The emerging frontier of long-term-care-insurance bad faith

As the claims for baby boomers start rolling in, the denials are likely to start churning out

Bad-faith claims-handling by disability insurers has resulted in significant litigation for decades. But not so much in the long-term care context, at least so far. That is likely to change. In the same way that insurers in the 1980’s to early 1990’s scrambled to sell high-benefit disability policies that were poorly underwritten, carriers have recognized they did an even worse job of underwriting their long-term care products.

In the area of disability insurance, an explosion of claims led to bad-faith practices designed to shut down the claims, resulting in numerous punitive-damage verdicts and market-conduct examinations of carriers’ improper practices throughout the country.

Yet the same has not occurred in the long-term care context for one simple reason – the claims have not yet come home to roost. One leading long-term care insurer has privately determined that only 2 percent of anticipated claims of its in-force long-term care policies have yet been filed. And the amount of reserves – the money set aside to cover future claim payments – is expected to balloon to a staggering $15 billion over the next 15 years.

It is a must to have a detailed understanding of the long-term care insurance product and the common issues likely to be encountered in the representation of long-term care insureds when, as occurred in the disability context, the claims start pouring in and the denials start churning out.

The long-term care insurance product

In California, regulation of long-term care insurance is set forth at sections 10231 through 10237.6 of the Insurance Code. Generally, long-term care insurance is designed to cover a host of services and expenses that are not covered by regular health insurance when the insured suffers from a chronic medical condition, disability or disorder, such as dementia. (See, § 10231.2 (defining long-term care insurance as providing coverage for “diagnostic, preventative, therapeutic, rehabilitative, maintenance, or personal care services that are provided in a setting other than an acute care unit of a hospital.”).)

Most policies will provide a set daily benefit for reimbursement of expenses incurred for the following types of care:

Nursing home care: A facility that provides a full range of skilled health care, rehabilitation care, personal care and daily activities in a 24/7 setting.

Assisted living facilities: A residence with apartment-style units that makes personal care and other individualized services (such as meal delivery) available when needed.

Home healthcare: An agency or individual who performs services, such as bathing, grooming and help with chores and housework.

Home modifications: Adaptations, such as installing ramps or grab bars to make the insured’s home safer and more accessible.

Adult day care services: Programs providing health, social and other support services in a supervised setting for adults who need some degree of help during the day.

Care coordination: Assistance by a trained or licensed professional for determining needs, locating services and arranging for care. Policies may also cover the cost of training care providers.

Most long-term care policies trigger entitlement to benefits upon an insured suffering from cognitive impairment or being unable to perform two or more Activities of Daily Living (“ADLs”) without assistance. ADLs refer to the following:

- Bathing, including the act of getting into or out of a tub or shower safely;

- Continence, including the ability to perform associated personal hygiene;

- Dressing;

- Eating, including being able to feed oneself;

- Toileting, including being able to get on or off a toilet safely;

- Transferring, meaning the ability to move into or out of a bed, chair or wheelchair safely.

A typical insuring agreement reads something like this:

We will pay a benefit for each day of Facility Confinement in a Nursing Facility or Residential Care Facility.

Payment will be the actual daily Facility Confinement charges you incur, up to the Daily Benefit shown on the Benefit Schedule. Benefits are subtracted from the Total Maximum Amount Payable.

Eligibility for Benefit Payment – You will be eligible for benefit payment for Qualified Long Term Care Services if:

You are unable to perform, without Substantial Assistance, at least two Activities of Daily Living for an expected period of at least 90 days due to loss of Functional Capacity; or

You have a Severe Cognitive Impairment.

The policy’s Benefit Schedule will set forth the dollar amount of the daily benefit, the elimination period (the number of days expenses must be incurred before benefits become payable), the maximum duration benefits are payable including any maximum benefit caps, and the amount of inflation increases, if any.

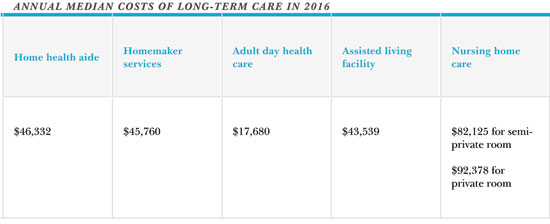

Many policies, particularly those sold in the 1990’s, often provide for unlimited lifetime benefits, with compound five percent annual COLA increases. For an insured suffering a chronic illness at a relatively young age, these policies can provide a significant amount of benefits. Further, the benefits provided are critically important and vital for the most vulnerable among us, typically the elderly who need home care assistance in order to remain home rather than being confined in a senior facility. And for the adult children of such insureds, securing benefits under a parent’s long-term care policy is critical to avoiding their own potential financial ruin. The median cost of long-term care in 2016, as estimated by a leading insurer, is staggering.

Challenges in securing benefits

Simply understanding the coverage requirements is challenging. As with any insurance claim, it is important to have a detailed understanding of the policy and its hidden traps, which are typically buried within the definitions section of a policy. But in the long-term care context, many of the definitions of the various covered long-term care services make it impossible to secure benefits without successfully wading your way through hidden licensing requirements for those prescribing or delivering the care. Consider the following definition of “Home Care Services” in one such policy, which incorporates many other defined terms that are single-capped:

Home Care Services is a program of medical and nonmedical services provided to ill, disabled or infirm persons through a Home Health Agency, including: Home Health Care providing professional nursing services by or under the supervision of a RN or other nurse; or therapeutic care services by or under the supervision of a speech, occupational, physical, or respiratory therapist licensed under state law, if any; or Homemaker Services; or Personal Care.

Post-claim underwriting

Post-claim underwriting is a particularly pernicious problem in the area of long-term care claims. Post-claim underwriting by insurers is certainly not new. It generally refers to the practice of rescinding or canceling coverage after submission of a claim based on an alleged misrepresentation by the insured in the policy application even though the insurer failed to complete underwriting before issuing the coverage. Such conduct exposes carriers to bad-faith liability. (See, Ticconi v. Blue Shield of Calif. Life & Health Ins. Co. (2008) 160 Cal.App.4th 528, 539-541 [post-claim underwriting may be enjoined as a violation of Unfair Competition Law where California law specifically forbids it].)

In all life insurance policies, and most disability policies, mandated “incontestability provisions” preclude insurers from seeking to rescind coverage based on application misstatements, including fraudulent misstatements, after a period of two years. In the area of long-term care insurance, however, carriers take the position that they have an unlimited amount of time to contest a policy based on an allegation the insured committed a knowing and intentional misrepresentation at the time of application. Although Insurance Code section 10232.3(f) specifies that the contestability period for long-term care policies shall be two years, it confusingly states, “as defined in Section 10350.2,” which pertains to disability policies and permits disability carriers to except fraudulent misstatements from a policy’s contestability limitation. This, they say, allows them to contest policies based on fraud no matter how long the insured dutifully paid premiums before having to submit a claim.

What is the end result of an open-ended contestability period? A full-blown investigation to find any possible misstatement on every claim submitted. A recent deposition of a carrier’s senior executive as to his company’s investigative procedures in this regard was quite stunning:

Q Does the phrase “post-claims underwriting” have any meaning to you?

A Yes.

Q And what meaning does it have to you?

A Companies that don’t underwrite at the time of underwriting and then conduct a much more robust medical records review after the fact are accused of performing post-claims underwriting.

Q So there must be some parameters in place at the company for when to conduct such an investigation, is there?

A No, it’s open ended. So it’s really a decision based on what we think the facts of that case might be.

Q So how do you advise the people at the company how to go about making that kind of decision?

A Well, essentially the claim adjuster is asked to refer on a case where they think the facts of the claim cause may have predated the application. So that’s the starting point. And then [the adjuster’s] level gives that more analysis and then moves it along if there’s a decision to be made.

Q Is that really the standard, though, that is, whether or not the cause may have predated the application?

A Well, in our line of business, because we get claims for things like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, conditions that have long incubation periods, it does happen regularly that we see a claim in this kind of time frame where the first records we acquire refer backwards prior to the application. So we feel we must investigate those situations.

Q So the company investigates all claims for possible contestability; is that right?

A We’re looking at that aspect every time for sure.

Q No matter how long the policy has been in issue?

A Yes.

To make matters worse, this particular company conducts such investigations in secret, blind-siding incompetent insureds and their family members with threats to rescind coverage. Such claim procedures are particularly abusive. By the time of claim, the insured may be incompetent and unable to adequately defend him or herself. Memories have faded. Contemporaneous medical records may be unavailable or require interpretation. Yet the treating physicians during the time of application may now be long since retired or dead.

Although carriers have the burden of proof to prove fraudulent misstatements by clear and convincing evidence (Ins. Code § 10232.3), that is no solace to an insured or her caregiver being served with a federal court lawsuit to rescind coverage.

An important limitation on a carrier’s ability to rescind coverage is set forth in section 10232.3(a). That subdivision provides:

All applications for long-term care insurance except that which is guaranteed issue, shall contain clear, unambiguous, short, simple questions designed to ascertain the health condition of the applicant. Each question shall contain only one health status inquiry and shall require only a “yes” or “no” answer, except that the application may include a request for the name of any prescribed medication and the name of a prescribing physician. If the application requests the name of any prescribed medication or prescribing physician, then any mistake or omission shall not be used as a basis for the denial of a claim or the rescission of a policy or certificate.

(Emphasis added)

Although no appellate authority has construed these limitations, the clear language of section 10232.3(a) should preclude carriers from seeking to rescind coverage, even for supposed fraudulent misstatements, on anything other than the simple “yes” or “no” questions to the applications. Often, carriers’ applications seek to elicit further information beyond that which is permitted under the statute, such as asking for the “full details” of any “yes” answer. Such application questions are improper and should not be allowed to form the basis of a subsequent rescission action.

Terry Coleman

Terry Coleman has been a partner with Pillsbury & Coleman, LLP (formerly, Pillsbury & Levinson), since 1999, specializing in the representation of policyholders in insurance bad faith and insurance coverage matters. He is a past president of the San Francisco Trial Lawyers Association and a Fellow of the American College of Coverage and Extracontractual Counsel. Mr. Coleman also served as chair of the Insurance Section of the Association of Trial Lawyers of America (now AAJ). www.pillsburycoleman.com.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine