Lawyer Lincoln’s trial tactics

How Abraham Lincoln developed his trial skills and prepared himself to persuade juries

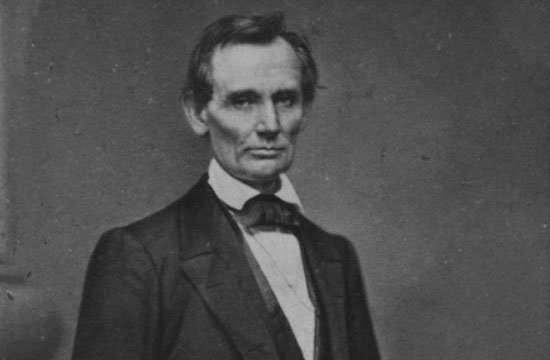

From his admission to the bar in 1837 and until he became president in 1861, Abraham Lincoln tried hundreds of jury trials. He was pretty good at it.1 Contemporary trial attorneys can learn a lot from reviewing some of Lincoln’s personal traits and talents that brought him success before juries.

In his early years as an attorney, Lincoln’s trials were mostly small cases tried on the rural judicial circuit where he had little time for preparation.2 Over the course of nearly a quarter century at the bar, his trial skills developed and he eventually was retained on a number of complicated cases requiring sophisticated trial strategies. To win for his clients, he could no longer “wing it,” as he had in many of the early matters that he picked up at county courthouses on the judicial circuit.3

Lincoln’s success was based on his exceptional diligence, power of concentration and focus on detail. The starting point for his winning trial strategy was gaining a command of the facts of a case and shaping them into a structure that told a persuasive story. He recognized that jurors are not impressed by the presentation of random evidence without a defined purpose. So digging into the facts was critical to prevail at trial.

Defending the railroad bridge

Lincoln’s trial methods depended on forming factual blocks of information that he molded into a clear, credible and forceful narrative. His methods are well-illustrated by his defense in the 1857 trial of Hurd v. The Rock Island Bridge Company, a case that symbolized a titanic clash of economic forces in the mid-19th century: modern rail was challenging traditional water transport and the burgeoning Chicago rail hub was pitted against the thriving St. Louis river port.4

The river-packet Effie Afton had struck the first railroad bridge across the Mississippi between Illinois and Iowa, damaging the vessel and burning the bridge. The ship owner sued the bridge company for obstructing the river with the bridge’s supporting piers, which he contended had caused the accident.

Abraham Lincoln was retained to defend the bridge company in a trial conducted before Supreme Court Justice John McLean, sitting in federal court in Chicago. With twenty years of trial experience under his belt, Lincoln was at his prime.

Lincoln spent months preparing to defend the bridge company. As an attorney who is the only United States president to hold a registered patent,5 Lincoln put his technical background and lawyer’s attention to detail to work investigating what had happened. He closely inspected the river at the collision site, measured currents and eddies to simulate accident conditions, interviewed witnesses about the crash, studied rail traffic and river navigation, and examined both the architecture and construction of the bridge. He also analyzed the policy argument that the railroad was the harbinger of the future and river carriers must accede to progress.6

Lincoln’s painstaking preparation formed a trial plan that was brought to a climax in his closing argument. According to an observer, “Lincoln’s examination of witnesses was very full and no point escaped his notice. I thought he carried it almost to prolixity, but when he came to his argument I changed my opinion. He went over all the details with great minuteness, until court, jury, and spectators were wrought up to the crucial points. Then drawing himself up to his full height, he delivered a peroration that trilled the courtroom and, to the minds of most persons, settled the case.”7 The jury split in favor of the bridge company. The case was finally resolved in the bridge company’s favor by the United States Supreme Court in 1862 after Lincoln had occupied the White House.8

Telling the story

Abraham Lincoln’s capacity to spin a yarn was well-recognized by those who knew him long before he determined to become a lawyer. He could sit around the proverbial cracker barrel and tell an entertaining or humorous story with the best of them.9 Lincoln’s great storytelling ability was rooted in his life experience, which he utilized to maximum advantage in beguiling juries. He used the age-old mechanism of storytelling to guide jurors, ease them into following the action and then lead them to his intended conclusions.

Lincoln knew that his mission was to build the facts of the case into a trial theme and a powerful story. Setting specific objectives and developing his trial plan around concrete facts, he avoided the jumble of witnesses and lack of organization that characterize some attorneys’ confusing approaches to trying a case. From the time that he entered a courthouse until the jury retired to deliberate, he pursued his singular goal of providing a simple and digestible narrative that pierced the heart of the controversy. How did he do this?

In preparing for trial, Lincoln “walked the walk” to ensure that every aspect of the trial conveyed a consistent message. Although most of his trials were in civil matters, an 1858 criminal matter, People v. Armstrong, dubbed the Almanac Case, exemplifies Lincoln’s courtroom skills at the height of his trial attorney prowess. Lincoln’s client Duff Armstrong was charged with bludgeoning a man over the head with a heavy lead “slingshot” weapon, killing the victim. The odds were long against Armstrong, who was the son of old friends, whom Lincoln represented as a favor without charging a fee. The defense was tough. A co-defendant had already been convicted in a separate trial and sentenced to prison.10

The prosecution’s main witness had testified convincingly that he had unmistakably seen Armstrong and his accomplice commit the grisly crime at night in the woods under an illuminating full moon. Undaunted by this strong adverse evidence, Lincoln personally interviewed witnesses and examined the crime scene from every angle. He then developed a trial plan based on an alternative version of the facts casting doubt on the eyewitness’s account.

Donning a pure white suit emblematic of his client’s innocence, Lincoln began the trial by ostentatiously handing an almanac to the bailiff in a manner that jurors could not miss. His intense cross-examination focused on how and what the eyewitness could see: Had he been close enough to see Armstrong swing the slingshot and crush the victim’s head? What did the co-defendant swing? Could the blows be seen clearly through the thick foliage? Was he absolutely certain that the moon was high in the sky over the crime scene? Was he totally sure that the moon was shining directly on down?11

Building a theory of the case through such questions intended to cast doubt on the eyewitness’s account, Lincoln doubled- down with extraordinary care to pin the man down to his version of the events. Lincoln then reached for the almanac, placed the published phases of the moon on the night in question before the witness and confronted him with the irrefutable fact that the moon was already setting at the time of the crime. Now was he sure of what he had testified? The witness could not respond further to Lincoln’s questioning. The prosecution’s case crumbled and the jury acquitted Armstrong.

Lincoln had accomplished his objective by presenting a plausible completing story with a defined structure that provided, factor after factor, how and why the eyewitness might have been mistaken. Through his tightly worded questions, he constructed a coherent narrative that kept the jury anxiously wondering how his cross-examination could overcome the facts seemingly stacked so high against the defendant. At the same time, he humanized his client by parenthetically mentioning his lifelong association with Armstrong’s family. His coup de grace, the conflicting physical evidence of the almanac entry, clinched the defense.

Lincoln’s story-of-the-case in the Armstrong trial was not a boring pile of miscellaneous information, unexplained disparate events, disconnected or dud witnesses, an incoherent “jigsaw puzzle” or confusing “roadmap” that left jurors without direction. His every action was aimed at creating tension and conflict that compelled jurors to listen and follow along. By relating a purposeful story that made sense, he cast doubt on the prosecution’s case and gave the jurors the ammunition to reach their own decision to acquit his client.

Simplicity in presentation

Lincoln did not hesitate to look jurors right in their eyes and, straight-forward and without exaggeration, tell them exactly what he wanted them to do. One colleague commented that, “Clarity, conciseness, and simplicity of statement were his forte in the trial of a case. His mind was orderly. He could marshal facts in such an orderly sequence and reduce a complicated problem to such simple terms that even the dullest layman could not fail to understand.”12

Lincoln’s advocacy was more than just style. He had a substantive approach to examining witnesses.13 To the greatest extent possible, he attempted to pose questions that had no fat on the bones. His specific and lucid questions were bullets that shot to the heart of the case. Central to his approach was ensuring that his questions were carefully selected to fit into a structure that proved the case, not superfluous inquiries that did no more than pile on non-essentials.14 By cutting through the clutter and focusing on what really mattered, Lincoln avoided turning a trial into a mess of incomprehensible contentions, lawyer histrionics or distracting bombast.

Flexibility in the heat of a trial is paramount. As a master trial tactician, Lincoln had a sixth sense to know when the sands of trial testimony were shifting against him and how he needed to adjust his strategy. When exigencies occur in trial, some attorneys mindlessly stick to their preconceived trial plans or obliviously drone on with pre-prepared questions despite altered circumstances. Lincoln, on the other hand, was alert to diagnose difficulties and react to remedy them.15

Where many lawyers would raise an objection or minor technicality “for the record,” Lincoln often would let a point pass without protesting. If a point did no great harm to his overall strategy, it was not uncommon for him to let it go by saying no more than he “reckoned” it would be “fair to let this in or that” or “admit the truth” to the inconsequential.16 As one attorney said, “By giving away six points and carrying the seventh he carried his case, and the whole case hanging on the seventh, he traded away everything which would give him the least aid in carrying that. Any man who took Lincoln for a simple-minded man would soon wake up with his back in a ditch.”17

Lincoln’s direct appeal to jurors without beating around the bush is especially well demonstrated by his representation of an elderly Revolutionary War widow who had been swindled by a government agent who greedily took half of her pension as a “fee” for his services. The indignant Lincoln aimed to do justice for the cheated old woman.

He began his pretrial prep by brushing up on his Revolutionary history. He then sketched an uncomplicated outline of a trial strategy that offered an appeal to the jurors’ common sense, patriotism and sympathy. His trial notes went straight to the point: “No contract – not professional services – unreasonable charge – money retained by Defendant not give to Plaintiff – Revolutionary War – Describe Valley Forge privations – Ice – Soldier’s bleeding feet – Plaintiff’s husband – soldier leaving home for army – Skin defendant! Close!”

Rising to present his closing, Lincoln calmly stated in a slow, sad voice, “Time rolls by; the heroes of ‘seventy-six’ have passed away and are encamped on the other shore. The soldier has gone to rest and now, crippled, blinded, and broken. His widow comes to you and to me, gentlemen of the jury, to right her wrongs. She was not always thus. She was once a beautiful woman. Her step was elastic, her face as fair . . . But now she is poor and defenseless . . . she appeals to us who enjoy the privileges achieved for us by the patriots of the Revolution, for our sympathetic and manly protection . . . All I ask you is, shall we befriend her?”18

It did not take long for the jury to agree with this plain-speaking appeal.19 Not surprisingly, this heart-rending entreaty was effectively issued by the lawyer who would later deliver the brief, 272-word Gettysburg Address and a concise, six-paragraph Second Inaugural Address beseeching the North and South to bind their wounds at the end of a brutal Civil War.20

Plain words, no legalese

Every trial attorney has been told again and again: “Don’t talk down to people by using complicated, highfalutin and technical language. Use common words that regular people understand.” Unfortunately, some counsel cannot restrain themselves; their legal mumbo-jumbo seems to roll out naturally. Not Abraham Lincoln. He used the language and talked the talk of the common folk who understood his voice.

Lincoln appreciated that his ability to persuade jurors depended on communicating in ordinary language that his audience could easily follow. Legalese and “nickel” words were foreign to him. No high-toned expressions came forth from country lawyer Lincoln, thank you. On one occasion when an attorney used a Latin term in court, the man turned to Lincoln and inquired, “That is so, is it not, Mr. Lincoln?” Lincoln replied, “If that’s Latin, you had better call another witness.”21

Unlike some trial lawyers then and now, Lincoln possessed a natural knack to convey his message to the jury wrapped in homespun wisdom without a lot of pomp and pretense.22 His keen sense of humor and ability to turn awkward situations on end with comedy were well-known.

In one trial that was not going too well, he had trouble fashioning a defense. Putting his knowledge of rural jurors to work, Lincoln happened to notice that the opposing attorney was wearing an outlandish shirt with buttons both down the back and front mimicking a then-current foppish British fashion. Perfectly reading his country audience, Lincoln swung the jury to his side with a ridiculing closing remark, “Counsel has pretended knowledge of the law, but as he has his shirt on backwards, he has his law backwards.” The jury burst out laughing at Lincoln’s mockery and found for his client.23

Lincoln had an uncanny gift to work with words to add wit to his presentations.24 A fuddy-duddy judge kept correcting Lincoln’s pronunciation of the word “lien,” which Lincoln pronounced “lean.” The judge kept telling Lincoln that it should be “lion.” After a while, Lincoln went back to pronouncing it in his own way and was corrected a second time by the court. Lincoln apologized, “As you please, your honor.” He soon slipped once again and the court warned him. Lincoln replied that, “If my client had known there was a lion on his farm, he wouldn’t have stayed there long enough to bring this suit.”25

Creating visual images

Lincoln knew that his job in the courtroom was to create an emotional atmosphere through words and other aids that paint pictures with which jurors could plausibly identify. If he was succeeding, his well-presented narrative would sketch a familiar scene or open a window in the listener allowing for a shared experience leading to an accepted message. He appreciated that if he did no more than lay out bare facts through bland, unanimated testimony, even his highly effective forensic skills would fall flat on a disinterested audience.

For these reasons, he honed his natural ability to advocate like a lawyer without looking and sounding like one. Using images to make jurors eyewitnesses to the case, he got beyond jurors’ natural skepticism that they were being sold a bill of goods. His goal, as every good trial advocate knows, was to make the jurors into witnesses and participants to the events comprising the trial.

The imagery projected by Lincoln began with his own physical appearance. At six feet and four inches tall, in a time when the average man was eight inches shorter, he typically arrived at a courthouse in a black ill-fitting suit, topped by a stove-pipe hat that reached to the sky and carrying a broken umbrella fastened around with a piece of string. His sallow facial features were marked by high cheekbones, large deep-set greyish brown eyes shaded by heavy eyebrows accenting a grim, determined look on his craggy, melancholy face. Jurors could not ignore his squeaky, high-pitched voice, and gangling arms stretching down to his oversized hands and long slender fingers.26

While some swear that humor has no place in a courtroom, Lincoln knew how to strategically use a little laughter to his advantage. His keen sense of self-deprecating humor usually allowed him to get around his ungainly appearance. But his use of humor for advocacy purpose went beyond occasionally making fun of his appearance at his own expense. When the circumstances permitted, he deftly employed parody, satire and sarcasm to drive home the righteousness of his client’s case or deflect an opponent’s position.27

An instance of Lincoln’s skill in this regard occurred during the cross-examination of a high-priced doctor, a key witness in a circumstance where Lincoln’s defense seemed tenuous. As was his custom in many trials, Lincoln passed on examining the plaintiff’s witnesses until the linchpin expert was called. He went directly to revealing his defense strategy by inquiring, “Doctor, how much are you to receive for testifying in this case?’ The witness asked the judge whether he had to answer the question. The judge acknowledged that the question was within bounds and ordered a response. The expert’s fee was such a high amount that it stole the jurors’ breaths. In closing, Lincoln wagged his boney forefinger at the jury and, in his shrill voice, ridiculed the doctor’s credibility by calling his outlandish fees into question, “Gentlemen of the jury, big fee, big swear!” The jury was won over through Lincoln’s exclamation undermining the doctor’s testimony and a favorable verdict was returned for his client.28

The power of persuasion

Lincoln, of course, could neither read jurors’ minds nor was he capable of mental telepathy. But he understood that it is the trial attorney’s job to get into jurors’ heads by creating a conversation with them, repeatedly focusing attention on the merits of the matter, and, finally, providing the means to enable jurors to figure out the case on their own in the jury room.

Some of Lincoln’s contemporaries believed that he had success as a trial lawyer because he could do all of these things with great facility. He was described by one of his best boosters as the “strongest jury-lawyer we ever had in Illinois . . . who could make a laugh, and, generally, weep at his pleasure” who was a “quick and accurate reader of character . . . [who] understood, almost intuitively, the jury, witnesses, parties, and judges, and how best to address, convince, and influence them;” and “an admirable tactician” who skillfully kept the jury on track toward his objectives.29

Lincoln’s ultimate aim was to gather together the facts, apply logic and common sense, and then, through his closing argument, urge jurors to commit to his position during their deliberations. In closing, he was at his pinnacle of persuasion. By the end of a trial, he usually had what he needed for argument. Without pounding on the table, losing his temper, bullying or strutting about, he could move jurors with a low-key logical plea premised on the facts and justice of the case, not mere emotionalism.30

Nineteenth century biographer Noah Brooks may have laid it on a little thick when he stated that, in speaking to a jury, Lincoln rose to “twenty feet high” and “no longer was the homely and ungainly man that he was reputed to be. His eyes flashed fire; his appearance underwent a change as though the inspired mind had transformed the body; his face darkened with malarial influences and seamed with wrinkles of premature age transfigured with the mysterious ‘inner light’ which some observers have said reminded them of a flame glowing with a half-transparent vase.”31

Notwithstanding such hyperbole, many of his contemporaries agreed that he was a “jury man” who had a substantially better command of rhetoric and elocution than most lawyers of his day and he worked hard to perfect trial skills that might even turn a sow’s ear of a case into a winner.

Honesty above all

Abraham Lincoln strived to maintain high moral and ethical standards in representing his clients. His trial lawyer’s toolbox necessarily included diligent efforts to create credibility, develop trust, exhibit fairness, show courtesy and, at the same time, display an appropriate level of passion with and for his clients. He seldom allowed his trial techniques, personal emotion or identification with a client’s case to interfere with his absolute sense of integrity or professional responsibilities.32

Lincoln was called “Honest Abe” by his colleagues at the bar for good reason.33 Recognizing that false or insincere arguments are easily detected, he attempted to speak with moral conviction. He did his best to be honest and maintain integrity with judges and juries by calling trustworthy witnesses who told the truth, avoiding misrepresentations of facts and never offering underhanded cross-examination.34

In an era long before lawyers typically offered representation on a pro bono basis, Lincoln was not a knight-errant who took on causes for clients. But “doing the right thing” was foremost to him, as demonstrated by him representing Duff Armstrong in the Almanac Case for gratis based on his longstanding friendship to the family. Indeed, in his closing argument in that case, he violated his general rule against injecting personal emotions into the case when he related his past relationship with the defendant’s family.35

Although typically reserved, Lincoln also could show his human side. He represented an elderly woman charged with killing her husband in self-defense. At a trial recess, she fled by stepping out a courtroom window. When the bailiff pointed to Lincoln’s complicity, he responded, “I didn’t run her off. She wanted to know where she could get a good drink of water, and I told her there was mighty good water in Tennessee.”36

Lincoln’s method of confronting ethical dilemmas that arose during trial sometimes caused him great pain. His sense of moral righteousness would not allow him to continue to represent a client whom he decided was in the wrong or untruthful. During a murder trial, he concluded that his client had no defense and was not innocent. He withdrew, stating that “I cannot argue this case because our witnesses have been lying, and I don’t believe them.”

Similarly, when representing the plaintiff in a collection matter, he absented himself from the courtroom during the trial when the evidence contradicted his client’s position. The bailiff came to bring him back. He refused to return, complaining, “Tell the Judge that I can’t come – my hands are dirty and I came over to clean them.” The judge dismissed the case, commenting with but two words that defined the situation, “Honest Abe.”37

Every attorney practicing law today knows the ethical precept that a lawyer should not assert or defend a claim or argument in a civil or criminal proceeding unless there is some basis in law and fact for doing so.38 Lincoln explicitly followed this admonition long before it was promulgated as an ethical canon by the bar.

One lawyer observed, “It was morally impossible for Lincoln to argue dishonestly. He could no more do it than he could steal.”39 Another commented on how Lincoln put his straight-arrow honesty into practice in the courtroom: “If a witness told the truth without evasion, Lincoln was respectful and patronizing to him, but he would score a perjured witness unmercifully.”40

Lincoln’s ethical message

Abraham Lincoln himself had this enduring advice regarding honesty and ethical conduct in the practice of law: “There is a vague popular belief that lawyers are necessarily dishonest. I say vague, because when we consider to what extent confidence and honors are reposed in and conferred upon lawyers by the people, it appears improbable that their impression of dishonesty is very distinct and vivid. Yet the impression is common, almost universal. Let no young man choose the law for a calling for a moment yield to the popular belief – resolve to be honest at all times; and if in your own judgment you cannot be an honest lawyer, resolve to be honest without being a lawyer. Choose some other occupation, rather than one in the choosing of which you do in advance, consent to be a knave.”41

Michael L. Stern

Judge Michael L. Stern has presided over civil trial courts since his appointment to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 2001. He is a frequent speaker on trial practice matters. As an attorney, he tried cases throughout the United States. He is a graduate of Stanford University and Harvard Law School.

Endnote

1 MARK E. STEINER, AN HONEST CALLING: THE LAW PRACTICE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 75-100 (2006). [STEINER].

2 In the frontier days in developing Illinois in the early and mid-19th century, the state was divided into judicial circuits. The Eighth Judicial Circuit included fourteen counties around Springfield, where Lincoln had his offices. He would travel to the county courthouses with the judge and fellow attorneys and pick up cases referred by local attorneys. WILLIAM H. HERNDON AND JESSE W. WEIK, HERNDON’S LIFE OF LINCOLN: THE STORY OF A GREAT LIFE 2:309-311 (1888). [HERNDON]. See generally, GUY C. FRAKER, LINCOLN’S LADDER TO THE PRESIDENCY: THE EIGHTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT (2003).

3 In the beginning. Lincoln’s law practice revolved around litigation about everyday matters typical to a rural agrarian economy, such as disputes over title to property, debt collection, small contracts, personal injuries and domestic matter of all kinds. He also tried a fair number of criminal cases, but, for the most part, stuck to civil cases. LAWRENCE WELDON, “Leader of the Illinois Bar” in ALLEN THORNDIKE RICE, REMINISCENCES OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN BY DISTINGUISHED MEN OF HIS TIME 128 (1885). [WELDON].

4 RONALD C. WHITE, JR., A LINCOLN: A BIOGRAPHY 241-244 ((2009). [WHITE]. See generally, LARRY A. RINEY, HELL GATE ON THE MISSISSIPPI: THE EFFIE AFTON TRIAL AND ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S ROLE IN IT (2006) [RINEY].

5 WHITE, supra note 4, at 162-163.

6 ALBERT A. WOLDMAN, LAWYER LINCOLN 182-184 (1936). [WOLDMAN].

7 FREDRICK TREVOR HILL, LINCOLN, THE LAWYER, 260-261 (1906)

8 WHITE, supra note 4, at 244. Lincoln’s victory in the Effie Afton case has been called the biggest success in his legal career. HAROLD HOLZER AND NORTON GARKINKLE, A JUST AND GENEROUS NATION: ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE FIGHT FOR AMERICAN OPPORTUNITY 22 (2015).

9 Lincoln’s longtime partner William Herndon commented that “[i]n the role of story-teller I am prone to regard Mr. Lincoln as without an equal.” HERNDON, supra note 2, at 2:309-311. See, e.g., P.M. ZALL, (ed.) ABE LINCOLN’S LAUGHING: HUMOROUS ANECDOTES FROM ORGINAL SOURCES BY AND ABOUT ABRAHM LINCOLN (1995).

10 There have been many accounts of the Almanac Case and Lincoln’s trial strategy, cross-examination and closing argument in the trial. See, e.g., ALLEN D. SPIEGEL, A. LINCOLN ESQUIRE: A SHREWD, SOPHISTICATED LAWYER IN HIS TIME 157-158 (2002). [SPIEGEL]. See also, JOHN EVANGELIST WALSH, MOONLIGHT: ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE ALMANAC TRIAL (2000).

11 WOLDMAN, supra note 6 at 122-123.

12 Id. at 205.

13 Lincoln would have readily recognized the “Ten Commandments of Cross-Examination” advanced more than a century later by Professor Irving Younger: 1. Be Brief; 2. Ask Short Questions in Plain Words; 3. Never Ask Anything But A Leading Question; 4. Ask Only Questions to Which You Already Know the Answers; 5. Listen to the Answer; 6. Do Not Quarrel with the Witness; 7. Do Not Permit A Witness on Cross-Examination to Simply Repeat What the Witness Said on Direct Examination; 8. Never Permit the Witness to Explain Anything; 9. Avoid One Question Too Many; 10. Save It for Summation. ROBERT E. OLIPHANT (ed.), TRIAL TECHNIQUES WITH IRVING YOUNGER 50-53 (1978).

14 JOHN P. FRANK, LINCOLN AS A LAWYER 96 (1961).

15 Id. at 170.

16 HENRY CLAY WHITNEY, LIFE ON THE CIRCUIT WITH LINCOLN 231-232 (1892). [WHITNEY].

17 Id. at 232.

18 HERNDON, supra note 2, at 2:340-342.

19 WOLDMAN, supra 6, at 241-245.

20 See generally, GARY WILLS, LINCOLN AT GETTYSBURG; THE WORDS THAT REMADE AMERICA (1992); JOSEPH R. FORNIERI (ed.), THE LANGUAGE OF LIBERTY: THE POLITICAL SPEECHES AND WRITINGS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 696-698 (2003).

21 ALEXANDER K. McCLURE, LINCOLN’S YARNS AND STORIES 122-123 (1901). [McCLURE].

22 FRANCIS FISHER BROWNE, THE EVERY-DAY LIFE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 235-236 (1887). [BROWNE].

23 McCLURE, supra note 21, at 69.

24 WELDON, supra note 3, at 133 (“Lincoln’s resources as a story-teller were inexhaustible and no condition could arise in a case beyond his capacity to furnish an illustration with appropriate anecdote.”).

25 McCLURE, supra 21, at 122-123.

26 Partner Herndon summed up Lincoln’s appearance that “[h]e was not a pretty man by any means, nor was he an ugly one; he was a homely man, careless of his looks, plain-looking and plain-acting.” HERNDON, supra note 2, at 3:588. It was said that Lincoln projected an aura of “a rough intelligent farmer.” BRIAN DIRCK, LINCOLN THE LAWYER 102 (2007).

27 WARD HILL LAMON, RECOLLECTIONS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 1847-1865 16 (1895).

28 EMANUEL HERTZ, LINCOLN TALKS: A BIOGRAPHY IN ANCEDOTE 26-27 (1939).

29 Attorney Issac N. Arnold, quoted in MICHAEL BURLINGAME, ABRAHAM LINCOLN: A LIFE 316 (2008). [BURLINGAME].

30 WOLDMAN, supra note 6, at 131.

31 NOAH BROOKS, ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE DOWNFALL OF SLAVERY 130 (1894).

32 WOLDMAN, supra note 6, 197-199.

33 One version how Lincoln gained the sobriquet “Honest Abe” was for the respect that he earned from his friends for his honor and honesty in paying off his debts of a failed store that he ran with a partner in the days of his youth in Old Salem before he moved to Springfield and later became a lawyer. KENNETH J. WINKLE, THE YOUNG EAGLE: THE RISE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN 100-101 (2001). Judge Samuel C. Parks, who practiced as an attorney in the courts with Lincoln, said that Lincoln was well known for his consistent honesty with clients, counsel and the courts. ALBERT J. BEVERIDGE, ABRAHAM LINCOLN 1809-1858 1:542 (1928).

34 BROWNE, supra note 22, at 142-143.

35 STEINER, supra note 1, at 13.

36 SPIEGEL, supra note 10, at 141.

37 BURLINGAME, supra note 29, AT 321.

38 See, AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIAITON MODEL RULES OF PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT, R. 3.1, Meritorious Claims and Contentions (2002).

39 WHITNEY, supra note 16, at 261.

40 Id.

41 DANIEL W. STOWELL (ed.), THE PAPERS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN: LEGAL DOCUMENTS AND CASES 1:12 (2008).

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine