Framing the auto case for jury selection and opening statement

Candor, honesty, and listening well will help keep you on track

When the prospective jurors walk into the courtroom, take their seats, roll call is done and they are all sworn in, the judge introduces the lawyers and the parties. The focus is on you at that point. After jurors are seated in the jury box and the judge screens the jurors for hardships and asks preliminary questions, it is time for you, as the trial lawyer, to begin framing the case itself for the jury. Through your words and the questions of counsel, and through their responses, the selection/deselection of juror process begins.

After inquiry and exchanges of thoughts between the lawyers and prospective jurors, peremptory challenges of the potential jurors begins. After this process is exhausted and both sides have agreed upon twelve jurors and the number of alternate jurors, a panel is born and the trial begins.

Each side then has an opportunity to present opening statements. After that, the plaintiff puts on witnesses, establishes what will be the evidence, and it is “game on.” Trial is war. This article suggests methods for framing your trial effectively through the voir dire and opening statement so that as the evidence comes in, the jury understands your case, what the issues are that they need to resolve, and has an effective call to action to find justice.

They are sizing you up

Before you even open your mouth, the jury has been sizing you and the plaintiff team up, along with your opponents. They are noting your body language. How you interact with others. How organized you appear to be. How you behave and interact with the plaintiff. Judging by them is already beginning. Take advantage of this non-verbal communication from the inception. Be polite. Be professional in tone. Never condescending. Care – not just act like you care: Care about those you are fighting for, and those helping you. Remember, how you speak to the court personnel and how you address the Court is noted by them too. Be organized. Do not waste people’s time. Have a plan and a purpose for everything you do.

My friend Dan Ambrose teaches trial lawyering skills and voir dire is a specific area he focuses on with his “Trojan Horse” method (www.trojanhorsemethod.com). I was discussing this article with him and he wanted to offer his own insights with regard to effectively framing through voir dire. Here are some thoughts from Dan, and I’ll respond to his suggestions afterwards.

Purpose of voir dire

To establish the lawyer as the leader, reframe imperfections of our case. Allows the lawyer to show the jury who he is through the topics that he speaks about and the manner in which he communicates. Nobody can do a good voir dire unless he has the ability to stand up in front of the jury and have a calm mind, and have a conversation in the same manner that they would with a friend or a person they just met on an airplane. Ninety-nine percent of lawyers stop listening as soon as they stand up. To truly be effective you must not only listen but reflectively listen. I don’t mean to parrot back what a juror says, but to actually imagine what the juror is talking about, for example;

Atty: Juror #3, have you ever had to take care of a sick or injured loved one?

Juror #3: Yes, in fact my mother recently died from cancer, and I took care of her in her last year. (Juror’s face is visibly “distraught and pained”.)

•Bad follow up:

Atty: I’m sorry to hear that (no change in demeanor of lawyer, no real empathy) −lawyer moves on to next juror, juror feels upset and used.

•Good follow up:

Atty: I’m sorry that you went through this (attorney is imagining juror by his mother’s bed as she is dying, so attorney’s demeanor matches or is in rapport with juror.)

Atty: Juror#3, are you going to be OK sitting here for a week during this trial?

Juror #3: Yes, I will be fine.

Atty: Okay, because a lot of what we talk about during this trial may trigger those memories of what your mom went through.

Juror #3: I will be fine, it was a while ago.

Atty: Okay, well if during the trial you find that it becomes too difficult to sit and listen to the evidence, just let us know, and we will do something about it, ok?

Juror #3: Yes, thank you.

Now the juror feels like you actually care, and the rest of the jury will know you’re actually listening to them, communicating with them, sharing with them.

Beginning voir dire

This is often the most difficult aspect of voir dire. Immediately, you need to establish rapport with the potential jurors. Don’t talk about the law or the facts, start out in general terms. For example:

Atty: As we look around the courtroom, most of us are strangers. As you have experienced, we have to talk to each other. Some of us might be a little self-conscious about how their voice sounds; I know I am. Anyone else ever hear a recording of their own voice and think, “Wow, I sound much different than I thought.” (Raise your hand.)

Juror: Yeah, I was a little surprised.

Atty: It is a little surprising, isn’t it?

Atty: One of the things that we have to do here today is to judge; we constantly make judgments and evaluations of each other. Do we all do this, to one extent or another? (Please raise your hand.)

Atty: In a courtroom we have to judge the facts of the case, and for more than the last 230 years, people just like us have been gathering in courtrooms just like this and passing judgment.

Atty: Here’s my question: Who here is going to have any difficulties, even small ones, if they sit on our jury and are asked to pass judgments here today?

Effectively framing low-impact auto trial

Most people think that a person can’t be hurt unless there is massive damage to the car. This is a major hurdle in most minor damage cases. Here is a frame that helps start to solve this problem:

Atty: Some people think that if there is no damage in a crash, then the occupants can’t be hurt; who here would tend to agree with this?

Juror #3: I do.

Atty: Why?

Juror #3: Well, I have been in a few fender benders, and my car was even totaled, and I wasn’t hurt.

Atty: Totaled? And you weren’t hurt at all? (Total affirmation, with nodding of head.)

Juror #3: I mean my arm was a little sore, but that’s about it.

Atty: Right, cars are built safer than ever. Who agrees with Juror #3?

(You want to find all the folks who tend to agree with this person and discuss with positive affirmation.)

•Now, reframe the dialogue to support your case:

Atty: Who tends to feel differently? That a person can be hurt, even seriously, even if there is only minor damage to a vehicle?

Juror: I do.

Atty: Why? (It is very important to allow the juror to answer the “why” because now they are creating the argument for you.)

Juror#4: Because people are made of flesh, and cars are made of steel, or, if a person is old, they may be more vulnerable, or, if a person already has a bad back, they may be more susceptible, etc.

Atty: Who else feels similar to Juror #4?

Lead this discussion from there. Go back to Juror #3 and those jurors who feel like him.

Atty: And we were discussing how the judge has the right, I have the right, and you have the right not to sit on a case where we may not be able to be fair and objective.

Juror: Yes.

Atty: If this was a divorce case, I would have to tell the judge, “I could be fair, because I’m a fair person, but not objective because of my life experiences, and my beliefs. And I belong on a different case in another courtroom on a case that doesn’t involve divorce, so I can be a fair and impartial juror.” And in this case, if I asked you if you could be fair, I assume you would tell us that you could be fair, because you’re a fair person, but you would have difficulties in being objective?

Juror: Maybe.

At this point you can either choose to explore further the bias of the juror or let it go.

Framing the reason we are here

We need to set the frame as “we are here because the insurance company forced this to trial by being cheap.”

Atty: Which ones of us have been in an accident, or know someone who has?

Juror: I have.

Atty: Did you file a lawsuit?

Juror: No.

Atty: Were you hurt?

Juror: Yes, but I settled with the insurance company.

Discussion: This story line happens over and over, because most cases settle. The jury starts to believe that this case didn’t settle because either the lawyer or client is greedy.

Atty: Let me ask you this question: What would you have done had the insurance company refused to pay your medical bills and offered you hardly anything for your pain and suffering?

Juror: Well, then I guess I would have had to sue them.

(Now they know why we are here.)

The goals of voir dire

The advice and suggestions of Dan echo successful approaches I have used, and seen so many others effectively use in winning the auto case. The idea is to get out of the way right off the bat any idea that your client’s injuries have to have some relationship to the visible property damage.

CAALA’s Trial Lawyer of the Year, Gary Dordick, emphasized this concept to me 20 years ago, and I have asked the same question to jurors through the years: “Any of you ever known someone who was hurt in a car crash but there was either very little or no visible property damage, but they really got hurt?”

This question always gets positive dialogue going. Because you don’t represent the car, you represent the person. Similarly, get the jury to agree that even if you had a weaker spine because of age or prior injury, that any new pain or injury resulting from a case should be compensable if it is the other person’s fault, whether or not others would have been hurt in the same crash.

Rapport, as Dan points out, and honesty are key. Former CAALA president Mike Alder does fantastic voir dire, and he tells the jury to let him have it, all the negatives. Be honest. He does not fight it, he embraces it. “Tell me more about that. Who here feels the same?”

By creating an honest dialogue, jurors don’t feel threatened to be honest, and will expose their true biases, making use of peremptories more precise.

Another great trial lawyer, Nick Rowley, talks about asking the jury to be brutally honest with him. And he supports the approach of being very candid with them, telling them you’re nervous if you are, telling them your fears and concerns in getting a fair verdict with the facts and witnesses you have.

The thread through all these approaches is candor, honesty, and listening well.

Framing an effective opening statement

To me, the best opening is concise, and tells a story that you will back up with witnesses and evidence. Eye contact and a good conversational tone of voice is smart. Use demonstrative evidence if the opposing side and the Court allow.

With a brain-injury case, for example, I’ll use a brain model if allowed, or with a spine case, a skeleton is allowed, because jurors are visual, and what you say early on is key. I hate lecterns and don’t read too many notes if possible. You should be a storyteller and a truthful one, too. And embrace the defense you anticipate, respectfully letting the jury know, if true, it is bought and paid for junk science and garbage, or people with a bias to shirk responsibility (again, if true!).

Make your words count. Use action words to describe the impact. Most car crashes have an energy pulse that lasts one-tenth of a second, but the impact lasts years, and here’s how we’ll prove it. Explain why the injuries hurt. Why they are chronic. Don’t be afraid to ask for money and be clear about why you’re there.

Trial lawyer and author David Ball says, “If you’re afraid to ask for it, they’ll never give it.” Don’t wait until the end of trial to get to the point – and be embarrassed by it – that this is all about money.

The following checklist is useful to remember: Have a plan for the order of your presentation and map out the trial, from opening statement to witness order, to evidence received.

Good generals have good plans before engaging in battle. Be yourself. You need to not try to be Genie Harrison or Chris Spagnoli or Arash Homampour or Robert Simon or….be you!

Wear what you feel comfortable wearing. Let your personality shine through. Be interesting with your tone of voice. Modulate and pace yourself and your tone. Are you going too fast? Nervous? Droning on? Then Practice.

It’s not just what you say

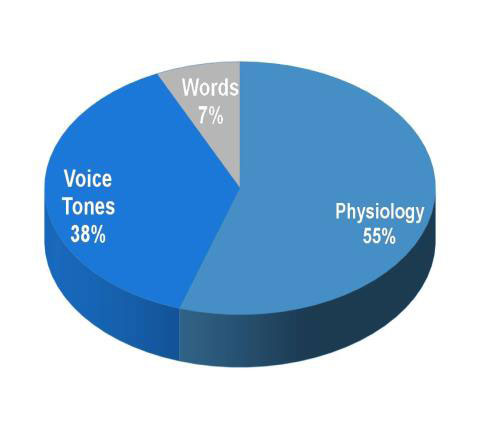

Tape yourself. Slow down. Keep your voice at a pleasant volume. Some studies conclude that almost all aspects of how people receive you as a communicator are attributable to things aside from your actual message! UCLA Professor Albert Mehrabian’s famous 1967 study concluded that 55 percent of the impact was based upon how you looked, 38 percent on how you sounded, and only 7 percent on what you said!

The point is pretty clear: people care, and care a lot, about how you talk to them, how you move, how you modulate your voice, and so visual and vocal communication skills should not be underestimated. It matters who is the messenger and how they deliver. Don’t get emotional and find yourself yelling or being an angry spectacle. As the great Charlie O’Reilly used to teach me and others, don’t steal the jury’s emotion. Let them get angry about the injustice of the defense approach, not you.

Tell a good story

A good story has a memorable theme. Here are some examples.

“This trial is about personal responsibility. The consequences of one’s behavior.”

“They ran from the scene but they can’t run from this courthouse.”

“They chose profits over people.”

“They broke their own rules. If you break it, you gotta fix it.”

Themes that are simple and conjure up a visual can be stated during trial and tied back together with the closing argument. They provide a sound basis to understand a case.

Chris Dolan, an outstanding trial lawyer and former president of CAOC, uses as an example about the orange and the egg. “Most people are like the orange, which you can drop on the table, and it bounces. But the plaintiff here was like this egg,” he’ll say, “which shatters with the same impact.” Then people get it, why they are there. They learn your trial’s story, and hopefully embrace you as the storyteller and a credible lawyer. Both are key.

Concluding thoughts

You don’t need to be a big personality. You do not need to be the focus too often. But you need to establish rapport early. You want to have the jury understand the crash and why it is the defendant’s fault, and how it changed the plaintiff’s life. You want to very directly, brick by brick, make the case you told the jury you’d deliver in opening.

You do not want to be embarrassed to ask for a full measure of justice in terms of money. How to effectively ask for money is a whole separate article, but suffice it to say your money arguments must be logical and backed up by the evidence. Some I’ve used successfully include:

• In a weight-bearing, articulating joint injury (knee, hip, ankles) trial:

“The average person takes 5,000 steps a day. We spend maybe 16 hours a day thinking, feeling, dreaming, and doing. She now does that with pain, depression, limitation — and the fun stuff, much of it is gone. And now, even worse, she’s not safe, she can’t move well, she can’t…..”

“If there was a newspaper ad that read, “Hey, we’ll pay you $20,000 a year but first, we’ll have to break your leg, have it not heal right, cause some nerve damage, put you through a couple life-threatening surgeries. Who in their right mind would sign up for such a job? No one.”

•In a brain-injury trial

“The brain is the most intricate, delicate organ, the window to our souls, the center of what makes us feel, think, move, do…. There’s no pill or surgery to fix it once it’s broken…”

These are the kinds of approaches to damages you should think about. Talk with fellow trial lawyers. Focus group your case, even informally. Hone your message. Change the order of a key witness or two and see how that works. And prepare your witnesses and yourself so the trial moves in a logical way, with a good pace.

Remember to spend a fair amount of time emphasizing the choices the defendant made. In a left-turn case I had recently, it was critical for me to emphasize the whole sequence of events to demonstrate that the defendant was rushed, thoughtless, and by not paying enough attention and thinking only of himself, he became almost blind to our vehicle directly in front of him, and then two 3,000 lb. vehicles crashed into each other violently. The plaintiff was thrown into the seatbelt, which cinched up at the same time. He whacked himself on the steering wheel, sprained his wrist, cracked his ribs, and suffered nerve and disc injuries in the low back, all because of that violence. All due to negligence. All the while, the plaintiff never anticipated the defendant acting so dangerously. He was just on his way home to make dinner

In summary, Dan’s tips are good reminders to me that the voir dire requires you framing the issues, while also not being confrontational. Learning, listening, you can find a fair jury, and with the right framing of the opening and the right witnesses order and evidence, you’re on track to obtain justice.

Joseph M. Barrett

Joseph M. Barrett served as 2015 President of the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles. He is a partner at Layfield & Barrett specializing in major, complex cases concerning catastrophic injury or death and impact litigation across the diverse fields of tort law including civil rights, insurance bad faith, product liability, professional negligence, vehicle and premises liability and road design. Mr. Barrett served the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles (CAALA) as the President in 2015 and is a member and supporter of the American Association for Justice.

Daniel Ambrose

Daniel Ambrose has tried over 150 jury trials and spent the last decade working on advancing and teaching advanced trial skills. Through 20 years of practice, he has found a unique method to help trial lawyers efficiently master their skills, The Trojan Horse Method. The Trojan Horse Method is considered a “complete system,” from voir dire to rebuttal. Dan currently lives in Manhattan Beach, California and now focuses on civil and criminal trial work, consulting, trial coaching and teaching. He is a frequent speaker on witness preparation, direct examination, and voir dire.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine