Yes, you can mediate bad-faith cases

Understanding the level of misconduct and making an appropriate demand when the case is ripe for settlement

This article offers suggestions that counsel for insureds may consider to get the best results when mediating bad-faith cases.

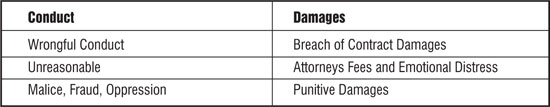

First, a quick review of the very basic elements of insurance bad faith: There are three levels of conduct in any potential bad-faith case and, as such, three different types of damages that can be obtained.

(1) wrongful conduct;

(2) conduct which is unreasonable and without proper cause; and

(3) conduct which is malicious, fraudulent or oppressive.

Wrongful conduct is merely the improper refusal to pay benefits and permits an insured to obtain only remedies due for breach of contract. In most cases, these damages are limited to the policy benefits.

Unreasonable conduct is bad faith. That permits an award of attorney’s fees and tort consequential damages, such as emotional distress.

The third level of conduct permits punitive damages. The chart below sets forth these concepts in simplified fashion.

With this in mind, there are a number of considerations for both counsel and their clients to consider when approaching mediation

What category of bad faith is your case?

Counsel representing insureds certainly prefer that their case falls in the third most lucrative category. It is, however, not normally the case. Punitive damages are actually awarded and retained in a very small portion of cases. Nonetheless, it is not uncommon for opening demands in mediation to include claims for punitive damages to see what the insurance company is going to do. Suffice for now to say that insurers are not exactly enthusiastic about settlement demands seeking punitives.

That is not to say that it is wrong to open with such a demand. But in order to reach closure, eventually the parties are going to have to meet someplace. If the case does not demand punitive damages in settlement, that reality is going to surface soon enough. Punitive damage claims are easy bargaining chips to trade in, but also easily ignored where not supported. The difficulty, of course, is where the insured starts off the mediation including a claim of punitive damages in the demand, only to drop the demand precipitously at some point to get into a realistic settlement range. As the damages vary depending on the character of the conduct, counsel and their clients are well advised to decide, realistically, which of the three categories their case really falls within. The next question is how supportable are the damages in each category.

Picking fruit

I have often described settlement as akin to picking fruit. If you pick fruit when it is ripe, it tastes sweet and delicious. If you try to eat fruit before it is ripe, it tastes sour and bitter. Cases settle when they are ripe for settlement. If one tries to settle a case before it is ripe, it may well leave a sour and bitter taste in one’s mouth. If the case isn’t ripe for settlement, then the parties have the choice to wait until it is ripe, or settle for a sum that will leave one with the feeling of having just taken a big bite out of a sour apple.

This principle is particularly applicable in bad-faith cases where the insured is seeking punitive damages. On very rare occasions, I have seen a punitive damage case settle early, but I emphasize rarely! When it comes to punitive damages, a good rule of thumb is that plaintiff’s counsel is going “to have to earn” them. There are many reasons for this, but let’s discuss two.

First, if a plaintiff is offered in settlement, full policy benefits and attorneys fees such that the plaintiff will net full policy benefits when the settlement is over, the risks of litigation demand careful consideration by both the attorney and the client. Insurers sometimes consider funds above and beyond that to be windfall money. This, of course, is not the case where there are substantial consequential damages or real punitive exposure.

Second, a summary judgment motion on punitive damages is a virtual guarantee. In the overwhelming majority of bad-faith cases, counsel representing the plaintiff should expect a motion for summary judgment and/or a motion for summary adjudication on the issues of bad faith and punitive damages. It is not uncommon for the parties to mediate when the motion is pending. It is uncommon for an insurer to settle a case involving a significant payment beyond the benefits and perhaps attorneys fees until either the summary judgment motion has been denied or the plaintiff has shown that he/she can present a truly persuasive case of bad faith or punitive exposure in the opposition to these motions.

In short, if counsel have concluded that the case realistically falls in the second or third categories, mediation out of the blocks has a low probability of success.

The bad publicity argument

I can’t begin to remember all the times I have heard the suggestion from a plaintiff or counsel that the insurance company is never going to want the publicity from a verdict in the case. It is, unfortunately, an argument that is unlikely to persuade the insurance company to pay more money. It does happen on occasion for unique reasons, but in the vast majority of cases, the refrain will fall on deaf ears.

The fact is that insurance companies have cases of all sizes, types and characteristics, often all over the country and the type of press that one case might receive just doesn’t move the needle. And for the most part, the press isn’t going to be interested in the case — unless it involves a celebrity or an extremely large sum. It’s better to stick to merits of the case.

Turning the cruise ship around

Insurance companies are mostly very large organizations. Unless forced to do so, they don’t move fast. It takes work and time to convince them of the merits of your case. Recall that the insurance company has already decided that the insured is not entitled to benefits because the reason for the lawsuit is that the claim was denied in the first instance. So the insurer needs to be convinced that it was wrong.

Frequently, meaningful facts or arguments come up shortly before or during mediation and insureds and their counsel would like to see the insurance company respond quickly to those new events. But insurance companies resemble in some fashion a large cruise ship. They are not built for speed. They simply can’t turn that fast. It takes time and effort to stop, turn around and head in the other direction. Cruise ships do turn around and head in the opposite direction, but they do so slowly and carefully. There are just times when the parties have to recognize that the ship is going to turn around, but it is going to take time.

Which leads to my next point.

Write your briefs for the in-house attorneys and adjusters

The submission of confidential mediation briefs, particularly by the defense is increasingly common. If the defense does not provide its brief to the plaintiff, then the plaintiff sometimes refuses to provide its brief to the defense. I think this is a mistake.

First, it is very often true that there is nothing really confidential in the defense brief. Sometimes the defense is simply being cautious. Sometimes, that is just the company’s procedure in all cases. Regardless, in order to settle a case, an insured needs to convince the person(s) with the checkbook, that a check needs to be written for a certain amount. Defense counsel may or may not have presented the insured’s case well to that person(s). The mediation brief is the insured’s opportunity to talk directly with the insurance company.

I encourage insureds and their counsel, as I did when I was practicing, to take the time to prepare a strong mediation brief and send it early to the defense, without concern of whether you receive a brief in return. Recall that insurance companies are like cruise ships and it takes a lot to get them to turn in your direction. And besides, the plaintiff is going to be laying out his/her case in detail in any event in opposition to the motion for summary judgment that will be arriving about 105 days prior to trial.

To get real money, the insurance company needs to be convinced that (1) the insured has the facts and the law and (2) that plaintiff’s counsel is willing and capable of presenting those facts effectively to a jury. A good mediation brief can be a sizeable down payment on these two goals.

Attorney’s fees and Cassim v. Allstate

Attorney’s fees incurred to collect the benefits of the contract, are recoverable if bad-faith conduct is established. Brandt v. Superior Court (1985) 37 Cal.3d 813. These fees are either presented to the jury during the trial or, by stipulation of both parties, to the Court after the trial. The Court in Brandt encouraged the parties to present them to the court post-trial, but it does require a stipulation from all parties.

A percentage of the benefits is the simplest claim for attorneys fees. When the benefits are small, counsel can claim that attorneys fees on the entire award are the fees that were necessary for the attorney to take the case. Cassim v. Allstate Ins. Co. (2004) 33 Cal.4th 780. However, Cassim includes a specific formula for how to calculate those damages.

I once made the mistake, like many attorneys, of not looking carefully enough at the specific Cassim formula. By the time one runs through the calculations required by Cassim, it is very likely that one will conclude that the attorneys fees capable of being claimed are so small that it may not be worth the effort.

A claim to legitimate attorneys fees is an important part of settlement negotiations. I would only caution that counsel makes sure they are, in fact, legitimate. If based on a calculation of fees and time spent, Cassim should be read with care.

Anticipate the genuine dispute doctrine

Appreciate insurer fondness for the genuine dispute doctrine. I can’t say the exact odds that the insurer will rely on the genuine dispute doctrine in its defense, but the chance is certainly quite high. It has long been the law that it is not bad faith for an insurer to take a legal position that turns out to be wrong, but which was a reasonable contention given the unclear state of the law at the time.

This “genuine dispute” doctrine was extended to factual situations in Chateau Chamberay Howeowners Assn. v. Associated Interna. Ins. Co. (2001) 90 Cal.App.4th 335. In that case, the claim was that the dispute was solely whether the insurance company’s expert or the insured’s expert was correct — a dispute the insurer contended was certainly “genuine.” The genuine dispute doctrine reached the California Supreme Court in Wilson v. 21st Century Ins. Co. (2007) 42 Cal.4th 713. Plaintiffs have interpreted Wilson as holding that there really is no genuine dispute doctrine. Either the conduct is unreasonable and thus bad faith or it is not.

A finding that there was a genuine dispute is, in fact, nothing more than a finding that the conduct under all of the circumstances of the case was reasonable. They cite the following. “[A]n insurer’s denial of or delay in paying benefits gives rise to tort damages only if the insured shows the denial or delay was unreasonable. Wilson, supra, at 723. “[W] find potentially misleading the statements in some decisions that under the genuine dispute rule bad faith cannot be established where the insurer’s withholding of benefits “is reasonable or is based on a legitimate dispute as to the insurer’s liability. [cites omitted]. In the insurance bad- faith context, a dispute is not “legitimate” unless it is founded on a basis that is reasonable under all the circumstances.” Id., at 724, n.7.

Insurers, however, claim that the genuine dispute doctrine continues to be a viable defense, particularly where the dispute is solely a question of which expert — the insured’s or the insurer’s — happens to be correct. And, in the very recent case of Paslay v. State Farm Gen. Ins. Co., 248 Cal.App.4th 639 (2016), the Court of Appeal held that “the bad-faith claim fails under the genuine dispute doctrine” and that summary judgment on bad faith was properly granted to the insurer. The holding was based on the insurer’s contention that it reasonably relied on its expert and that the insured prevented its expert from evaluating important aspects of the claim.

Arnold Levinson

For over 30 years, Arnie Levinson has assisted over 1,000 clients in coming to resolution. He has been routinely involved in shaping state and national legislation in insurance law. He was a founding partner at Pillsbury & Levinson, leaving after 20 years to bring his skills to the field of mediation. He has been a member of ABOTA; served as President of the San Francisco Trial Lawyers Association; and is a three-time recipient of the Presidential Award of Merit from Consumer Attorneys of California.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine