The expert witnesses for your premises-liability case

Finding the right expert for a specific type of case

Your phone rings. A potential client fell down on steps, seriously injuring herself. She thinks the steps may have been uneven, they may have been slippery, and the area was poorly lit. If you decide to take this case, will you need an expert to prove liability? Most likely, yes.

Much has been written in Advocate regarding experts and premise liability. This article is narrowly focused to help you select the correct causation expert for your case.

At the outset of this journey the first question you must answer is what specific information do you want the expert to share with the jury? When trying to answer this question, begin by reviewing the jury instructions. CACI Nos. 1000 (Premises Liability-Essential Factual Elements), 1001 (Basic Duty of Care), 1002 (Extent of Control Over Premises Area), and 1003 (Unsafe Conditions), which provide the foundation for premises-liability cases. If your case involves a rented-premise situation, review CACI No. 1006 (Landlord’s Duty). Similarly, if your case involves an independent-contractor scenario, review CACI No. 1009 (Liability to Employees of Independent Contractors for Unsafe Conditions).

Be sure to read the entire set of instructions before deciding which instruction or instructions may be applicable to your set of facts. Determine the duty owed by the defendant to your client. The jury instructions will give your case shape, and hopefully help you understand the contours of the causation you will have to prove.

An expert needs to provide something helpful to the case with his or her expert testimony. What is that something special? This is a conceptual exercise, but also the requirement set forth in California Evidence Code section 801, which allows expert opinions that are “[r]elated to a subject that is sufficiently beyond common experience that the opinion of an expert would assist the trier of fact.” The expert can offer an opinion on an ultimate issue to be determined by the trier of fact. (Evid. Code, § 805 [“Testimony in the form of an opinion that is otherwise admissible is not objectionable because it embraces the ultimate issue to be decided by the trier of fact”].) Imbued with power from the Evidence Code, your expert has the unique ability in the case to tell the jury what to think and why. He or she can be the queen on your chessboard.

Common categories of experts in premises liability cases

So what kind of experts will help you prove your case?

For a practitioner new to this area of law, this is a tough question. A good place to help identify the types of experts that are used in your type of case is O’Brien’s Evaluator, or a similar such publication. O’Brien’s indexes cases (mostly from Southern California) by expert used, injury type, and area of law. Entries also include the parties, a brief synopsis of the case, the settlement amount, and the names and titles of the experts who testified in the case. Similar resources include CAALA’s Trialsmith or VerdictSearch searches. Westlaw offers a directory of experts, as well as the book Lawyers Desk Reference 8th Edition, published by Clark Boardman Callaghan. Do not underestimate the value of CAALA’s listserv, which also provides a great place to find answers.

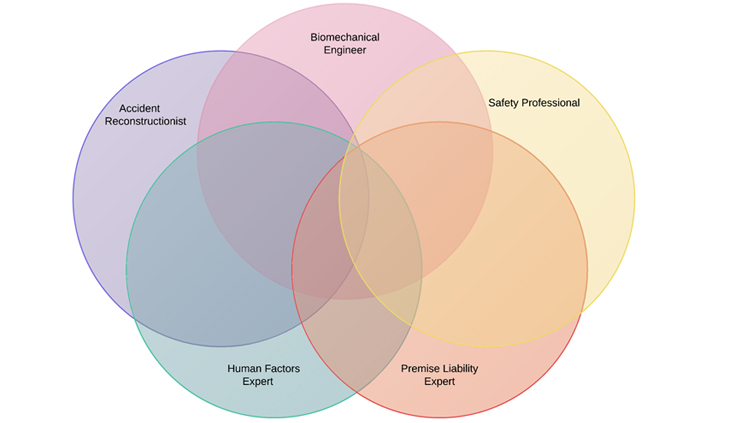

Assuming you glance through one of these resources, you find a variety of different kinds of experts. But what exactly is a Biomechanical Engineer versus a Human Factors Expert versus a Safety Professional? What is an Accident Reconstructionist? When would you want a Property Management Expert? Some of these designations overlap, and sometimes different kinds of experts can testify to the same facts, but for different reasons. This overlap is visually illustrated in the following Venn diagram. The remainder of this article delves into these expert designations.

• Biomechanical engineer

A biomechanical expert can testify about physical forces acting on a human body. For example, your potential client claimed to have ridden on a wooden toboggan that broke on her first trip down a hill and caused a splinter of wood to impale her back. But she took one more ride down the hill before she recognized she was injured. (See e.g., 46 Am. Jur. Trials 631 (1993) The Use of Biomechanical Experts in Product Liability Litigation, p. 639.) Were you to represent that client and bring this case to trial, you can be sure defense counsel would introduce testimony from a biomechanical engineering expert establishing that, if the plaintiff were telling the truth, then the placement of the fragment of wood in the plaintiff’s body defied the laws of physics. This is the type of testimony that a biomechanical engineer can supply − the physical force (a shard of wood) − acting on a body (the plaintiff’s back). (Id. at § 1.) As this illustration shows, engaging an expert can help you in your case selection as much as in winning your trial.

There are caveats. A biomechanical engineer is not medically trained and can-not give medical testimony. A biomechanical engineer is simply engaged in “the study of forces acting upon and the motion of the human body. The study of biomechanics is concerned with the response of living matter to forces.” (Id. at p. 639.)

Montag v. Board of Education (1983) 112 Ill.App.3d 1039 presents another example of the kind of testimony a biomechanical engineer can provide. In Montag, the plaintiff fell while participating in the school gymnastic team’s practice. A biomechanical engineer testified that no combination of existing safety mats could have prevented the high school gymnast’s injury. Although the testimony discusses physical injury, the expert testimony is not medical per se. Rather, its focus is on the variety of forces acting on a body.

• Human factors

The field of human factors, or human factors and ergonomics, as it is often referred to, is broad. Practitioners often work in the field of designing new products, or making old products safer and easier to use. A human factors expert may have an undergraduate degree in a field such as engineering, psychology, design or physiology, as well as a graduate degree in human factors or a related field. There are both Ph.D. and M.S. degrees available in the field of human factors.

Selecting your human factors expert depends upon, and should be tailored to, the type of evidence being reviewed. (40 Am. Jur. Trials 629 (1990), Using the Human Factors Expert in Civil Litigation.) If causation involves or depends upon the curve of a ramp, then you would want a Human Factors expert with a background in engineering. But if you wanted the expert to discuss what details are recognized by the average person while driving up a ramp, you would probably want a human factors expert with a psychology background.

Bacile v. Parish of Jefferson (4th Cir. 1981) 411 So. 2d 1088, provides an example of the kind of trial testimony you can expect from a Human Factors expert. There, the expert opined that the storm grate commissioned by a city parish was dangerously designed because a child’s foot could slip through and the child could be injured. The expert further opined that the 2.5-inch opening presented an unsafe condition, with no consideration given for human frailties. He further testified that the grate was located in a subdivision where people are walking and that it is conceivable and probable that persons would step through the opening and sustain an injury. Finally, the expert testified special design considerations should be given to the human factor that someone could step through the opening.

• Safety expert

A safety expert, or safety professional, is a term that encompasses many different backgrounds. There is a national certification, a CSP certificate that stands for Certified Safety Professionals. (See http://www.bcsp.org/CSP.) According to the Board of Certified Safety Professionals (CSP), its members are people who perform at least 50 percent of professional-level safety duties, including making worksite assessments to determine risks, assessing potential hazards and controls, evaluating risks and hazard control measures, investigating incidents, maintaining and evaluating incident and loss records, and preparing emergency response plans. Other duties could include hazard recognition, fire protection, regulatory compliance, health hazard control, ergonomics, hazardous materials management, environmental protection, training, accident and incident, investigations, advising management, record keeping, emergency response, managing safety programs, product safety and/or security.

For example, a certified safety professional may have been a “safetyman” on construction sites for many years. A “safetyman” is in charge of making sure a worksite meets OSHA standards, prepares the safety manual, and brings the safety of the construction site up to industry standards. Other CSPs may have an undergraduate degree in engineering, and an advanced degree with a safety emphasis. Based on the CSP’s background, he or she may be able to give an opinion on the maintenance required for a stairway, list the code sections that are applicable to the premises, and possibly discuss why aspects of design are important (for instance, why steps should all conform to the same size and height and width). The CSP may also be able to provide information regarding safety policies that were in place at the premises, whether those policies were satisfied, and what, if any, the safety standard prevails in the trade.

Safety engineering is defined by the Code of Regulations:

Safety engineering is that branch of professional engineering which requires such education and experience as is necessary to understand the engineering principles essential to the identification, elimination and control of hazards to people and property; and requires the ability to apply this knowledge to the development, analysis, production, construction, testing, and utilization of systems, products, procedures and standards in order to eliminate or optimally control hazards. The above definition of safety engineering shall not be construed to permit the practice of civil, electrical, or mechanical engineering.

(Cal. Code of Regs., tit. 16, § 404(ll); see also Avrit and Fink, The Use of Experts in the Premise-Liability Case (March 1, 2014) The Advocate.)

• Tribologists

Perhaps your case would be assisted by testimony from a tribologist, an expert in the study of interactions of sliding surfaces. When might this be useful? When you need to show that a surface was slippery, and caused your client to fall. Tribologists can testify about friction, wear, and lubrication of a surface. A tribometer is a mechanical device used to measure floor slip resistance and risk. (Brault, John, It’s Gotta Be the Shoes (March 1, 2008) Advocate.) It can be used with a test foot made from the shoe’s soling material at the site of the slip-and-fall. If a tribologist’s testimony is crucial to your case, you may consider hiring a certified tribologist.

• Retail industry experts

If you need to show that the standard of care was not met for cleaning up spills in a grocery store, the way product is stacked on a retail floor, or the operation of a forklift with customers present in a lumber yard, then you will need an expert with a background in retailing. While the testimony as to safe versus unsafe practices may seem similar to that of a safety expert, this expert must have the background to relate what should really be expected of the retail establishment based on custom and practice.

• Accident reconstructionists and property management experts

Two more types of experts that may be helpful are an accident reconstructionist and a property management expert. The accident reconstructionist can be useful when the parties cannot agree on how the accident or incident actually occurred. The property management expert can testify about the standard safety measures and practices in property management.

Selecting the right kind of expert(s) for your case

Let’s apply this discussion to the hypothetical at the beginning of this article (i.e., prospective client fell down stairs, thinks the steps were uneven and possibly slippery, the area was poorly lit, and client has a serious injury). First, determine the appropriate jury instruction(s) that will apply to the case. Then think about what information you want the expert to bring to the jury.

A biomechanical engineer could testify about the step of a person, recognition of a pattern in steps, how staircases are engineered for a person’s foot, and the forces that cause unbalance when a person’s foot falls in an unexpected place. The biomechanical engineer could also speak to the coefficient of friction and the forces that cause a person to slip.

A human factors expert with a psychology background could give insight about how most people descend and ascend a staircase. He or she could possibly opine on what environmental factors are cognitively recognized by a person walking, and which ones aren’t, and why the uneven stairs in this case are particularly dangerous for your client, especially if poorly lit.

A certified safety professional could testify to what the standard staircase should be, how they should be lit, what the applicable code sections are, and why the uneven steps are considered unsafe. The safety professional could also possibly address how often stairs are to be inspected and cleaned. You may even want a certified tribologist to address the “slippery” factor.

An accident reconstructionist could explain the directions of different forces and how they unfolded, i.e., X angle of stair caused foot Y to travel in this direction with force Z ending in twisted ankle at location A. The addition of substance B to the stair surface instigated the fall.

And finally, a property management expert could explain that the standard of care for similar such properties require even, clean steps with adequate lighting. They may even be able to cite the applicable building code sections.

The Venn diagram shows how the testimony you might receive from an expert may extensively overlap with other kinds of experts, so selecting the “right” expert is often not simple. On the upside, you have many options and experts at your disposal. Think hard about what information the jury needs to be able to return a verdict in your client’s favor. That inquiry will help you narrow your options. Also keep in mind the actual demarcation of an expert’s areas of expertise depends on the individual expert, and his or her background and training.

Comparing and choosing the “best” expert(s) for your case

Other Advocate articles have offered in-depth suggestions for selecting an expert. Here are some additional thoughts that may help you choose not merely the “best” expert, but the one that will help you win your case.

Preliminarily, you must determine if the prospective expert has a conflict of interest representing your client against the defendants. You should also review the expert’s Curriculum Vitae or resume, with an eye for degrees, publications, society memberships, and job positions in the field. Don’t automatically select the expert with the longest or most impressive resume. For a garden-variety slip and fall, having an expert in the area who has time, and gives you personal attention, may be more beneficial than an expert who has a long pedigree but is short on patience.

However, if your case boils down to a “battle of the experts,” the weight of your expert’s opinion may be determined by your expert’s resume. When it is a battle of resumes, immerse yourself in that expert’s field for a moment. What are the most prestigious journals, and has your expert published in those? Recently? Is there an appointment at an academic institution? How many years of applicable experience does your expert have? Has the expert testified before? Did the jury respond favorably to the expert?

Do not underestimate the importance of your “gut check.” Do you feel good about presenting the individual to the jurors and asking them to believe him or her? Does your expert’s background seem like it would be appropriate for a person testifying in front of a jury regarding the chosen subject area? Make sure the expert’s area of expertise is not so specific that it excludes your issues.

An important step for choosing a professional expert, or expert that testifies often, is to determine what his or her reputation is among judges and attorneys. Credible? Hired gun? Look at previous transcripts and see if the testimony seems consistent between cases. Has the expert ever stated things that would be detrimental to your case? Does the expert represent both plaintiff and defendants? A professional expert is not a bad thing, but do your due diligence and make sure that the expert you choose is the best for your set of facts.

And finally, don’t put friends or relatives on the expert short list. The connection will translate to bias in the jurors’ minds, possibly undermining even the best testimony. Narrow the expert pool to a few potential experts and call them. Run your set of facts by him or her, see what each expert thinks, and gauge how comfortable you are working with each individual. Then select the winner!

Once you have embarked on a relationship with your expert, you want to share with him or her information that is specifically tailored to his or her needs. Most experts will be very comfortable articulating what type of discovery you should draft, how to formulate your demand to inspect the premises, and what type of individuals you should designate as “persons most qualified.” (David Reinard, More Effective Use of Experts in Premise Liability Cases: the right expert will help you better prepare for your case and win at trial (March 2012) Advocate.) Chances are the expert will have dealt with more slip and fall cases than you have, and will have a good feel for what types of information are crucial.

In conclusion, finding an expert for your premise liability case may seem daunting, but once you get a handle on the terminology, it becomes a lot less overwhelming. And when you do retain the right expert, you will find that he or she is a wonderful and powerful resource throughout all stages of the litigation!

Elizabeth McElwee Janss

Elizabeth McElwee Janss, Esq. is a solo practitioner in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles. She has a master’s degree in Neuroscience and a bachelor’s degree in the Biological Basis of Behavior from the University of Pennsylvania. She graduated from UC Hastings College of the Law in 2002, and handles a variety of case types including elder abuse, personal injury, and wrongful death.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine