Proving injury and damages in invisible-injury cases

Just because you can’t see the injury does not mean it’s not there. In TBI cases, with the right tools, you can bring that injury to light

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, at the end of this trial I am going to ask you to sign your name to a verdict form awarding 20 to 30 million dollars to my client, who by all accounts, looks, talks, and walks like a perfectly normal person.”

I recently had the honor of making that exact mini-opening to about 180 potential jurors in Department 1 of the Historic Courthouse in Riverside. That mini-opening highlights the challenges associated with invisible-injury cases – cases where we typically ask for large sums of money for clients who appear completely normal. In this article, I address some of the strategies that I have used to make these injuries come to light.

Over the last three years I have tried, and prepared for trial, multiple TBI cases. I believe that TBI cases are some of the most challenging cases out there. To make matters worse, most of my clients typically fall fairly low on the socio-economic ladder. As such, they rarely have the types of jobs that can be hampered by neurocognitive deficits. Thus, most have minimal loss of earning claims. And, most early treatment of TBIs does not involve significant medical costs. These two factors therefore make the future medical care and the non-economic damage portions of any verdict very important.

Building your future medical care case

Medical management of a TBI case sets the foundation of any future economic damage presentation. In a case where you have a concrete injury – like a broken leg or injured spine – the client will treat that injury, and based on the results, a doctor or life-care planner will opine that future treatment will be needed. Typically, that treatment is meant for years down the line.

In most TBI cases, any meaningful life-care plan will include:

- Case management;

- Psychotherapy;

- Neurocognitive rehabilitation;

- Counseling;

- Medication;

- Follow-up by neurologist and other medical professionals;

- Activity of daily living assistant, etc.

Typically, the life-care planner will have met with the client to do his or her evaluation and as such, will have knowledge of these needs long before your trial (be particularly aware of cases where long continuances are granted after the life-care plans are disclosed). But in most cases, the life-care plan is never brought to life and is used solely at trial to shore up your damages. Yet, any life-care planner or doctor will readily admit that the client would benefit from all of this treatment immediately.

Therefore, it is of vital importance to your case that you bring that life-care plan to life as much as possible before your trial – so that your life-care planner, or your client, or any doctor, can comment on how the client is already receiving the services that he or she so desperately needs and how that is benefitting him or her. This gives your life-care plan and your client a tremendous amount of credibility.

Understandably, this can raise the cost of the case, but it transforms the life-care plan from a theoretical document into a real-life “how-to” book on how to build a prosthetic environment for your client.

Get to know your client

Invisible injuries are difficult to convey because most of us typically don’t even know how they really affect our clients – yet that is the best source of information. And if we don’t really know them and their problems, how can we communicate it to 12 people who have their own problems? I have made a habit of participating in psychodrama sessions in all of my invisible-injury cases. Now, psychodrama is one tool – not the only tool. Some programs out there offer witness preparation sessions that serve similar purposes – which comes down to really understanding your client’s story from their perspective.

And although I find it helpful to enlist professionals to help in this process, there are many other ways to get the same results. Go spend a couple of days with your client and his family. Go have periodic meals with your client. I once went to dinner with one of my clients and got to see first-hand how he would completely “zone-out” and look blankly into space. I used that in my presentation. Go meet with their family outside of the client’s presence, preferably in their home. Look at the pictures or which scriptures are on the wall. That will tell you a lot about them and give you ideas for trial.

Although I always put at least one family member on the stand, I find that friends or colleagues are more detached and, as such, bring more credibility. If your client has friends or colleagues that they are, or were, close to – go visit them. For the last case I tried, I flew out of state to meet with three of my client’s co-workers to understand better how his injuries affected his social and work life. One of those witnesses came to testify for us and the jury found him very credible. One of the benefits of these types of witnesses is that the defense attorneys typically don’t depose them and therefore have no idea what they are going to say at trial. More importantly, they inevitably have no information to contradict what these individuals say. This allows you to make arguments at closing that the defense has presented zero evidence to challenge your non-economic damage presentation.

Get the right experts

Invisible-injury cases depend a lot on the quality of your experts. In nearly all of these cases, the most important currency you and your client have is credibility. I cannot stress this enough. If you or your client come across as manipulative or exaggerating in any way, it does not matter what evidence you produce – the jury will not believe you. This extends to the experts. TBI cases typically involve at least four or five experts. I like to use a neurologist, a psychiatrist, a neuropsychologist, a neuro-radiologist, and a rehabilitation expert. It is important that each of these experts understands the need for continuity of care of your client and that their opinions not contradict each other. The difficult part is to do that while maintaining each expert’s independence. This requires a lot of communication and preparation.

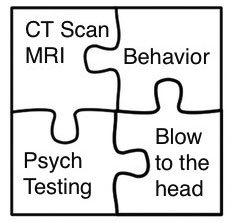

One of the most powerful points that you can make in a TBI case is that all of the evidence lines up – independently. The physiological damage to the brain matches the neuropsychological testing which matches the CT scans or MRIs, which matches what the family and friends have noticed about your client. I often use the following slide in my presentations to make this point (see page 43).

Use demonstrative exhibits and language

Invisible-injury cases benefit from a lot of demonstrative exhibits. Use actual CT scans, actual MRI scans, animations of the brain and the affected areas, animations of the accident to show the force of the impact, crash test videos, or anything else you have to demonstrate the force and effect of the impact. Also, make sure your experts use language that jurors can understand and that they relate the injury to everyday problems. It is one thing to talk about problems with executive functioning and quite another to say that he will never again be able to balance his checkbook. Or, telling a jury that an impact produced 200Gs of force to the head says very little, but explaining that most NFL concussions happen at 100Gs makes it more relatable. Find ways to use analogies and words that convey images in the jurors’ minds as much as possible.

I start using imagery in my opening in the way that I explain how the different parts of the brain work together. I have a few simple slides that depict the various areas of the brain that are essentially objection-proof. It’s effective in two ways: First, it explains the brain’s functions in a very visual and understandable way. And second, I start off the trial in the role of the teacher.

Explain the life-care plan

The life-care plan is one of the most important exhibits you will discuss at trial for an invisible-injury case. It also happens to be the most likely exhibit you will never get admitted. Most defense counsel will object vociferously to keep it out. They do that because they know that it is a very powerful document. It is therefore important that your life-care planner go over each of the categories of care one by one and explain (1) whose opinion it is based on and (2) why it is necessary. This is oftentimes a long and seemingly boring direct examination, but it is vital to your case. Only by explaining each of the categories can your expert gain credibility as to what will be needed.

Also, make it clear that this care is for the future and that it is not for your client to spend however he or she wants. One of the things that I emphasize on closing about the life-care plan is that the total value of it needs to be put in a lock box and invested or the client will never have enough money to make it all happen. This is a key part of the life-care plan and most life-care planners will include a requirement for legal fees for the establishment of a special needs trust.

Once the life-care plan has been laid out, the economist can address each category of care line by line and correspond the present value associated with it. Again, I always make sure that I emphasize the investment nature of the present value to make it clear to the jury that this money needs to be set aside. In nearly all of my TBI trials I have been able to get 100 percent of my life-care plan and I generally believe that if you properly prove the injury, most juries will give it to you.

Non-economic damages

This is the Holy Grail of invisible-injury cases. How does one convert the realities of living with a traumatic brain injury into a number? Unfortunately, there is no recipe for this and different lawyers might have different advice. I believe that the ability to get high non-economic damages stems directly from how credible and how trustworthy I am. I believe this is the case because at the end, lawyers are the ones who are suggesting numbers.

First, I think it’s important to let your jury know the severity and the extent of what you are going to ask for at the end of the trial. With the new amendment to section 222.5 of the Code of Civil Procedure, most judges will now allow a mini-opening as a matter of right. Use that opportunity to set the stage for what you are going to ask at the end of the trial. Generally speaking, I believe that the mini-opening should be used not to put your best case forward, but rather to lay out the issues you will be talking about during voir dire, which includes non-economic damages and any other “bruises” your case might have. Save your best points for the opening. If need be, file a motion in limine asking the court to allow you to bring up specific numbers during voir dire. Additionally, bring a motion in limine to allow the use of demonstrative slides during opening if need be.

Once you have established what you will be seeking during your mini-opening, you must become the most credible person in the room. This starts with jury selection. Everyone has to have their own style, but no matter what, you must be authentic. Don’t try to obviously pre-condition, don’t try to ingratiate yourself with the jury, don’t play into any of the lawyer stereotypes. Be real and authentic and ask the questions that you need to ask to ensure an impartial jury.

On opening, focus on the acts of the defendant first. There are many books on that topic and I will not repeat their strategies here. What I personally try to do is to find one sentence that encapsulates the wrongful acts of the defendant in the fewest words. Make it a statement that no one can disagree with. Do not argue. Do not overpromise. Do not say a single thing that cannot be proven. Also, acknowledge the problems that you have in your case. Level with the jury and do not let them hear about your bruises from the other side.

During trial, object sparingly and only when it matters. Show the jury that you are the most prepared lawyer. If you use outlines on direct, type them and print them and put them in a binder. Be ready to call your exhibits. When directing witnesses, cut right to the chase and get them in and out. Don’t waste the jury’s or anyone else’s time. Find areas of agreement between the defense experts and your side of the case and write them down on a board. Be kind to the defense experts that agree with you and attack those who are clearly unreasonable.

During closing, be honest about what the evidence showed. If some of your witnesses did not perform all that well, mention it and address it. Similarly, if some of the defense experts resonated with you, there is a good chance they resonated with the jury as well, so address it. The point is that you want to mirror what the jurors already think. That is real credibility.

Address non-economic damages head on. I think it’s wise to break up the 10 categories of non-economic damages and list the ones that apply and omit the ones that don’t. Again, it’s all about being credible. When a category applies, discuss the real-life aspect of that damage for your client – for example, when talking about loss of enjoyment of life, talk about how being depressed robs the plaintiff of feeling happy or content and how being on anti-depressants completely flattens his or her demeanor to the point of not feeling anything. And what is a life without feelings – good or bad? If your client used to be social and outgoing, talk about how that part of his or her life is now over and that all he wants to do is sit on the couch. Talk about how he really misses his or her friends but can’t find the courage to spend time with them. Then, for each category of non-economic damage, assign a past and future dollar value. Particularly if your client is young, convert your future non-economic request to a dollar-per-hour value.

Conclusion

There is no cookie-cutter way to proving injury and damages in any case, much less in an invisible-injury case. But, by really getting to know your client, participating in their care, shepherding the right experts, creating a panoply of visual aids, and always maintaining your integrity and credibility at trial, you can maximize your chance of getting true justice for your client.

Olivier Taillieu

Olivier Taillieu is the Managing Trial Attorney at The Dominguez Firm. He graduated from the George Washington University Law School in 1999 and went on to clerk on the Central District of California first and on the Ninth Circuit immediately thereafter. He now dedicates himself to representing people against insurance companies, corporations, and governmental entities. He has tried cases in both state and federal courts – in California and in other states.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine