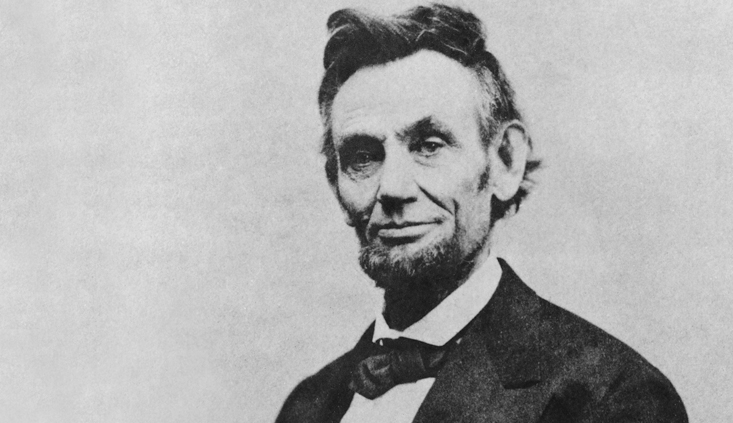

What if Abraham Lincoln had lived to practice law again?

A look at what history suggests Lincoln’s life might have been like had he survived the presidency

History is full of speculative “what- ifs” that send our imaginations wondering: “What if” Abraham Lincoln had not been assassinated by John Wilkes Booth? “What if” Lincoln had finished his second presidential term and honored his pledge to return to practice law with his partner in Springfield, Illinois? Let us suspend the reality of history and explore these questions.

Abraham Lincoln makes a promise

In February 1861, the town of Springfield turned out in jubilation to honor President-elect Abraham Lincoln and wish him well as he began his journey to the nation’s capital to take the oath of office as the 16th President of the United States. Lincoln had weathered a divisive election centered on the issue of slavery and the country was on the brink of fracturing. In addressing the assembled well-wishers, Lincoln must have felt some melancholy knowing that he was closing the chapter of his life as a lawyer that had encompassed nearly a quarter century at the bar.

As Lincoln said his farewells and readied to board a train to Washington to lead the country, his law partner William Herndon turned to him and inquired about the future of the law practice that the two had maintained in a cramped office on the courthouse square in Springfield. Lincoln requested that Herndon allow the practice’s signboard to continue during his presidency: “Let it stand there undisturbed. Give our clients to understand that the election of a president does not change the firm of Lincoln and Herndon. If I live, I’m coming back sometime, and we’ll go right on practicing as if nothing ever happened.”1

A war-weary nation prepares to recover

The Civil War that followed after Lincoln assumed the presidency took a heavy toll on both the nation and its leader. As the horrific struggle between the North and South raged for four long years, Lincoln’s cares for the country’s future and the lines on his face deepened. Even while Lincoln directed the war effort, personal tragedy struck home with the passing of his son Willie in the White House in 1862.2 During the following year Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation as the tide of battle began to turn in the Union’s favor.3 With his re-election to another four-year term in November 1864, Lincoln began to envision a united country with the rebellious states reintegrated into the republic.4

In his second presidential inaugural address on March 4, 1865, a fatigued Lincoln delivered a hopeful message about mending the divided nation and moving it toward reconciliation: “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to all do which may achieve and cherish a just and last peace among ourselves and with all nations.”5

Some say that assassin John Wilkes Booth was in the crowd on the Capitol steps to hear Lincoln’s sanguine words. Hardly more than a month later, on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Booth fired the bullet that ended Lincoln’s life and changed the course of American history.6

We are left to speculate

One can only speculate how different the post-Civil War reconstruction of the country might have been under a president who was determined to use the weight of his office to ensure that the “house divided” was restored fairly and equitably. Lincoln’s belief that the breakaway states and their citizens should be treated with civility surely would have been tested by those salivating with victory and vengeance against the former Confederacy.7 But Lincoln’s conception how to bring the former warring sides together harmoniously was not to be.

Even if Booth’s cowardly plot had been thwarted and President Lincoln had lived out the four years of a second term to try to heal the nation’s wounds, a new president would have been inaugurated on March 4, 1869. An exhausted Abraham Lincoln then would be deciding how to spend the next chapter in his life beyond his two difficult terms as president.

A trip to California

Abraham Lincoln had travel on his mind as something he might like to do after finishing his presidency. Just hours before he departed the While House for the evening of entertainment at Ford’s Theater from which he never returned, Lincoln met with Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax and invited him to accompany the Lincolns for a night out. Colfax declined the invitation and told Lincoln that he was about to depart for California. Lincoln reaffirmed something to Colfax that he had said several weeks before regarding his intention to visit California once the transcontinental railroad was completed.8 This was a highly anticipated event in which Lincoln was greatly involved that was expected to occur at about the time he that would have completed a second term in 1869.9

Lincoln’s ambition of travel to California was never fulfilled. But even if he had had the opportunity to enjoy himself with some travel after leaving the White House, Lincoln still would have been confronted with the necessity of earning a living. A return to the practice of law was an obvious means for Lincoln to sustain himself financially.

Lincoln would have had good reasons to want to regain financial stability after living in the White House. He was not a wealthy man when he entered his first term of office in 1861. Although his law practice had been good to Lincoln and allowed him to gain middle-class respectability, his worth was not more than about $15,000 when he became president.10 Despite Lincoln’s simple wants, maintaining the White House had been expensive. Nearly everyone knew the reputation of his wife Mary Lincoln as a compulsive buyer and hoarder with extravagant and expensive tastes.11 It would have been natural for Lincoln to follow a path back to the practice of law to keep her satisfied.

You can’t go home again

Although the signboard for the Lincoln & Herndon law firm may have remained hanging for the duration of Lincoln’s term of presidential office, it seems unlikely that the old partnership would have resumed as it had been.

The Lincoln & Herndon partnership had endured successfully since 1844. Lincoln had been the driving force of the relationship during those practice years. His respected legal skills brought in much of the business, and he handled the main litigation and trial work. While the two partners always evenly split the attorneys’ fees that were earned, the younger Herndon often labored as the drudge who handled the day-to-day details and was less than a true equal.12

The two probably had less in common than some law partners. Lincoln had a quick wit, endearing social skills, and a razor-like analytical and practical mind that made him a first-rate trial lawyer, especially in front of a jury. The sixteen-year relationship between the partners was defined by mutual respect, but Herndon was more of a backroom lawyer who possessed ordinary legal talent. He tolerated some of Lincoln’s peculiar habits, such as sometimes dressing less than fastidiously.13 But the more straight-laced Herndon allowed Lincoln’s frequent absences for politicking, particularly during Lincoln’s two-year term in Congress from 1847 to 1849.14

When Lincoln was not out on the horse-and-buggy “mud” circuit traveling from one rural county courthouse to another in central Illinois or litigating in Chicago, he would arrive at the office daily at around nine o’clock and assume his customary place lounging on a comfortable couch reading a newspaper or chatting with virtually any visitor who might wander into the office.15 Total chaos could reign on the occasions when Lincoln brought his young sons into the office for a visit. They would race around playing and getting into all sorts of trouble, which annoyed and tried the patience of the more orderly Herndon.16

While Herndon was tending to the more conventional aspects of a law practice, Lincoln was constantly improving his trial skills and broadening his legal and political contacts.17 By the 1850s, the times were passing when Lincoln and Herndon represented farmers and locals for nominal fees of $5 to $20 out of their Springfield office or on the courthouse circuit.18 Lincoln’s preeminence as an effective trial attorney grew larger and larger in the decade after he returned from Congress in 1849 to pursue the practice of law and his political ambitions in earnest.19 As Lincoln’s reputation developed, so did the magnitude of the cases on which he was retained and amounts of legal fees that followed.20

No matter how sincere Lincoln might have been about resuming the practice of law with his old law partner after his presidency, it is difficult to see him returning to the little office in Springfield and beginning his mornings by leisurely socializing after he had served as president for eight intense years of office. Lincoln’s life had dramatically changed at the White House, where his days were filled with long working hours that offered little respite from the worries of war, decision-making, legislation, politics, social obligations and family matters.21

While the Lincolns retained their Springfield home after taking up residence at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, it is doubtful that they could have lived in peace after Lincoln’s second term of office. The constant flow of opportunists, favor seekers and souvenir hunters who had traipsed through the executive mansion during his presidency would not have given him any rest in his Springfield office even after he had nothing more to offer.22 There is little reason to believe that such interferences, so unconducive to the practice of law, would have ceased if Lincoln had resumed his law practice where he had left off.

It also is questionable whether Mary Lincoln, a high-strung, hugely pretentious and self-preoccupied First Lady, would have tolerated Springfield’s small town society after experiencing the advantages of Washington and New York culture. She had greatly enjoyed her role of entertaining at the executive mansion. The fashions and luxuries to which Mary Lincoln had decided that she was entitled were abundant in the cosmopolitan metropolis of Chicago and scarce in the provincial downstate Illinois capital of Springfield.23

The big shoulders of Chicago

Abraham Lincoln had worked hard as an Illinois legislator in the 1830s to ensure that Springfield would become the state capital and was proud that his law office was located there.24 By the 1850s, however, Chicago had become the commercial center of Illinois and the Midwest. Chicago, the town that Lincoln biographer Carl Sandberg called “the city of the big shoulders,”25 continued to grow by giant leaps and bounds after Lincoln’s election in 1860 and was an industrial powerhouse with a burgeoning economy and dynamic marketplace by the end of the decade that followed Lincoln’s first inauguration in 1861.26

By the mid-19th century, Chicago was where the big stakes and most lucrative legal cases for lawyers were heard and the better known and most capable attorneys were retained. Lincoln’s considerable abilities and reputation had garnered him a share of such representation.27 It was not unusual for him to be found in Chicago for trials and appeals and, on many occasions, for political reasons as he was a large player in the emerging Republican Party.28

For such reasons, Chicago rather than Springfield would have been a more logical place for Lincoln to relocate if he were to resume the practice of law. It would have been a natural fit for him. He had longstanding legal and political friends in the city where his most ardent supporters had secured him the Republican nomination for president in 1860.29 There would have been a variety of interesting and rewarding opportunities for a former president who had just left office after saving the country from disunion and leading it forward in reconstruction.

Practicing law in the Gilded Age

Trial work is hard work and requires considerable stamina. After taking charge of the country and guiding it through its most troubled times, one wonders if Abraham Lincoln would have had the physical strength and mental drive to pick up where he had left off as an energetic trial attorney. Indeed, many had commented how tired and haggard Lincoln looked after piloting the ship of state through its roughest storm.30 Moreover, much had changed in America in the Gilded Age that followed the Civil War.31

Nonetheless, aside from the rough and tumble of politics, the law was Lincoln’s stock-in-trade and financial circumstances might have caused him to again hang out a shingle. In a time before Congress legislated presidential pensions,32 he would have had to find a means of support. It is problematic to guess whether Lincoln might have had the assistance of a benefactor, such as author Mark Twain who provided support to the cancer-stricken and destitute Ulysses S. Grant while that former president was writing an autobiography to sustain his family.33

A paradigm for such a law practice might have been the law career forged by Robert Lincoln, the only of four sons of Abraham and Mary Lincoln who survived into adulthood.

Although he was a distinguished lawyer, Secretary of War, Ambassador to Great Britain and a captain of industry, Robert Lincoln has been largely forgotten in the haze of history.34 Few today realize that a son of Abraham and Mary Lincoln lived into the twentieth century to sit with President Warren Harding and Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial when it was dedicated on May 30, 1922, nearly sixty years after his father’s death.35

Robert Lincoln was a student at Harvard during the first several years of the Civil War. As much as he wanted to patriotically enlist for the war, he was forbidden from volunteering by his fearful mother who had already lost two sons to early deaths.36 Robert had had an ironic brush with near death while an undergraduate. In 1863, while coming home to visit at the White House, he tumbled from a railroad station platform towards the track of an oncoming train. He was caught and rescued just in time from a sure death by Edwin Booth, the brother of Abraham Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth.37

In 1864, Robert graduated and briefly attended the Harvard Law School. His parents finally relented to his urge to join the military and secured him a position as an officer aide to General Grant.38 He was with Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865, when Lee surrendered and at the White House less than a week later when his father took his ominous last carriage ride to Ford’s Theater.39

Following the completing of arrangements for laying the assassinated president to rest in Springfield, Robert was admitted to the Illinois Bar and established his law practice in Chicago in 1867.40 His innate talent, diligence and name recognition enabled him to easily lure business. A founding member of the Chicago’s first organized bar association in 1874,41 his clients included some of the most powerful corporations and titans of industry of the day.42

Robert Lincoln’s successful business law practice representing the movers and shakers of industry and commerce was a far cry from that of his father, whose legal career for many years largely consisted of rendering advice and trying cases for clients of modest means for small amounts while riding the judicial.43 But the nature of America’s economy and the practice of law had drastically shifted to an era of domination of business by large corporations and greater legal specialization after the Civil War.44

The Law Offices of Lincoln & Lincoln

What law firm would not have relished as a senior partner a former president of the United States whom a colleague at the bar called “a real lawyer’s lawyer”?45

With his name on the front door of a law partnership with his son Robert, Abraham Lincoln would have been an instant draw to bring in clients of the thriving commercial world of the time. For that matter, Lincoln was known to have represented most any client who sought to retain him so long as the nature of the representation did not offend his moral sensibilities.46 For him, business was business so long as it ethically earned attorneys’ fees and he could do the work with a clear conscience.47 Lincoln’s versatile repertoire of practice experience had included a broad range of property disputes, contract interpretation situations, tax matters, personal injury cases, divorces and criminal defense on which he could have capitalized.48

While he had represented many small folks in his legal career, Lincoln was not a stranger to representing companies, large and small. He had gained a reputation as a “railroad attorney” based on serving as counsel for a number of railroad companies during the 1850s. However, as he had both defended and sued railroads a number of times, it would be unfair to type-cast him.49 Given his past adaptability, one perhaps could postulate Abraham Lincoln serving as a corporate attorney or board member.

Nonetheless, one must question whether Abraham Lincoln could have reconciled his legal career devoted to servicing ordinary people with representation of the dominant corporations that burgeoned after the Civil War. His son Robert had not come up the hard way like his father. He became wealthy representing corporate interests such as insurance companies on claims after the great Chicago fire of 1873 and the Pullman Palace Car Company, which controlled railroad sleeping cars throughout the country. Robert played a substantial role in advising this client during the infamous Pullman labor strike of 1894 that shut down half of the country’s railroads and was quelled with deadly force when President Cleveland called in federal troops to stop striking workers from interfering with rail traffic.50

The real Abraham Lincoln

Considering his long history representing “little guys” as a circuit riding lawyer in rural Illinois, it is highly debatable that the war-worn former president would have been the right fit for such a corporate practice. Although he had represented large economic interests at different junctures over the span of his career, Lincoln continued to represent the average man in times of legal distress throughout his nearly quarter century at the bar.51 His identification with ordinary people stemmed from his own humble origins, which was reflected in his personal and political philosophies. Indeed, Abraham Lincoln was describing his own deep-felt empathy for ordinary workers when he said that government should be “of the people, by the people and for the people” in concluding his Gettysburg address.52

Lincoln’s story is the American story. He was a self-educated and self-made man who worked diligently to lift himself by his own bootstraps to rise from a life of manual labor and poverty to become a professional with some financial means and, ultimately, presidential power. He had maximized his own possibilities in a free market economy and believed that others should have an equal right to do so.53

Consistent with his own background that had taught him that advancement in life comes with personal effort and hard work, Lincoln did not let even the Civil War stand in the way of legislation that promoted self-improvement, enhanced opportunities and economic development for all. Even while war was waging around him, Lincoln advocated for legislation such as the Morrill Act founding the land-grant college system, the Homestead Act providing free land to farmers and the Transcontinental Railroad spurring commerce and economic development.54 While he never was able to put into practice his evolving views about the possibilities of the former slaves in a post-Civil War society, he viewed government as a beneficial force that could allow them to integrate into the mainstream economy.55

Based on his background and character, Abraham Lincoln earned nicknames like “the Rail Splitter” for his log cabin origins, “Honest Abe” for his genuineness and the “Great Emancipator” for his moral courage against slavery. It is difficult to imagine such a man devoting his remaining years serving as a counsellor representing the rich and powerful of the Gilded Age. As an attorney who was known to represent “all comers,” Lincoln would have been uneasy with clients who espoused the laissez-faire philosophy of the latter 19th century that emphasized amassing capital at the expense of the common person.

In the 1830s, Illinois legislator Lincoln had championed economic development through joint public and private efforts, such as building canals and railroads that promoted economic wellbeing for everyone.56 In the years after the Civil War, economic activity became dominated by trusts that exercised broad control over industries and “robber barons” more interested in concentrating corporate and personal wealth and taking the spoils for their own than the public good.57 As an attorney who had represented many people of limited means, Lincoln would have been uneasy providing his services to the faceless corporations of the latter 19th century.58

Thus, it is difficult to visualize Abraham Lincoln practicing law with his son Robert and representing the giant corporations of the postbellum era. After a heart-to-heart discussion with his son about the factors that had molded Lincoln into what he was, the former president most likely would have declined to join a law firm of Lincoln & Lincoln. Having also ruled out a return to his past partnership, Lincoln might have taken that trip to California or perhaps joined the speaking circuit to talk about the American Dream of economic equal opportunity for all.

“What-ifs” don’t count

It may be speculated about what Abraham Lincoln might have done if he had lived out his second term of office and beyond. But history does not allow itself to be revisited. The sixteenth president of the United States was never able to carry out his own vision of a restored union or make good on his promise to rejoin his law partner after serving as president.

While it is alluring to speculate on “what if” Abraham Lincoln had lived to practice law again and begun a new phase of life at the bar, one is still left with the question that Americans considering important matters of state have asked for a hundred and fifty years: “What would Abraham Lincoln have done?”

Michael L. Stern

Judge Michael L. Stern has presided over civil trial courts since his appointment to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 2001. He is a frequent speaker on trial practice matters. As an attorney, he tried cases throughout the United States. He is a graduate of Stanford University and Harvard Law School.

Endnote

1 WILLIAM H. HERNDON & JESSE W. WIERK, ABRAHAM LINCOLN: THE TRUE STORY OF A GREAT LIFE 193-194 (1885) [HERNDON & WIERK].

2 WILLIAM F. GIENAPP, ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND CIVIL WAR AMERICA: A BIOGRAPHY 47, 104 (2002). The death of Willie Lincoln in the While House in 1862 caused overwhelming anguish to his parents. He was seen as possessing his father’s sense of humor, keen intelligence and kindly

disposition.

3 Lincoln’s initial objective in the Civil War was to save the Union. He personally drafted the Emancipation Proclamation in mid-1862 and discussed extensively with his cabinet members of Congress before he decided to issue it effective January 1, 1863. In order to avoid a perception that the Emancipation freeing the slaves in the Confederate territories was a last-ditch effort to save face for a Union army that had been losing against the enemy, Lincoln held off issuance until after a solid military victory was finally attained at Antietam in September 1862. Emancipation broadened the objectives of the war to abolishing slavery. Through its issuance, Lincoln came to be known at the Great Emancipator. MICHAEL VORENBERG, THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION: A BRIEF HISTORY WITH DOCUMENTS 14-17 (2010); DORIS KEARNS GOODWIN, TEAM OF RIVALS: THE POLITICAL GENIUS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 481-482, 497-501 (2005) [GOODWIN].

4 CHARLES B. STROZIER, LINCOLN’S QUEST FOR UNTION 257-258 (2nd rev. ed. 2001).

5 Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, SPEECHES AND WRITINGS 1859-1865, 685-686 Don E. Fehrenbacher ed. 1980); See also, RONALD C. WHITE, JR., LINCOLN’S GREATEST SPEECH: THE SECOND INAUGURAL (2002).

6 WILLIAM C. HARRIS, LINCOLN’S LAST MONTHS 140 (2004); EDWARD STEERS, JR., BLOOD ON THE MOON: THE ASSASINATION OF ABRHAM LINCOLN 113-118 (2001). Cf., MICHAEL BURLINGAME, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, A LIFE II:558 (inset photo) (2008) [BURLINGAME].

7 BURLINGAME, id. at II:587-588; CARL C. DEGLER, One Among Many: The United States and National Unification, in LINCOLN THE WAR PRESIDENT 248 (Gabor S. Boritt ed., 1992).

8 GOODWIN, supra, note 3, at 734.

9 Lincoln was a strong proponent of railroads throughout his life. He advocated for the 1862 Pacific Railroad Act that enabled the transcontinental railroad to be built, made route suggestions and followed the progress of construction right up to his death. He viewed the railroad as an east-west connector that would secure the western states and territories for the United States. STEPHEN E. AMBROSE, NOTHING LIKE IT IN THE WORLD: THE MEN WHO BUILT THE TRANCONTINNENTAL RAILROAD 1863-1869, 83-84, 128-132 (2000).

10 HARRY E. PRATT, THE PERSONAL FINANCES OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 124 (1943) [PRATT].

11 JEROLD M. PACKARD, THE LINCOLNS IN THE WHITE HOUSE: FOUR YEARS THAT SHATTERED A FAMILY 88-89, 176-178 (2005) [PACKARD].

12 DAVID HERBERT DONALD, LINCOLN’S HERNDON 37 (1948] [DONALD, HERNDON].

13 HERNDON & WIERK, supra, note 1 at 280 (“His habits were very simple. He was not fastidious as to food or dress. His hat was brown, faded, and the nap usually worn or rubbed off. He wore a short cloak and sometimes a shawl. His coast and vest hung loosely on his gaunt frame, and his trousers were invariably too short.”); HENRY CLAY WHITNEY, LIFE ON THE CIRCUIT WITH LINCOLN 55 (1940) [WHITNEY] (“He probably had as little taste about dress and attire as anybody that was ever born; he simply wore clothes because it was needful and customary.”).

14 Lincoln’s life-long interest was politics. Beginning in 1834, he spent most of the next thirty years participating in political campaigning, speaking and running and holding political office for himself and others. He served as an Illinois legislator (1834-1842) and member of the United States House of Representatives (1847-1849) and candidate for the United States Senate (1856 and 1858) and president (1860 and 1864). His frequent public speaking engagements served to enhance his talents as a lawyer and gain recognition to run for public office. DONALD, HERNDON, supra note 12, at 74, 94, 161 (1995); CHRIS DeROSE, CONGRESSMAN LINCOLN: THE MAKING OF AMERICA’S GREATEST PRESIDENT 72 (2013).

15 ALBERT A. WOLDMAN, LAWYER LINCOLN 54 (1936) [WOLDMAN].

16 DONALD, HERNDON, supra note 12, at 159-160.

17 JOHN B. FRANK, LINCOLN AS A LAWYER, 42-43, 88-89 (1961) [FRANK]; WILLIAM LEE MILLER, LINCOLN’S VIRTURES: AN ETHICAL BIOGRAPHY 95-97 (2002).

18 PRATT, supra note 10, at 25-29, 51-52.

19 DON E. FEHRENBACHER, PRELUDE TO GREATNESS: LINCOLN IN THE 1950’S 17-18 (1962).

20 MARK E. STEINER, AN HONEST CALLING: THE LAW PRACTICE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 137, 160-161 (2006) [STEINER].

21 See, WILLIAM O. STODDARD, INSIDE THE WHITE HOUSE IN WAR TIMES: MEMORIS AND REPORTS OF LINCOLN’S SECRETARY 47-53, MICHAEL BURLINGAME (ed. 2000).

22 The line of officer-seekers and other supplicants at the White House was never-ending. At one point, Lincoln’s son Tad cleverly took up a collection of five cents from everyone in line. ELIZABETH SMITH BROWNSTEIN, THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE MAN AND HIS PRESIDENCY: LINCOLN’S OTHER WHITE HOUSE 29-32 (2005).

23 PACKARD, supra note 11, at 172-175.

24 DAVID HERBERT DONALD, LINCOLN 63-64 (1995) [DONALD, LINCOLN].

25 CARL SANDBURG, “Chicago” in CHICAGO POEMS (1916).

26 There was dynamic rapid population growth in mid-19th century Chicago as America transformed from an agrarian to industrial society. Chicago-associated names like Western Union, McCormick, Pullman, Amour and Swift came to symbolize the city’s industrial might. DONALD L. MILLER, CITY OF THE CENTURY: THE EPIC OF CHICAGO AND THE CENTURY OF AMERICA 96-97, 116 (1996).

27 BENJAMIN P.THOMAS, ABRAHAM LINCOLN: A BIOGRAPHY 158 (1952); WOLDMAN, supra note 15, at 171-174.

28 WOLDMAN, supra note 15, at 141-146.

29 DONALD, LINCOLN, supra note 23, at 246-250.

30 STEPHEN B. OAKES, ABRAHAM LINCOLN: WITH MALICE TOWARD NONE – THE LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 409-410, 417 (1977).

31 The term Gilded Age is derived from Mark Twain’s 1873 novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today that satirized the large social problems of the late 19th century caused by the rapid industrialization of the United States that Twain viewed as being covered over by a thin gold gilding. See, CHARLES W. CALHOUN (ed.), THE GILDED AGE: PERSPECTIVES ON THE ORIGINS OF MODERN AMERICA 1 (2nd ed. 2006).

32 Widow Mary Lincoln vigorously lobbied for a pension, which Congress finally legislated and President Grant signed into law in 1870 for $3,000 per year. JEAN H. BAKER, MARY TODD LINCOLN: A BIOGRAPHY 299-303 (1987).

33 CHARLES B. FLOOD, GRANT’S FINAL VICTORY: ULYSSES S. GRANT’S HEROIC LAST YEAR 98-102, 129 (2011).

34 JASON EMERSON, GIANT IN THE SHADOWS: THE LIFE OF ROBERT T. LINCOLN 235, 301-303 (2012) [EMERSON].

35 Id. at insert plate, 291.

36 DONALD, LINCOLN, supra note 24, at 571.

37 EMERSON, supra note 34, at 80.

38 DONALD LINCOLN, supra note 23, at 571.

39 Id. at 592, 598; GOODWIN, supra note 3, at 734.

40 EMERSON, supra note 34, at 37.

41 Id. at 187.

42 Robert Lincoln represented some of Chicago’s largest and most influential corporations of the era, including Chicago Edison Electric Company, Chicago Telephone Company, Pullman Palace Car Company (later Pullman Company) and a subsidiary of John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. EMERSON, id. at 129, 343-344.

43 BENJAMIN P. THOMAS, ABRAHAM LINCOLN, A BIOGRAPHY 92-95 (1932).

44 STEINER, supra note 20, at 160.

45 ALLEN D. SPEIGEL, A. LINCOLN, ESQUIRE: A SHREWD, SOPHISTICATED LAWYER IN HIS TIME 95 (2002).

46 WOLLMAN, supra note 15, at 199-200.

47 STEINER, supra note 20, at 137, 158-159; see also, JOHN W. STARR, JR., LINCOLN AND THE RAILROADS; A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY (1927).

48 FRANK, supra note 17, at 6-7.

49 BURLINGAME, supra note 6, at I:437-438 .

50 EMERSON, supra note 34, at 337; The Pullman strike involved volatile union, work condition and wage, race, immigrant labor and legal rights issues. See, SUSAN ELANOR HIRSCH, AFTER THE STRIKE: A CENTURY OF LABOR STRUGGLE AT PULLMAN 11-12 (2003).

51 Lincoln’s arguments to juries were to the common man in a way that the common man could comprehend his points. Frank, supra note 17, at 23; He enjoyed life on the circuit, where he enjoyed relating funny stories and antecedents to his fellow lawyers. BRIAN DIRCK, LINCOLN THE LAWYER 44-53 (2007).

52 See, GARRY WILLS, LINCOLN AT GETTYSBURG: THE WORDS THAT REMADE AMERICA 263 (1992).

53 HAROLD HOLZER & NORTON GARFINKLE, A JUST AND GENEROUS NATION: ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE FIGHT FOR AMERICAN OPPORTUNITY 80 (2015).

54 JAMES G. RANDAL, Lincoln the Liberal Statesman in LINCOLN’S AMERICAN DREAM: CLASHING POLITICAL PERSPECTIVES 43 (Kenneth L. Deutsch and Joseph R. Fornieri eds., 2005).

55 Lincoln not only personally wrote the Emancipation Proclamation, he vigorously advocated for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery and establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau that would give land and education to the freed slaves. RICHARD SRINER, FATHER ABRAHAM: LINCOLN’S RELENTLESS STRUGGLE TO END SLAVERY 246-248 (2006).

56 PAUL SIMON, LINCOLN’S PREPARATION FOR GREATNESS: THE ILLINOIS LEGISLATIVE YEARS 282 (1971).

57 MORTON J. HORWITZ, THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN LAW 1870-1960: THE CRISIS OF LEGAL ORTHODOXY 80-85 (1992); See generally, MATTHEW JOSEPHSON, THE ROBBER BARONS: THE CLASSIC ACCOUNT OF THE INFLUENTIAL CAPITALISTS WHO TRANSFORMED AMERICA’S FUTURE (1962).

58 STEINER, supra note 20, at 177.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine