, the Reptilian nature has embraced the outside reasons put forth by tort-reform advocates, being made to believe it is too risky to fully and fairly compensate the injured. Ball and Keenan counter however, that the defense’s attempts to tame the Reptile are for naught, for it fundamentally adheres to the law as a survival instinct. Because the Reptile instinctually seeks to guard against law-breaking abuses because law-breakers are dangerous, as soon as the Reptile connects the true threat to self and the community, it reacts. In using the analogy of the Reptile, they put forth that just verdicts are rendered by jurors who rightly embrace the law, rendering tort-“reform” fears impotent and unneeded. The Reptile is not concerned with plaintiff or defense disputes, but only with how the “true” harms and losses may pose a threat to itself or the community at large. Even so, the Reptile is keenly sensitive to predators, whether they come in the guise of plaintiff or defense attorneys who seek to undermine the law. The Reptile trusts the law, not those with usurping motivations.

The problem is that during the course of the trial, the Reptile easily falls asleep if it senses no lawful danger. The Reptile knows when it is safe to sleep. Because of this, it is incumbent upon the attorney, plaintiff or defense, to continually wake up and reinforce the Reptile throughout the trial. Never is this more needed than with the extended damages presentation. Unfortunately, vocational economic damage experts are often under-utilized, or worse, disconnected entirely from the larger context. This easily happens as many experts get mired in technical jargon and theory debate to the point where their testimony disengages the Reptile.

The damages experts

Thus, empowering damages experts with the Reptile is paramount to maintaining a cohesive, unified appeal. The days of damages experts presenting rote spiels that are uncoupled from the case engine need to end. John Blumberg, an apparent advocate of the Reptile, in his recent article in this magazine, brings out that each case must simply and succinctly present its “theme” with stories and analogies. (J. Blumberg, Expert Testimony that Persuades, Advocate, (6/2014) p. 99.) This helps the jurors identify with the injured person. As jurors are led step by step through the expert’s methodology, it is vital that the examination creates immediate interest. For example, Blumberg proposes that attention-getting statements be made that set up the vocational economic expert’s testimony, such as, “Dr. Jones, I am going to ask you to project to a reasonable degree of economic certainty how much Ms. Thomas’ future economic damages are likely to be.” The natural follow-up question is – “Are you qualified to do this for us?”

After the expert answers, “Yes,” the jury is now engaged in listening intently to the expert’s qualifications to see whether or not they agree. Blumberg notes that these “news headline” set-ups can effectively preface the expert’s testimony in each of the various damages areas. Finally, Blumberg cautions against juror overload by advocating the rule of three, where three points at a time are made, which are then backed up with stories and analogies.

Undoubtedly, Ball and Keenan provide readily transferable insights that can be utilized not only by the attorney, but by the retained experts. Equipping the damages experts begins and ends with the law. Compensation is to be provided for all proven harms and losses, both tangible and intangible. It is the law. A vocational economic expert will clearly spell out the step-by-step process involved in performing a vocational assessment, and then follow that up with how the actual line-upon-line evaluation was conducted with regard to the injured client. Reptiles are razor sharp observers.

Ball and Keenan stress that the proportion of time spent on harms, losses and money needs to be equal to that spent on liability. This means that rather than getting damages experts on and off the stand with expediency, it is vital to judiciously and thoroughly walk through their conclusions in order to fully inform the Reptile. But this can only be done if the attorney ensures that the expert is mindful of the boredom the Reptile feels when the law is disconnected from the damages presentation.

For example, the jury is introduced to the preponderance standard that maintains that damages must be proved on a more likely than not basis. Usually, the expert is asked one question at the end of their testimony as to whether the damages are more likely necessary, than not. Ball and Keenan stress that by not repeatedly reiterating this lawful standard, jurors can and do revert to the unlawful basis of “reasonable doubt.” Thus, in order for jurors to balance the scales between harm and damages, the Reptile must be instilled with the lawful standard that it is more likely than not that the client’s injuries have led to her losses. Repetition is vital to keeping the Reptile focused on the law.

Moreover, it is often the case that the vocational expert is uniquely positioned to describe the client’s lifestyle losses after the collision, in comparison with before it, including reduced mobility and overall functional capacity. This ties back to other significant losses seen in their being a displaced worker and provider.

Ball and Keenan state that other proven intangible losses might include loss of self-esteem gained from working, relationships on the job, significance in contributing to the greater good, role within the family circle, physical wherewithal and confidence, mental discipline, and emotional fortitude. Many clients feel humiliated, isolated, unprotected, looked down upon, and angry at being left with a permanent need for medical intervention. In contrast, the Reptile also spots the indolent, non-engaged survival instincts of others.

Reptiles become alert when they hear personal stories. Therefore, during the vocational interview, the client’s story is drawn out: “Tell me how this has impacted your life?” The vocational expert will listen as the client discloses her heart. As pauses arise, the client is invited, “Please, tell me more about that.” As the client is vulnerable and transparent, the vocational consultant can list their tangible and intangible harms and losses. This helps the Reptile to appreciate the scope and extent of the damages as they balance the scales with fair compensation.

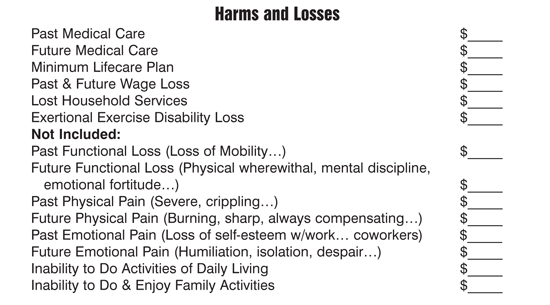

It is vital that the vocational expert refrain from overcomplicating the damages presentation, and thereby fail to equip the jurors’ Reptiles for their deliberations. Ball and Keenan say that this can simply and succinctly be done by depicting the harms and losses in short, clear sentences. For example, “John is no longer able to work as a carpenter.” “John is severely limited physically.” “John is unable to work full-time,” etc. The point is that core phrases can be written down and remembered by the Reptile, who needs things to be simple. Ball and Keenan state that other short statements need emphasizing, such as, “Pain is the worst harm in the case”; “No deduction for any outside reason”; and “This type of loss can happen to any of us.”

The vocational expert can list out the Harms and Losses in a readily understandable format.

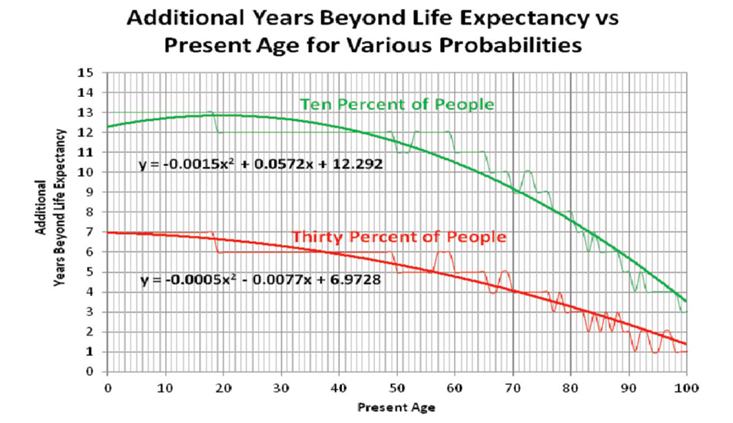

Ball and Keenan put forth that the vocational expert can explain other important damage elements such as worklife and life expectancy estimates. Because workers are staying longer in the workforce, and people are living longer, injured plaintiffs have the “right to be taken care of without worrying about running out of money.” The Reptile is concerned with the dangers of running out of money.

Ball asserts that the client has the right to hope for a long life, and the right to have the money necessary should that occur. Most of us are “not likely to die right on schedule.” From the graph in Figure 2, a 65-year old man who goes on to reach his projected life expectancy still has a 30 percent chance of living four and one-half more years, and a 10 percent chance of living 10 more years.

Prevailing law states that a tort victim’s recovery may be for losses extending to the balance of their life expectancy, undiminished by any shortening of that expectancy as a result of the injury. (Overly v. Ingalls Shipbuilding, Inc. (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 164, 174.)

Ball and Keenan maintain that the Reptile needs a simple, understandable damages presentation that prepares it for deliberations. Connecting the law to the client’s story wakes the Reptile, but helping it to reason through the two-sided viewpoints, is essential to equipping it for its needed decision-making. This can equally be done by both plaintiff and defense attorneys and experts. It is all about the law. Both sides want a lawful resolution, or else the Reptile will spy them out.

Ball and Keenan conclude the law is paramount in that “when a driver gets behind the wheel, she implicitly agrees – in advance – to be responsible for any harm she does if she violates any safety rules.” But as Ball and Keenan also admit, “The Reptile is not particularly concerned with your client…the Reptile is concerned with the Reptile (their own safety), their world and family, their survival, and little else.” Therefore, if the jurors’ Reptiles are not aroused to the unlawful harms and losses, then they will not be alert to balance those out.

Like in my son Mark’s wrongful death, drivers violate the law and their agreed-upon covenant when they travel at an unsafe speed, fail to watch where they are going, and drive while intoxicated. It is the job of the jurors to ensure that the scales of justice balance, even with such intangible damages as my grandson, Odon, never again having his father, or other brothers and sisters, or our having additional grandchildren, and great grandchildren. When the law is broken, it is the Reptile that balances the harms with full and fair compensation, with no outside reasons.

David Orlowski

David Orlowski DMIN CRE has worked as a vocational economic consultant for 27 years. He has previously served as President of the American Rehabilitation Economics Association. Dworlowski@aol.com 602.549.0979

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine