Trial of a large damages case in a small, low-income county

If you intend to ask for a hundred million dollars, come clean about it upfront

Every trial lawyer succumbs to the realization that the night before you start trial is stressful. Undoubtedly, the nerves start to kick in. You spend half the night preparing for jury selection, reviewing pre-trial motions and fine-tuning your opening statement. You finally attempt to lie down in the hopes you can catch a few hours of sleep, but you can’t. A more pressing and critical problem exists, keeping you awake, tossing and turning. Imagine a situation where in a few short hours you will be in front of potential jurors in one of the smallest, poorest counties in the state, asking them to award your client millions – hundreds of millions – of dollars.

A daunting problem

This big-money problem is not a simple task but rather a daunting one. You have already sat through the mandatory settlement conference where the judge hammered you and your client, almost comically and joyfully, with the fact jurors in this county won’t grasp the concept of hundreds of millions. You review the verdict history and are disappointed as the highest verdicts in the history of the county barely exceed one million. More depressing, you are able to count on one hand how many times the one-million dollar threshold has been surpassed. The jury consultants whisper into your ear that nobody in the juror panel fits the profile desired for the plaintiff.

How on earth can you be expected to convince people who live at or below the poverty line to award more money than they could ever imagine? More money than all of the people in the courtroom combined could earn in their entire lifetimes?

Be professional

Starting with the obvious, you have to be yourself. You cannot cheat jurors by pretending to be someone you’re not. Don’t try to dress in a way you believe is more common and familiar to your possible jurors. If a large portion of your potential jury works on farms or ranches, don’t rent a Chevy truck to drive to the courthouse. Don’t waltz into the courtroom on the first day wearing cowboy boots or chewing tobacco. Prospective jurors see right through all the fluff and you have lost most, if not all, of your credibility before you ever utter a single word.

It is unreasonable to believe an individual or company with hundreds of millions on the line would hire a trial lawyer who acts like they just came from hanging out at the farm or ranch. The monetary stakes are high. Substantial risks and exposure exist for all parties. This type of litigation likely is going to be complex, fact- and document-intensive and hard fought. Your opposing counsel will be wearing a three thousand dollar suit, will be highly skilled and will mount a forceful and aggressive defense. You must act professional, confident and worthy of sitting at the counsel table in a significant and noteworthy trial.

You need to be confident in yourself and your abilities as a trial lawyer. Jurors can always sense nervousness or fear. Given the magnitude and impacts of the litigation, the jury is going to expect you to be prepared and on the top of your game. As soon as the trial starts, much of the focus will be on you. The jurors will watch your every move and also your reactions and expressions. The way you talk, walk and sit will be analyzed in great detail. There are no second chances when you are the lead trial lawyer in a case involving hundreds of millions.

Once the trial starts you will be forced to make split-second strategic decisions. Do you need to ask any follow-up questions? Should you really object to a particular line of questioning? It goes without saying; you will not have all of the requisite knowledge and information required to make strategic legal decisions at the time they must be made. Sometimes, as a trial lawyer, you are in the dark and have to shoot from the hip. This requires you to be poised, confident and never second-guess yourself.

It is equally critical that you also have confidence in the case itself. The way in which you speak about the case and your clients, particularly your tone of voice, will convey the confidence message. The jury must be able to see that you believe in what you are doing and that you are representing the “good guy.” If you don’t believe in your case and your own clients, rest assured the jurors won’t either.

Juror questionnaires

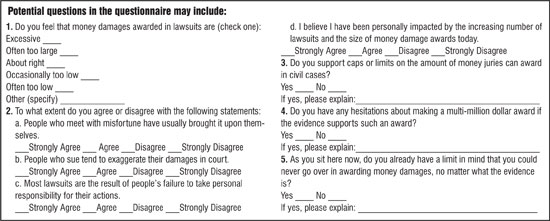

Your real task and challenge is to convince your jurors to comprehend the amount of money involved in the case. It is imperative to hit the jurors head-on early and often with the incredibly large amount of money being sought. You have to start conditioning the jury with the enormous money concept before you ever get a chance to speak to them. The use of juror questionnaires can prove to be a vital tool in attempting to get jurors more comfortable with the idea of eight-figure sums. Additionally, juror questionnaires can shed insight on which jurors may be favorable or unfavorable to your case. (See example on page 80.)

In addition to saving vast amounts of time during the jury selection process, the questionnaires provide a basic framework in which to narrow down possible jurors who seem likely to be more comfortable with awarding a large sum. Equally important, the questionnaires will provide an indicator as to which jurors you want to stay away from.

It is imperative you request the court to allow you to make a “mini-opening” statement prior to starting voir dire. California Code of Civil Procedure section 222.5 states in pertinent part: “The trial judge should allow a brief opening statement by counsel for each party prior to the commencement of the oral questioning phase of the voir dire process.” Don’t squander this opportunity to speak directly to the jury panel, as you will have limited chances to do so.

This is the point in time where you come clean and put all the cards on the table. You inform all possible jurors your client is seeking hundreds of millions of dollars in this action. The purpose in doing so permits jurors to begin becoming comfortable with the idea of such a large amount of money. The sheer amount of money subconsciously communicates to jurors that this is a major and important case with severe economic consequences. The hope is jurors will become enamored with the case and want to find out the detailed factual information and explanation as to why and how the damages being sought are so astronomical.

As you move to the jury-selection phase, you need to follow up with jurors regarding their answers to the damages’ portions of the juror questionnaires. Be very upfront and direct with jurors. Ask, “If plaintiff can prove that he or she suffered two hundred or even three hundred million in damages, would you be able to award that kind of money?”

Some jurors will be honest and tell you straight out there is no possible way they could award such a vast sum, regardless of what the evidence shows or the circumstances of the case. Sometimes the reason given by potential jurors is honest and simple. Potential jurors in the past have stated the following: “One percent of the money being discussed here could feed my entire family for generations” and “I refuse to make rich people richer.” While these are the types of responses plaintiff’s attorneys do not like to hear, it is necessary as it helps eliminate jurors who have a tendency to award lesser damages or those who find the thought of awarding large sums of money unpleasant and unnerving.

In addition to focusing on separating the possible high-dollar-verdict jurors from the rest, the jury selection process and the huge amount of money involved can be used to help make potential jurors feel like they have the chance to be part of something important – something greater than themselves. You want to leave jurors with the impression that this is a case they will always remember. The jurors need to feel that serving on the jury on this case will allow them to do something meaningful and leave a long-lasting impact in the community. This mentality will aid jurors in becoming committed to the process and more importantly, the case itself.

During your opening statement you must re-visit and mention the large dollars at stake. This sets the stage and tone for the trial. It’s inevitable that witnesses will refer to large-dollar figures in their testimony as the trial progresses. Jurors will hear over and over about huge sums of money. After a while, jurors will become so accustomed to hearing about tons of money, the shock factor decreases. Suddenly, tens of millions of dollars don’t seem like an outrageous sum. Maybe a few hundred million is okay in certain circumstances?

It will certainly take time for jurors to get used to the numbers being tossed around during trial. However, repetition is key to increasing the chances jurors will ultimately award your client the big money desired. By the time you arrive at your closing argument and you mention three-hundred million, the jurors are not stunned and dazed by the figure. If you have done your job well enough, you may be in line for a remarkable result.

In the end, the money involved is relative to the situation at hand. Jurors with simpler means realize, like the vast majority of us, that they don’t live in a world where hundreds of millions of dollars are commonplace. Yet, people are people, no matter what their background or financial status is. Following these simple suggestions can make it feasible to win record-setting verdicts in financially underprivileged counties.

Brian S. Kabateck

Brian S. Kabateck is a consumer rights attorney and founder of Kabateck Brown Kellner LLP. He represents plaintiffs in personal injury, mass torts litigation, class actions, insurance bad faith, insurance litigation and commercial contingency litigation.

Christopher Noyes

Christopher Noyes is an associate at Kabateck Brown Kellner with an expertise in litigating personal injury, class actions, insurance bad faith and business litigation cases.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine