A house for equal justice, from design to completion

A historical look at Los Angeles County’s Stanley Mosk Courthouse and its architect, Paul R. Williams, an African-American and one of the premier architects of his day

Twenty-six years. That’s how long Los Angeles lacked a downtown courthouse.

Just before 6:00 p.m. on March 10, 1933, the Long Beach earthquake struck Southern California. The 6.4 magnitude temblor killed 120 people and remains California’s second-deadliest earthquake. It caused widespread structural failure of unreinforced brick buildings.

Downtown Los Angeles suffered little devastation compared to the southeast area of the county. A notable exception was the Los Angeles County Court House. The building, called the Red Sandstone Court House because of its exterior masonry, sustained such heavy damage that it could no longer be used. Constructed in 1888, and opened in 1891, the grand County Court House was located at Temple and Broadway. It was the County’s third courthouse, but first true courthouse, as the previous two buildings had been converted from other uses.

Even before the Long Beach earthquake, however, the courthouse, once called the “jewel of Los Angeles,” was dramatically and rapidly deteriorating. On February 10, 1932, the County’s Chief Mechanical Engineer, William Davidson, reported to Supervisor J. Don Mahaffey that a section of stone had broken off of the courthouse’s clock tower, and crashed through the roof of Judge Joseph Sproul’s office. Fortunately, as the accident had occurred at 6:25 a.m., no one was hurt. Davidson also recounted that the previous heavy earthquake had affected several tons of the building’s ornamentation. As remedial safety measures, the County had removed 12 tons of rock and anchored the outside of the building.

Despite this, the masonry structure was so compromised that Davidson recommended removing the clock tower. The Board approved and immediately implemented the recommendation. Within a few weeks the clock tower and other ornamentation were removed, in a move called a “clock-ectomy,” and a new roof was installed.

This structural modification was not, however, sufficient. In early April 1932, just a few moments before Superior Judge Lewis Howell Smith was to take the bench in Department 9, a heavy glass skylight fell from the ceiling, and shattered onto the counsel table and chairs. Fortunately, no one was at the counsel table. This incident spurred members of the public to urge the Board of Supervisors to replace the dangerous, deteriorating courthouse.

Within a year, the Long Beach earthquake dealt the courthouse its final blow. Dismantling the building was such a large undertaking that the County asked for federal funds to finance the task. Demolition of the structure was not completed until 1936.

Making it do

For the next 25 years, Superior and Municipal judges used facilities at multiple locations downtown, including the old Hall of Records, Los Angeles City Hall, Hall of Justice, Brunswig Building (513 North Main), Patriotic Hall (18th and Figueroa), the Lincoln Heights Jail court, the State Building, and the old Municipal Court Building.

Judges, the bar, jurors, litigants, and the public patiently endured these makeshift accommodations for two and a half decades, from the dawn of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s first term to the twilight of President Dwight David Eisenhower’s last term. Meanwhile, Los Angeles experienced unforeseen population growth. When the Red Sandstone Court House opened in 1891, the population of Los Angeles County was 108,336. When it closed in 1933, the County’s population was 2,380,870.

This growth placed even more pressure on the County to provide a permanent solution to the court “housing crisis.” A decade without a courthouse was enough. In 1944, the Board of Supervisors was determined to build a courthouse as soon as possible. A Court House Committee was formed to study the issue and was tasked with estimating the needs of the Court’s Metropolitan Civil Departments for the next 30 years.

Serving the public

The Committee estimated that the County’s population would increase 50 percent over the next 25 years, up to around 5,250,000 by 1970, and noted, “Experience in the past two years shows these estimates are most likely ultra-conservative.”

The unanticipated population explosion, coupled with a lack of a permanent courthouse, created a court emergency. In 1945, the Chief Justice assigned judges from outside of the county to help carry Los Angeles’ workload. In 1946, five judges from other counties sat as regular working members of the Los Angeles County Superior Court. The Court also relied on commissioners and lawyers serving as judges pro tem.

Adding judicial officers did not, however, correct the problem, so in early 1946 the Presiding Judge ordered the Sheriff to utilize emergency powers to provide additional courtrooms. Temporary wartime bungalows used as dormitories by the U.S.O. were quickly converted to house the Probate Department.

These measures, too, were insufficient. The number of cases set for trial increased over 50 percent from January 1, 1946 to November 1, 1946, and by the end of that year hearings were set 10 months out.

After the war, the County purchased land for a new courthouse, at the intersection of Grand Avenue and Temple Street. The courthouse construction did not come to fruition, however, for several reasons. A 1946 court construction bond measure failed, essentially slowing momentum to a stop for several years. Labor strikes and, later, a steel shortage occasioned by the Korean War, contributed to the delay. There was no consensus on whether there should be separate Municipal Court and Superior Court buildings (the original intent), or a single building to house both courts.

Moreover, despite the clear need for a permanent courthouse, the proposed site was not greeted with enthusiasm. At the time, it was estimated that 75 percent of the attorneys in the county were based in the downtown area. Attorneys circulated fliers indicating that they were “100-1” against what was called the Grand and Temple site.

Some of the controversy was due to the perception that the site was inconvenient. Many lawyers argued that a more appropriate location was the area of Spring and Broadway, between Second and Third Streets. There, a new courthouse would be closer to the downtown law offices.

In addition, the suitability of the site itself was questioned. There was, literally, an 80-foot-tall hill on Hill Street. Bunker Hill and the proposed courthouse site would require considerable, costly grading.

Paul Revere (Williams) rides again

In 1951, the County Board of Supervisors appointed architects John C. Austin, Paul R. Williams, J.E. (Jess) Stanton, Adrian Wilson, and the firm Austin, Field & Fry to design a “combined courts building.” The County awarded the construction contract to the low bidder, Gust K. Newberg Construction Company.

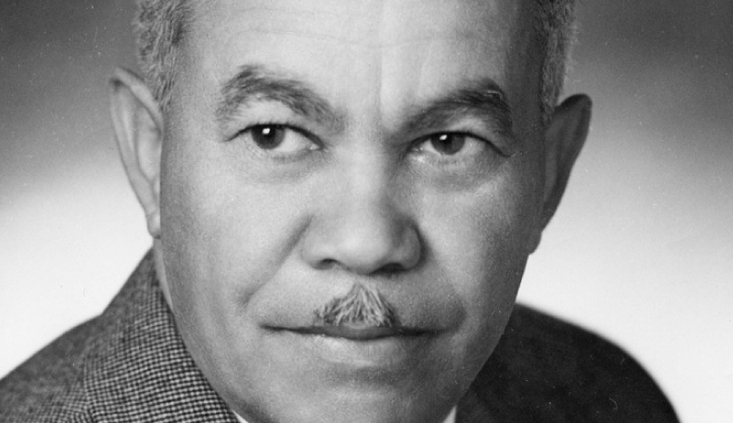

The “Allied Architects,” as they called themselves, were highly regarded and brought decades of experience in designing public and private, residential and commercial, small- and large-scale projects. One of them, Paul Revere Williams, had by then built a 30-year, well-deserved reputation for excellence and hard work, and was considered one of Los Angeles’ very finest architects.

Paul Revere Williams was born in Los Angeles on February 18, 1894, to Chester Stanley Williams, Sr., and Lila Williams, who had recently relocated from Memphis, Tennessee. Tragically, Williams lost both parents by the age of four, and he and his older brother, Chester Jr., were placed in separate foster homes.

Despite this, 1890s Los Angeles was a vibrant, multi-ethnic environment, in which young Williams thrived. In elementary school, Williams was known as the class artist, and he spent endless hours drawing. Williams enrolled in architecture classes in high school. There, an advisor questioned Williams’ choice in pursuing a career in architecture. Williams recalled later that he had responded, “I had heard of only one Negro architect in America [Booker T. Washington’s son-in-law, William S. Pittman] and I was sure this country could use at least one or two more.” (Paul R. Williams, “If I Were Young Today,” Ebony, August 1963, p. 56.)

Williams later cited this challenge as deciding his future. Architecture was no longer an assumed profession borne of a love of drawing. It came, instead, to be a well-thought-out commitment, to be assiduously pursued.

Williams pursued an architectural education at the Los Angeles School of Art and the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, and also sought employment at Los Angeles’ leading architectural firms. At only 20, he won a noted design award, and as he continued to excel in other competitions, other architects took notice. In 1916, Williams was hired by noted architect Reginald D. Johnson. Williams won another architectural competition, and his winning drawings were published in a trade publication.

In 1919 Williams was hired by another prominent Los Angeles architect, John C. Austin (Williams’ future collaborator on the County Courthouse project). Austin’s architectural firm provided Williams with valuable experience. As the firm was commercially-oriented, it allowed Williams to design large-scale projects, and to use a wider range of architectural styles.

Williams obtained his architect’s license in 1921, struck out on his own in 1922, and became the first black member of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1923. Williams earned a reputation for never settling for less than perfection in his work, and for dignity in his relationships with clients and colleagues. He worked constantly, on a wide range of projects. One of his earlier solo projects, the 28th Street YMCA (1926), is on the National Park Services’ National Register of Historic Places, and is a City of Los Angeles’ Historical-Cultural Monument.

Although very successful, Williams remained mindful that he had to overcome racial prejudice, so he had to “devote as much thought and ingenuity to winning an adequate first hearing as to the execution of the detailed drawings.” (Paul R. Williams, “I Am a Negro,” The American Magazine, July 1937, p. 162.) For example, Williams spent hours learning to draw upside-down, so that a prospective client could be seated on the opposite side of the table, to become engrossed in the drawing and to lose focus on Williams’s skin.

Williams later wrote that in these early years, he was determined to “force white people to consider me as an individual rather than as a member of a race,” and that “Occasionally, I encountered irreconcilables who simply refused to give me a hearing, but, on the whole, I have been treated with an amazing fairness.” (Ibid.) Williams also observed that he did not regret the difficulties, because, “I think that I am a far better craftsman today than I would be had my course been free.” (Id. p. 161.)

The project that propelled Williams into the category of elite architects was Cordhaven, the Beverly Hills estate Williams designed in 1933 for automobile magnate E.L. Cord. Although Cord lacked formal higher education, he knew and appreciated quality of workmanship and design.

Williams later recounted that when Cord telephoned him, and asked to meet immediately at a site in Beverly Hills to discuss building a new home, Williams tried to defer the appointment to the following day. Because Cord insisted, they met later that day at the site. Cord told Williams that he had already discussed plans with a number of other architects, and demanded to know how soon Williams could submit preliminary drawings.

Sensing that Cord valued prompt action, Williams answered, “By four o’clock tomorrow afternoon.” Cord said that it was impossible, as every other architect had asked for two or three weeks, but he gave Williams the go-ahead. Williams delivered the preliminary plans by the scheduled hour. He did not tell Cord that he had worked for 22 hours, without sleeping or eating. (Williams, “I Am a Negro,” p. 162.) Williams was hired, and created Cordhaven, a 32,000 square-foot home with 16 bedrooms and 22 bathrooms.

By the time of the Los Angeles County Courthouse project two decades later, Williams’ portfolio included noted residential, commercial and public buildings. Williams was involved with approximately 3,000 projects over his career, which spanned from the 1920s through the 1970s. Williams’ vision shaped the growth and look of Los Angeles. Above all, Williams wanted to be judged as an individual, through courage and honest effort.

The architects design “A proper building”

Paul R. Williams believed that public buildings should be conservative in design and used that principle when designing the Los Angeles County Courthouse. At the outset of the design phase, the architects pledged to the Board of Supervisors to do their “utmost to design a proper building as to plan and purpose; simple and direct in plan, utilitarian and functional in design, of appropriate materials for long life, and at as modest a cost as practical – the architectural style to be in keeping with the latest aesthetic thinking with due consideration of its environment, the climatic conditions, its own purpose and in harmonious keeping in materials and color with other buildings of the Los Angeles Civic Center.”

When the architects submitted the preliminary plans in October 1952, they described the courthouse’s design as a “conservative version of contemporary architecture.” The approaches and entrances were designed in “a manner expressing the dignity requisite in a courthouse, the principal embellishment consisting of symbolic structure.”

The “symbolic embellishment” that ultimately graced the Grand Avenue and Hill Street elevations of the County Courthouse consists of terra cotta creations by two noted artists. Donal Hood designed the “Justice” sculpture on the Hill Street facade. Albert Stewart created the three “Foundations of the Law” figures on the Grand Avenue side, to represent the legal traditions upon which America was founded. The terra cotta work was manufactured by Gladding McBean at its Lincoln, California, factory.

Ground broke on March 26, 1954, at the once-controversial site. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren was the honored guest at the ceremony, which was also attended by Supervisor Kenneth Hahn and his three-year-old son “Jimmy,” now Judge James Hahn. The formidable grading and excavation project commenced and, ultimately, the 80-foot hill was leveled for construction. The actual construction of the building began in 1956.

The judges, most of whom had never presided over a courtroom in a permanent courthouse, took an active role in the design of the new building. Many of their changes, such as to the configuration and layout of chambers and jury facilities, were incorporated into the final plans. Perhaps frustrated by the pace of the process, judges also successfully demanded that a mock courtroom be built, so they and their staff could test how well the proposed courtrooms actually functioned. A full-scale, prototype courtroom was constructed inside of the Hall of Records, at a cost of over $30,000.

Still other changes were on the way. Early in the design phase it was decided that there would be a single building, for the Superior Court and Municipal Court. The Superior Court clerks requested roll-top desks. Judges also insisted on cold water fountains in each courtroom, for the benefit of the public. Despite the high cost ($1,241.67 per unit), the water fountains were installed.

Other changes occurred over time, after the courthouse opened. It had initially been anticipated that 80 percent of the visitors would pass through the First Street entrance. Therefore, that entrance was designed to be the courthouse’s main entrance. It led into what was then designated as the first floor (now the second floor), with the floor below it (now the first floor) designated as the ground floor.

The building was expected to have a life of 50 to 75 years, but upon its completion, the architects publicly stated that they had designed the building to last 250 years.

Quarter-century wait ends

When the $24 million Los Angeles County Courthouse was dedicated on October 31, 1958, it was hailed as the most important building constructed in California in the previous 50 years. It opened for public business at 9:00 a.m. on January 5, 1959.

At 850,000 square feet, it was (and remains) the largest courthouse in the United States. Inside were 110 courtrooms, allocated 60/40 for Superior and Municipal Court. The entrances featured mosaic tile columns, and marble floors that were quarried in Italy and polished in Vermont. Eastern White Oak panels graced each courtroom.

The courthouse also contained eight large courtrooms, with prominent slabs of Tennessee Rosemont marble on the wall behind each bench. These courtrooms would include the Presiding Judge’s courtroom and chambers; and the headquarters of the various court departments, such as “Master Calendar,” “Domestic Relations,” and Probate. Because the courthouse was, after all, located in Los Angeles County, the other large courtrooms were to accommodate what we now call “high profile” cases. The paternity trials of Charlie Chaplin in the 1940s were widely (and often sensationally) reported by the press. Therefore, the architects were specifically asked to include large courtrooms “to be used in cases where there is a large public interest.”

Modern functional elements included full air conditioning throughout the building; and fire-retardant, fiberglass-backed burlap on the back wall of each courtroom, to serve as acoustical paneling. Underground tunnels connected the courthouse to other civic center buildings, and remain in use today.

Fulfillment of principles of justice

The forward-thinking architects, engineers, and members of the Board of Supervisors were correct. Now, more than half a century after the County Courthouse’s dedication, the controversies over the site, the 80-foot-tall hill, and construction delays, have all essentially been forgotten.

Supervisor Kenneth Hahn noted that the courthouse was for all to receive a fair trial and equal justice. If the courthouse did not perform or satisfy the basic American need for liberty and freedom, Supervisor Hahn said, it would be worthless, as what goes on inside the building is more important than the building itself. A free and independent judiciary, he said, is needed for America to continue to be the “land of the free and the home of the brave.”

This article originally ran in “Gavel to Gavel” in Spring 2013.

Elizabeth R. Feffer

Judge Elizabeth Feffer served on the Los Angeles Superior Court for 13 years, presiding over more than 75 civil jury trials, more than 500 civil bench trials, hundreds of evidentiary hearings, and numerous settlement conferences. Now a mediator, arbitrator, referee, and private judge with ADR Services, Inc., Judge Feffer handles a diverse range of complex cases.

Endnote

Sources and Acknowledgements

The Paul Revere Williams Project, at the Art Museum at the University of Memphis.

Los Angeles Superior Court Planning and Research Unit.

Hudson, Karen E. (with David Gebbard), Paul R. Williams, Architect (1993).

Williams, Paul R., “I Am a Negro,” The American Magazine, Vol. CXXIV, No. 1, July 1937, p. 59.

Williams, Paul R., “If I Were Young Today,” Ebony, Vol. XVIII, August 1963, p. 56.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine