The craziest client I ever represented

We’ve all had one

While serving as a Deputy Federal Defender in Los Angeles in the late 1970s, it was by luck of the draw that I came to represent the defendant on a retrial in United States v. Thomas W. Sullivan after a colleague had left the office.

Sullivan had been convicted of violating federal law by submitting false information regarding his prior commitment to a mental institution when he acquired firearms. In his own mind, the defendant was a high-ranking military officer entitled to own guns regardless of laws barring past mental institution patients from possessing firearms.

In Sullivan’s first trial, psychiatric testimony had been offered in his defense arguing that, by virtue of his mental illness, he lacked the capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or conform it to legal requirements. Sullivan had been quickly convicted. The Ninth Circuit reversed, based on an incorrect jury instruction regarding the defendant’s state of mind. (See United States v. Sullivan, 544 F.2d 1052 (9th Cir. 1976).)

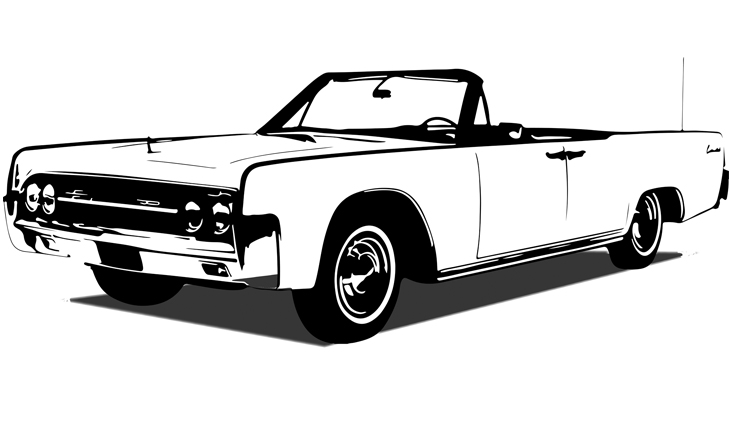

Sullivan had been arrested while driving around Los Angeles in his beat-up 1963 Lincoln Continental convertible with a trunk full of rifles, pistols and ammunition. He loved his firearms and felt fully justified in possessing them, prior mental commitment notwithstanding.

I scheduled my first meeting with the defendant a couple of months before the retrial in the office of the Federal Public Defender in the old federal courthouse at 312 North Spring Street, Los Angeles. On the appointed morning, I was advised that he had arrived. As I walked to the front of the office to greet my new client, I passed by the photocopy room and heard the machine whirring away, which seemed unusual for an early morning hour. When I got to the reception, I looked around and found no client.

To my surprise, the receptionist told me that Sullivan had been there for over half an hour but had gone directly to his “usual place” at the office copy machine. She said that he came in whenever it suited him and she had given up trying to deter him from making a beeline to the copy room. That’s where I headed.

I found Sullivan, a wiry little man wearing an overcoat and Panama hat, hunched over the copier. Stacks of paper covered the floor. When I tried to introduce myself and coax him away to discuss his case, he bellowed, “Go away. Don’t bother me. I’ve got important business to do. General Lansdale is waiting for my report in Washington.”

I had heard of General Edward Lansdale, associated with clandestine and psychological warfare in World War II, Vietnam and Cuba. But I had no idea what Sullivan was doing or what his huge copying project had to do with his defense. Before I could engage him, he yelled, “Go away and leave me alone!”

I backed off and returned a little later. Sullivan and his documents had vanished. I attempted to telephone him, but without avail. I sent several letters reminding him of the trial date and begging him to come in to go over his case with me. Other than reviewing the previous trial record, I was uncertain how to prepare for trial if he would not show up and cooperate. I asked our in-house investigator to find the defendant and get him to come in to speak with me. Sullivan never showed up to speak with me.

The trial day of reckoning before Judge Robert Kelleher finally arrived. I had tried cases before this judge before and liked his manner. He was straight out of judicial central casting: dignified, courteous, patient and careful. In the days when many federal judges hired an extra law clerk to act as the bailiff, he still retained a portly Irishman with a sharp eye to maintain order in his court. And order he maintained well.

Bracing for jury selection, I arrived at the courtroom for trial at 9:00 a.m. with my fingers crossed that the defendant would arrive on time. 9:15 a.m. – I am getting nervous. 9:30 a.m. – Searching for my investigator. Nada. 9:45 a.m. – With apparent satisfaction, the bailiff mentions the possibility of the judge issuing a bench warrant.

Finally, at almost 10:00 a.m., there is a loud commotion and a smashing of the outer door at the back of the courtroom. The door bangs open and in crashes Sullivan, frantically pushing a six-foot railed flatbed cart stacked with suitcases. He ignores a briefcase that tumbles off the pile as he pushes forward with all his might. He trips on the carpet while trying to retrieve it and loudly exclaims, “I’ve got the evidence. Here it is!”

The bailiff bolts out of his chair and rushes toward the maelstrom, shouting, “You can’t do that in my courtroom!” My investigator is trailing behind Sullivan as the cart careens into each row of the courtroom benches, banging one after another.

My poor investigator blurts out that Sullivan had pulled his battered convertible into the judges’ parking lot downstairs in the basement of the federal courthouse. He refused to budge and commandeered a loading docket cart to haul in his “evidence” for trial. The investigator exclaims with flustered frustration, “He’s a maniac. No one could stop him, not even security. They know him and only let him through because he said that he had a trial. It’s incredible.”

The cart smashes the little swinging door of the bar. Sullivan maneuvers it up to the defendant’s counsel table and begins dumping his cargo underneath. He pulls off his Panama hat and demands to know, “You don’t have a decent place for a man to hang his coat here, do you?” He then slides out of his overcoat and thrusts it at the bailiff, whose arms instinctively shoot out in self-defense. With intense indignity, the bewildered bailiff grabs ahold of the disheveled heap as Sullivan orders him to, “Hang this up.” The outraged law enforcer glares back at him with an expression of contemptuous disbelief but complies by neatly hanging up the crumpled pile on a nearby coat rack.

Relieved of his outer garb, Sullivan is wearing an outdated double-breasted suit that looks as if he has slept in it for a month. At least that’s how it smelled if one got close to him.

The defendant plops himself down at the counsel table and announces that he is “ready for action.” Everyone else, including the startled prosecutor who has been huddling with her case agent across the courtroom, appears to be tired out by just watching this spectacle.

With a disdainful expression, the bailiff straightens up the courtroom and stomps into chambers. The judge soon takes the bench as if none of this has occurred. Jury selection is ready to get off the ground.

As jurors start to fill the box, Sullivan is squirming in his seat next to me and repeatedly leaning down to pull items from a suitcase from under the table. I do my best to play it cool and act like everything is completely normal. It is anything but business as usual, especially with Sullivan audibly mumbling to himself about “the real evidence.” The judge ignores the defendant’s fidgeting, fills the jury box and launches into voir dire.

Not five questions into the court’s examination of prospective jurors and Sullivan jumps up and shouts “There, the fat lady. The one in the middle. I don’t want her. Get rid of her!” The judge pauses for a brief moment, completely disregards the defendant and continues addressing the jurors. I’m not sure whether to call further attention to Sullivan by counseling him to pipe it down or just focus on the jury box. I take the latter approach. So much for client identification.

As if out of nowhere, a female juror seated in a back row of the audience raises her hand and asks the judge if it is all right to have her eight-year-old son stay with her in court because she does not have childcare. Sure enough, a small young man who initially could not be seen is sitting next to her. The judge’s barely audible response is the clearing of his throat.

It’s now already getting close to noon and we are almost wrapping up jury selection. The judge calls time out and adjourns for lunch. I purposefully wait with Sullivan and my investigator in the courtroom to allow the jurors enough time to get as far away as possible before inviting the two to have lunch with me two floors up at the snack bar. We delay a moment at the elevator bank, grab the next one going up and step in. To my total amazement, the female juror who raised her hand and her son are standing in the elevator next to us. As the door shuts, I cannot fathom where on earth they came from.

As soon as Sullivan notices her, he levels a loud insult at her from not more than four inches away from her right ear, “You’re not bringing that ugly little kid onto my jury.” If I could have, I would have jumped out on the third floor, where she exits. But it was too late. My dear client has already done the damage.

When we return to court, I advise the bailiff that I wish to speak with the judge in chambers to tell him about this incident. Before I can relate what happened, the keeper-of-the-peace reads my face and says with a sardonic smirk, “And now what?”

In chambers, I explain to the judge what happened on the elevator. He summons the juror, sans offspring, into chambers and pointblank asks her if anything happened on the elevator after we broke for lunch. She looks at the judge with puzzlement and astonishingly says, “Not that I noticed.” End of inquiry. Fortunately, she never got called into the jury box and was excused to return to the assembly room when the jury is sworn.

The prosecutor’s opening statement outlines her case with simplicity. I wait my turn and muddle through. It should be a slam dunk for the government. She has tried the case once before and ought to be ready to shore up any weaknesses, especially the faulty jury instruction. To obtain a conviction, all the prosecution needs to do is to offer a certified copy of Sullivan’s mental institution commitment, proof of his weapons possession and present a psychiatrist to testify that Sullivan knew what he was doing. The damning photos of the gun collection piled high in the trunk of the defendant’s Lincoln convertible look like he had a military arsenal ready for war. The scene is set. But before the first witness is called, the judge mercifully adjourns early for the day.

I meet with Sullivan to talk to him about arriving on time for the second day of trial. I also need to get him to court without the fear of him plowing into a car in the judges’ parking lot. I was especially concerned about my investigator’s report that Sullivan had left his grand turisimo Lincoln convertible, the long model used by politicians and where beauty queens sit up on the back seat to wave at parade crowds, sprawled across two judges’ parking spaces.

I was already worried about receiving an embarrassing call from the Chief Judge’s clerk summoning me to explain why I had encouraged my client to park in the judges’ sacrosanct parking lot. To solve the transportation issue, I come up with an old standby straight from the Los Angeles traffic playbook. I suggest to Sullivan that he could save gas and avoid hassles by taking a free ride to court from my investigator. He bites at the bait and we make plans.

Miraculously, Sullivan arrives on time with my investigator for the next trial day. As the government’s case agent begins testifying, the back door of the courtroom opens and in saunters a well-recognized court watcher, none other than General Hershey Bar. Who? It is General Hershey Bar, the gadfly court watcher who parodies the Vietnam-era Selective Service Director General Lewis Hershey.

General Hershey Bar is well known for plying the halls of the federal courthouse in full mock Army uniform with a model airplane mounted on his saucer cap headgear, smaller ones for epaulets and colorful medals awarded for his good service to humanity. During the Vietnam War and even after, he has generously handed out “draft deferments” to anyone who might need one. That was too late for me since I had already served my military duty. The General’s presence adds an extra touch of ironic justice to a serious farce.

As the government’s psychiatrist is going through the paces of his testimony, I hear a couple of tiny effervescent explosions at my feet coming from under the counsel table. The alert bailiff must have heard the same thing. He perks up like a beagle and starts sniffing about. I venture a fleeting glance toward my client sitting next to me. He is bent over, doing something under the table.

It takes me but an instant to see that Sullivan has opened a couple Coke cans and is trying to take a hasty sip from one. I nudge him slightly. He jerks upright and spills both cans all over his pants, shoes and the carpeted floor. The bailiff has been monitoring his every movement. The observant serjeant-at-arms breathes out a long hiss as his face turns as red as a circus clown’s scarlet false nose. He readies to pounce but holds back.

The prosecution wraps up its case with evidence of Sullivan’s mental hospital commitment and now it would be my turn to present an affirmative defense. During our little lunch meeting the day before, I had asked Sullivan if he wanted to testify. I could have hardly asked him a worse question. He resentfully replied, “Testify? Are you kidding? What I know is highly classified. It’s between General Lansdale and me and no one else. Classified means classified. Got it?” Well, that surely decided that issue. His indignation relieves me from having to venture into unknown territory by calling him to the stand.

The psychiatrist that I put on is not very persuasive. The prosecutor has him tied in contradictory knots. Anyway, even I must ask myself, “What rational juror would want this nut riding around town with a cache of deadly weapons in his car trunk?”

The legal point on the instruction of law that had caused the first guilty verdict to have been reversed is fixed. It does not take long for the jury to return a new guilty verdict. The bailiff beams on the verge of delight as he assists in remanding the defendant into custody. After sentencing a month later, I never saw Sullivan again. Of course, an appeal was taken. It may have taken less time for the higher court to dispose of the appeal of this second conviction than for the bailiff to clean up the sticky mess left by the Cokes spilled on the courtroom carpet. (See United States v. Sullivan, 595 F.2d 7 (9th Cir. 1979).)

I never found out what happened to Sullivan’s old Lincoln Continental convertible or his classified mission with General Lansdale.

Michael L. Stern

Judge Michael L. Stern has presided over civil trial courts since his appointment to the Los Angeles Superior Court in 2001. He is a frequent speaker on trial practice matters. As an attorney, he tried cases throughout the United States. He is a graduate of Stanford University and Harvard Law School.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine