Ups and downs of stairway cases

Overview of the primary laws involved in stairway-fall lawsuits

Stairways are among the most dangerous elements one will encounter in our environment. Often involving a vertical drop of over eight feet, the forces a human body acquires during a stair fall are substantial. Each year, falls account for millions of trips to the emergency room, numerous deaths, and countless permanent injuries. There is good reason why the Uniform Building Code and ADA technical guidelines pay so much attention to stair design and materials. Stairways literally can kill. It has been said that the Led Zeppelin song “Stairway to Heaven” was really a protest song against the dangers of stairways the band recognized in the 1970’s.

This article gives a general overview of the primary laws involved in stairway fall lawsuits, with examples of how to accurately document and effectively communicate to jurors some of the technical code violations and safety problems that commonly exist on stairways, and how to communicate the safety measures that would make the stairway safe.

General legal overview

Stairway lawsuits sound in negligence. As a general rule, “[e]very one is responsible, not only for the result of his willful acts, but also for an injury occasioned to another by his want of ordinary care or skill in the management of his or her property or person, except so far as the latter has, willfully or by want of ordinary care, brought the injury upon himself.” (Civ. Code, § 1714(a).) A landowner owes a duty to exercise reasonable care to maintain his or her property in such a manner as to avoid exposing others to an unreasonable risk of injury. (Alcaraz v. Vece (1997) 14 Cal.4th 1149, 1156; Scott v. Chevron U.S.A. (1992) 5 Cal.App.4th 510, 515.) The general rule of property owner liability is set forth in Sprecher v. Adamson Companies (1981) 30 Cal.3d 358, 368, which states that a landowner has a “duty to take affirmative action for the protection of individuals coming upon the land . . . .” This duty arises because ownership of land includes the right to control and manage the premises. The landowner’s “mere possession with its attendant right to control conditions on the premises is a sufficient basis for the imposition of an affirmative duty to act.” (Id. at p. 370.) The right to control the premises lies at “‘the very heart of the ascription of tortious responsibility’” in premises-liability actions. (Id. at p. 369.)

The CACI jury instructions in stairway premises cases are at the 400 series and 1000 series, with particular focus on the 1000 series. In a landlord/tenant case, or a case involving an injury to a third party from a dangerous condition on leased property, do not overlook CACI 1006, which includes strong language about a landlord’s affirmative duty to inspect property, even where a tenant is in possession. For example, one of the cases underlying a landlord’s affirmative duty reflected in CACI 1006 states: “a commercial landowner cannot totally abrogate its landowner responsibilities merely by signing a lease. As the owner of property, a lessor out of possession must exercise due care and must act reasonably toward the tenant as well as to unknown third persons. At the time the lease is executed and upon renewal a landlord has a right to reenter the property, has control of the property, and must inspect the premises to make the premises reasonably safe from dangerous conditions. Even if the commercial landlord executes a contract which requires the tenant to maintain the property in a certain condition, the landlord is obligated at the time the lease is executed to take reasonable precautions to avoid unnecessary danger.” (Mora v. Baker Commodities, Inc. (1989) 210 Cal.App.3d 771, 781, internal citations omitted.)

Examine whether defendant has burden to disprove notice

A property owner can be liable for failing to inspect for hazards, if a reasonably prudent owner would have done so under the circumstances. (See, e.g., Ortega v. Kmart Corp. (2001) 26 Cal.4th 1200, 1205.) In Ortega, the plaintiff slipped on spilled milk but was unable to establish how long the milk had been on the floor. K-mart had not taken reasonable steps to inspect the premises and could produce no sweep reports to show when the milk fell. The Supreme Court held there was a presumption of constructive knowledge by K-mart relating to the dangerous condition of its property. (Id. at 1210.) It was K-mart’s burden to disprove notice in view of the fact that K-mart failed to do what a reasonable premises owner would do under similar circumstances. Thus, if a property owner or one in control fails to reasonably inspect the premises, the burden of proving notice of a dangerous condition may shift to the defendant.

Examine whether defendant bears the burden to disprove causation

In a negligence case, the burden of proof on causation can shift to the defendant where public-policy considerations so demand. (See Galanek v. Wismar (1999) 68 Cal.App.4th 1417, 1426.) A seminal case on the subject of burden shifting is Haft v. Lone Palm Hotel. (Haft v. Lone Palm Hotel (1970) 3 Cal.3d 756.) The Haft family spent a weekend at the Lone Palm Hotel, when mysteriously Mr. Haft and his son drowned in the swimming pool. In a subsequent wrongful death claim by Mrs. Haft, the defendants moved for a directed verdict on the ground that plaintiffs could not prove actual causation of the drowning. But it was established that the defendants had breached a significant safety regulation: the statutory life-guard requirement. The court concluded that the reason the plaintiffs lacked causation evidence was because defendants had failed in their legal obligation. The Supreme Court noted:

To require plaintiffs to establish “proximate causation” to a greater certainty than they have in the instant case, would permit defendants to gain the advantage of the lack of proof inherent in the lifeguard less situation which they have created. (Citations omitted.) Under these circumstances, the burden of proof on the issue of causation should be shifted to defendants to absolve themselves if they can.

(Id. at 772.)

Stairway falls account for millions of traumatic brain injuries each year. Often, your client will have no recollection of the fall itself. Defendants may argue that the plaintiff cannot establish causation because she cannot remember why she fell and no one witnessed the fall. But this argument fails if it can be established that the reason the plaintiff lacks causation evidence is because the defendant violated safety laws, such as building codes or ADA laws, and the violation of the law contributed to the evidentiary gap.

Visually communicate dangerous conditions on stairs

Stairway building codes are often highly technical and cumbersome to explain verbally. Using pictures and graphics to explain the principles is essential. We have found that among the most effective ways to communicate dangerous stairway conditions and safety measures that would have prevented the stairway fall is through a visual depiction of the actual stairway itself. Using an as-built company to take precise laser measurements of a stairway is a less expensive way to get precise, to-the-millimeter measurements of the stair geometry. A more expensive, but more useful way of documenting a stairway is through the use of 3D laser scanning. With laser scanning, an entire room inside a building can be scanned and rendered into a 3D model of the premises. This allows one to “fly” in and around the room to view the stairway at different angles, to “cut in” to the side of a stairway and demonstrate stair height and length (rise and run) measurements, as well as the width of a stairway, and most effectively, to “rebuild” the stairway to show how safe it would have been had the defendants complied with building codes or the basic duty of care.

Because we cannot yet insert a video clip into paper magazines like the one you’re holding, we have provided a video clip of a recent case where the interior of a nightclub was scanned and rendered into a 3D model, where we “flew” around the stairs to demonstrate the myriad safety hazards, and showed how defendant could have cheaply fixed the stairs to prevent the serious traumatic brain injury sustained by our client. Please visit (http://www.veenfirm.com/blog/using-laser-scanning-create-3d-model-demonstrate-unsafe-stairway-conditions-safety-fixes/) to view how effective this was in a recent case, resulting in a substantial settlement.

Examples of building code violations and visual depictions using photographs with graphic

The following is a list of examples of common building code violations and ways to depict them using photographs after a site inspection with an as-built company taking point-to-point laser measurements, and a graphic vendor demonstrating the violations.

The stairway

The stairway in this case was located at a Tahoe compound outside the “Guest Wing/Dormitory” building. The stairway was located under a rough-hewn stone covered bridge that leads from the main house to a round turret structure that houses an internal circular stairway up to the guest dormitory. All in all a rather innocuous-looking, Hansel and Gretel fairy tale feel. But the beauty of the construction masked a myriad of safety issues that resulted in a disabling traumatic brain injury to our 80-year-old client.

The stairway consists of three steps total, none of which is uniform with any other. The first step is rectangular in shape, with boulders encroaching the tread for several inches on either side; the second step is unusual in that it meets neither the CBC requirements for a landing nor for a step, and its shape is best described as an irregular rectangle with a concave curve at the far side; and the third step is a curved step to the threshold of a round top door. Neither the door nor the third step are parallel to the nosing of the first two steps (or step/landing) but rather are canted at a 22.5 degree angle away from the plane of the steps.

Here is how we depicted the half-dozen code violations.

Building Code violations

At the time of the accident, the stairway violated the building code in at least six respects, as follows:

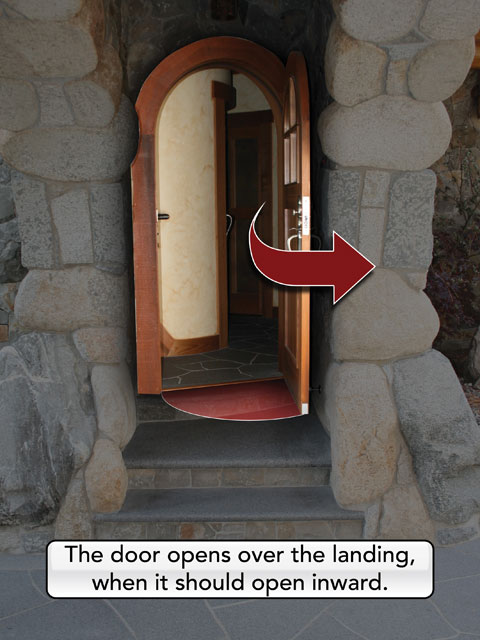

•Violation #1: door swings out over landing

The 2001 California Building Code, section 1003.3.1.6 provides: “Floor level at doors. Regardless of the occupant load served, there shall be a floor or landing on each side of a door.” Under Exception 1.2, the section provides: “A door may open at a landing that is not more than 8 inches lower than the floor level, provided the door does not swing over the landing.” (2001 CBC Section 1003.3.1.6.) The purpose of this code section is to avoid any surprises to a person passing through the door opening. Therefore, it is necessary that there be a floor or landing on each side of doorway. It is permissible to have a step at the doorway, but for safety purposes the door must not swing out over the landing. Here, the door swing forces a user outside the door backwards onto a landing that is not dimensionally safe.

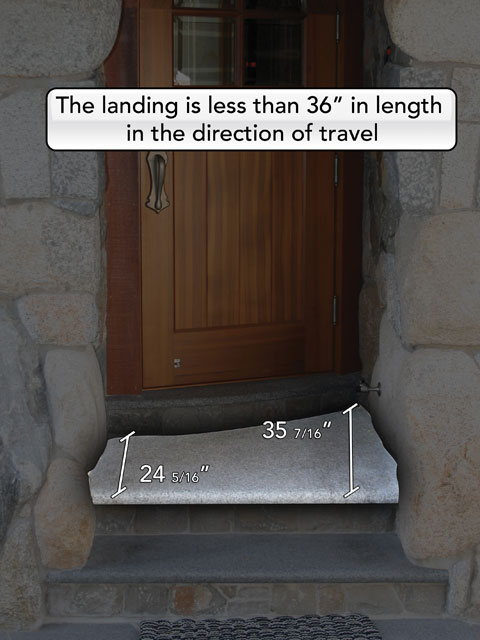

•Violation #2: landing dimension

Section 1003.3.1.7 provides: “Landings at doors. Regardless of the occupant load served, landings shall have a width not less than the width of the door or the width of the stairway served, whichever is greater. . . . Landings shall have a length measured in the direction of travel of not less than 44 inches (1118 mm). EXCEPTION: In [properties zoned as single-family residences], such length need not exceed 36 inches.” (2001 CBC Section 1003.3.1.7.)

Here, the irregularly-shaped landing does not comport with the dimensional length requirements of the Code. The Code requires a consistent and uniform minimum 36 inches in length in the direction of travel for the entire landing space in front of the door. This landing varies in a concave arc from roughly 24” on the left side to 35” on the right. (See detail 5 on CAD drawings, attached hereto as Exhibit 1.) This dimensional irregularity is not what a user of the stairs would expect, thereby creating potential confusion and disrupting one’s gait. Therefore, the landing is not code-compliant and further contributes to the unsafe condition of the stairs.

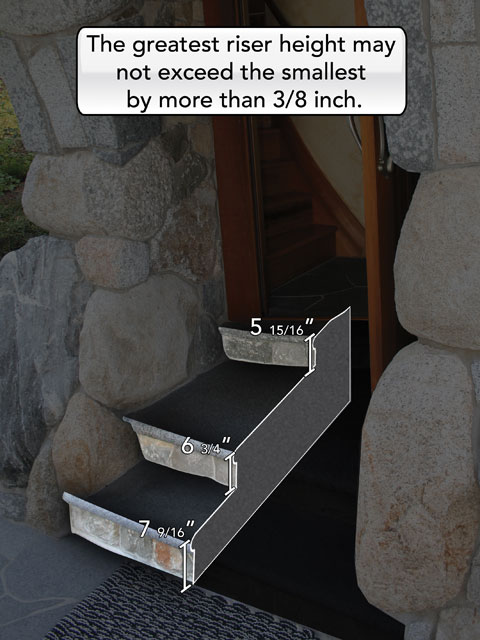

•Violation #3: riser heights are not uniform

Section 1003.3.3 provides: “Rise and run. The rise of steps and stairs shall not be less than 4 inches nor more than 7 inches. The greatest riser height within any flight of stairs shall not exceed the smallest by more than 3/8 inch.” (2001 CBC Section 1003.3.3.) Thus, the greatest variance in height between any two risers may not exceed 3/8 inch. Here, the risers all vary from each other by amounts well beyond what the Code allows:

1st step, 7 and 9/16” at center

The rise of the first step measures 7 and 9/16 inches at center, and ranges from 7 & 13/16 inches at the left to 7 and 5/16 inches at the right. (See Exhibit 1; CAD drawings, details 2, 3, 5 and 6).

2nd step, 6 and 3/4”

The rise of the second step is 6 ¾ inches.

3rd step, 5 and 15/16”

The rise of the third step to the threshold measures 5 and 15/16”.

Thus, the stairway violates the Code because the comparative riser height of all of the steps varies far beyond the 3/8” maximum allowed: (1) the first step is nearly 1 inch higher than the second step, which is 2.5 times greater than the maximum allowed; (2) the first step is 2.5 inches greater than the third step, which is nearly 7 times greater than the maximum allowed; (3) the height of the second step is 1 and 7/16” higher than the third step, which is approximately four times greater than the maximum amount allowed by the code.

These variances in riser heights – not by fractions of inches but rather by a factor of multiples of the Code maximum allowance, cause a user to encounter an unexpectedly asymmetrical stairway which throws off the user’s gait. This code violation further contributes to the unsafe condition of the stairs.

•Violation #4: tread depth

Section 1003.3.3.3 provides: “Rise and run. . . . . “Stair treads shall be of uniform size and shape, except the largest tread run within any flight of stairs shall not exceed the smallest by more than 3/8 inch.”

Here, defendants may take the position that the second step is not a landing because it fails to meet the Code requirements for a landing. If defendants take such a position, the second step still violates this section because it is not uniform dimensionally – its concave shape is not uniform and also differs significantly from the other steps. This code violation also creates a condition not expected by users of the stairs, which they are likely to become confused by, and further contributes to the unsafe condition of the stairs.

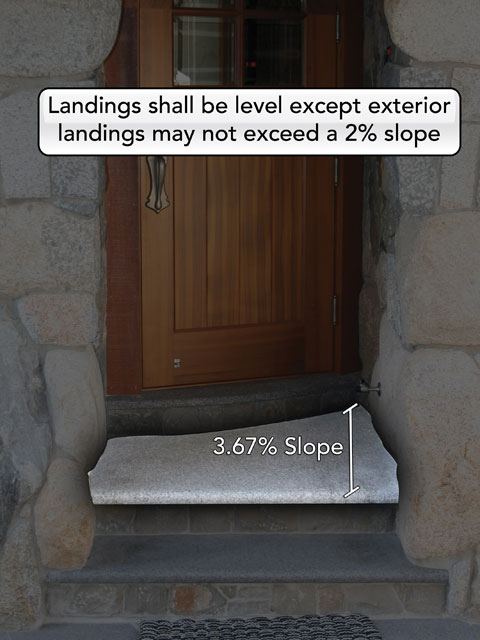

•Violation #5: landing slope

Section 1003.3.1.6 provides: “Floor level at doors. …Landings shall be level except that exterior landings may have a slope not to exceed 1/4 unit vertical in 12 units horizontal (2 percent slope).”

Here, the stairway landing violates the code because the landing’s slope is 3.67 percent, which is 83 percent greater than the code maximum 2 percent. As with the other violations, this code violation also creates a condition that users of the stairs do not expect, are likely to become confused by, and throws off one’s gait.

As a result, this code violation further contributes to the unsafe condition of the stairs.

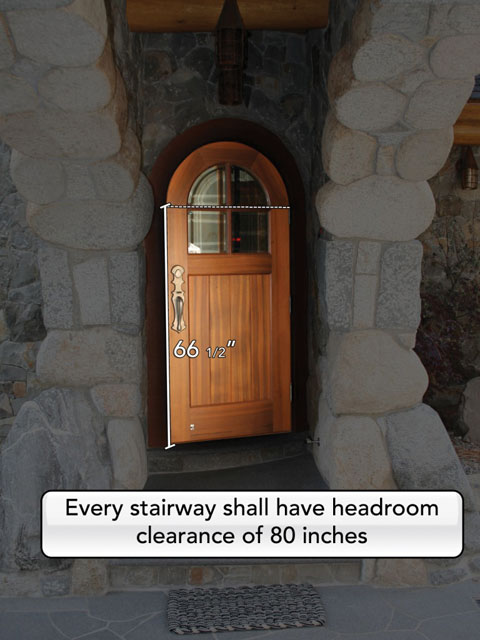

•Violation # 6: headroom clearance

Section 1003.3.3.4 provides: “Headroom. Every stairway shall have a headroom clearance of not less than 6 feet 8 inches. Such clearance shall be measured vertically from a plane parallel and tangent to the stairway tread nosing to the soffit or other construction above at all points.”

Because a step runs continuously along the stairway door, the 6-foot-8-inch headroom requirement applies at all points along the tread nosing at the threshold. The stairway does not meet the headroom requirement, because clearance at points where the rounded door begins its tangent (i.e. from an upward plane beginning at the right and leftmost points on the tread nosing) is only 66 and ½”, more than 14” lower than the Code minimum.

This violation further demonstrates a lack of attention to the building codes then in effect, and provides further evidence that defendants were negligent in their use and maintenance of the property.

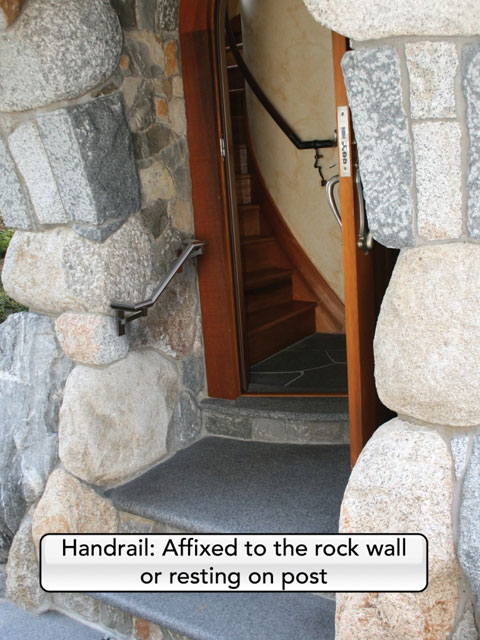

So you’ve got code violations, show me the causation!

A primary attack by defendants in stairway cases is causation. “Who cares if you’ve got building code violations, but how would compliance have prevented the accident?” A handrail violation is the most common building code violation that is intuitively linked to causation. But what of the violations above? Notably, there was no strict code requirement at that stairway, because it only had three risers. This is where it is important to consult with a safety expert or architect. The stairway is a system, and once safety of the system is compromised by the multiple building code violations at the stairs, defendants may not rely on the absence of a strict code requirement for a handrail to avoid liability. Here, given the stairway’s condition – with its uneven and asymmetrical steps – and the many safety laws it violated, numerous safety experts agreed that the “de minimus” cost of a handrail was minimally necessary to protect guests to the property. We used the trial graphic vendor to superimpose a handrail at the property here, to demonstrate that the cheap fix would have also fit in with the overall aesthetic of the property.

Conclusion

Stairway-fall lawsuits present unique challenges in explaining to the jury the technical building code violations and safety measures that would have prevented a fall. Make use of photographs and 3D video modeling where appropriate to effectively communicate these principals to your jury.

Anthony Label

Anthony Label is the team leader of the Label Trial Team at The Veen Firm, P.C. in San Francisco. Anthony’s practice emphasizes aggressive and compassionate advocacy for catastrophically injured plaintiffs. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and children. For more information, see the Website at www.veenfirm.com.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine