Taking a premises-liability case to trial in Orange County

Verdict on slip and fall at gasoline pump demonstrates that jurors respond to common sense safety protocols

A couple of years ago I received a call from my old friend Gilbert Perez, who works at Mauro Fiore’s office, asking me if I would try a premises case with him. I have known Gilbert for years and after he explained the case to me, I said yes without thinking much about it. I did ask to meet the client though. And there goes my first lesson about trying a premises-liability case: the client.

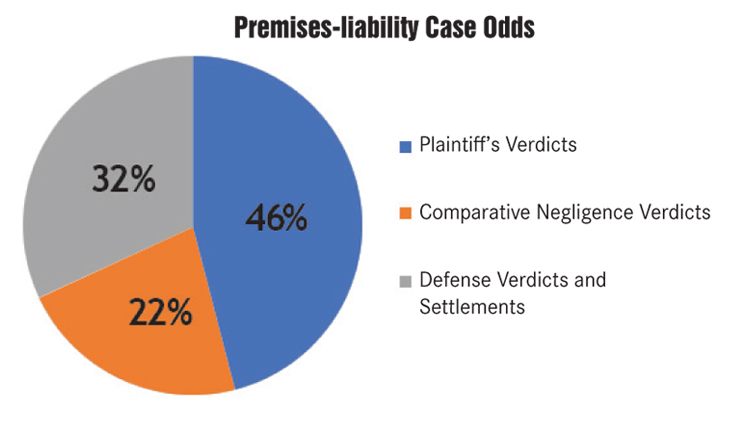

You see, premises-liability cases are probably some of the hardest cases to try. In the last five years, the only defense verdicts I have been subjected to were premises cases. I have yet to meet a juror who is excited to serve on a premises-liability jury. Here is a picture that speaks a thousand words:

So, the client matters. I would say that the client matters more than the facts. Luckily, I liked this client and I felt for him. He was a Turkish immigrant who had started a Mediterranean food truck business and slipped on a puddle of gas left by a prior customer at the gas pump. His injury was real – a torn quad tendon – but his damages were low. He had been able to get his trucks covered with his existing staff and it became clear to me this would be a non-economic damages case only. So, the client really mattered.

Here were the facts: Customer comes to fill his tank of gas and inadvertently spills some gas on the ground, as captured by a surveillance camera. (See Figures 2A-2B). Ten minutes later, my client gets out of his truck, walks around to the pump, and slips on the puddle. He tears his quadricep tendon and gets it fixed through his health insurance. Total medical bills: $8,000. He returned to work almost immediately after his surgery. So already we’ve identified four issues: Non-slippery concrete floor surface; no notice; fault of a third party; and all non-economic damages request. I certainly had my work cut out for jury selection. To top it off, the case was venued in Orange County.

I limited my voir dire to the main issues involved and kept it short. I got a few lucky breaks on cause but felt like I had a decent jury (for Orange County). And so, off to the races we went.

The main issue I needed to get around was notice. The case had been well prepared in discovery, but the focus was on the slipperiness of the floor, which I felt would not be convincing. Instead, I reframed the case to avoid the issue of notice altogether.

One of the first things that struck me was that a gas pump is not supposed to spill gas unless it’s securely fitted in a gas tank. I even tried an experiment at the gas station that night, and actually recorded myself trying to pump gas outside of my car.

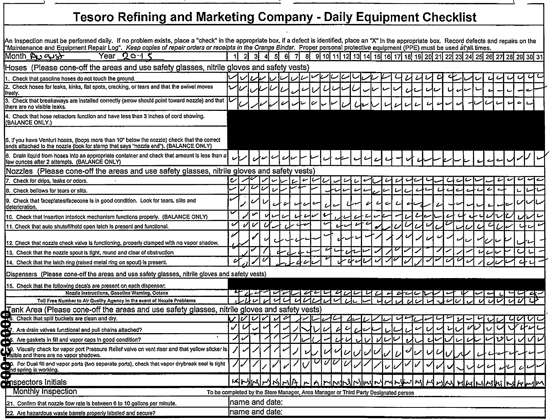

So the theme became one of direct negligence of the owners of the gas station by even allowing such a spill to happen. Luckily, we had the maintenance and inspection records for the pumps. Unluckily, they were perfectly filled out. Maybe too perfectly . . . (See Figure 3)

Little things matter and those details can break a case for you. Here, I noticed that the same person filled out the inspection sheet every day. Surely this person took a day off here and there, but all the inspection sheets had her name for every single day.

Moreover, I noticed that the inspection sheets had very specific requirements as to what to do and how. Wear a vest, gloves, bucket, etc. The sheets also specified individual components that needed to be checked. Like a “bellow” or a “face cone.”

The one skill that we all have is our common sense. If something doesn’t make sense to you, question it. Dig a little deeper. Our job as a personal injury lawyer is to question things and to almost be more of an investigator than a lawyer. And it’s never too late. You can change your mind, your theory, your themes at any time. This reframing in this case allowed us to see the case from a new, totally different perspective and ultimately carried the day.

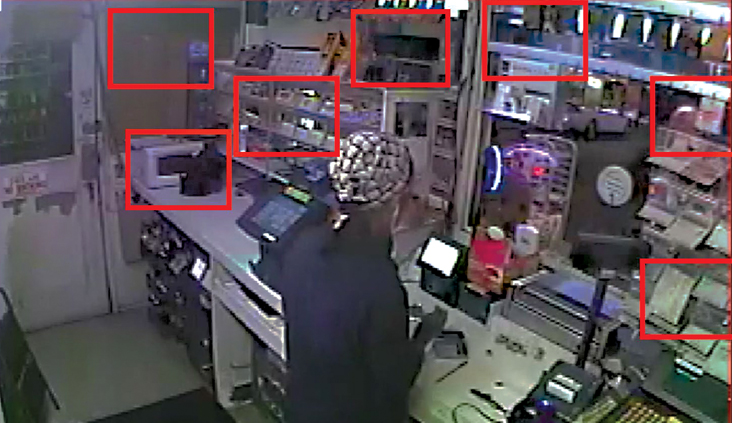

We also attacked on another front – one which would ultimately bite the defense in the shorts. Gilbert had made a request for video surveillance and had only received the part where the other customer spilled the gas and the part where our client slipped – which is typical in a premises case. I was committed to using that dearth of evidence against the defense somehow.

So, it went like this: I put the manager on the stand and I began asking about her work schedule. As expected, she told me she worked a five-day-a-week schedule. Then I asked her if she actually performed all the required inspections daily – to which she said yes. I reiterated the questions: “So, every day you are there, you put on your vest, your gloves, you take your bucket, and you go around to every pump performing the list of inspections that are listed on this sheet of paper and you fill this out?” – to which she responded “yes.” The next question was a gamble, but it worked. I presented this exhibit (See Figure 4):

And I asked her: “can you point out to the jury which part of this gas pump is the bellow?” . . . .Thankfully, she couldn’t.

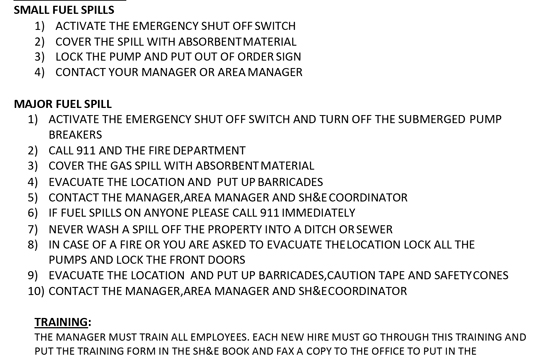

Next, although we decided to minimize the notice aspect of the case, we felt that we needed to address it. Is ten minutes reasonable? Probably, but notice is very fact specific. A ten-minute wait may be perfectly fine in a supermarket, but not for a gas station (we argued). After all, spills are the most dangerous occurrences at gas stations. We used some of their documentation to make that point (Figure 5):

But ultimately, we framed the notice issue as one of profit versus safety. As it turned out, the gas station owner had a full set of surveillance monitors installed (as posted on a sign warning of 24-hour video surveillance), but the monitors were installed in the manager’s office – which was locked and to which the clerk had no access. So, if there is a spill at one of the pumps the clerk has a very limited vantage point and cannot necessarily see it. A simple monitor near the cash register would solve the problem, but that is both expensive and would have to take the place of merchandise, as demonstrated by this exhibit in Figure 6.

In all of this, I had to be careful not to demonize the manager. Every trial needs an antagonist (“bad actor”) but you must pick that person carefully. I knew the jury would identify with the manager, maybe even feel sorry for her. I know I did. There was a woman, probably underpaid, working in a gas station for owners who were far more interested about profits than they were about safety. The shifts were long and the station understaffed. And none of the owners showed up at trial. They literally hung her out to dry. Needless to say, I made some hay out of that on closing: “How can an employee, working all alone, in a box, who is not allowed to leave even to take breaks, be expected to address a spill if they can’t see it?”

Also, in every premises case you must be able to answer the question, “What could the owner have done?” and the answer must be reasonable. Here, the monitors were an easy answer. Also, having proper maintenance and inspection routines would have prevented the problem. We had a good case of substantial factor. I also showed this safety cone to the jury (Figure 7):

Now onto the fun part. I don’t always tell the jury what I am going to ask for and I didn’t in this case. I wanted them to trust me before they heard a number from me. In this case, by the time we got to the damages, the jury saw the defense for what it was – lies. The inspection sheets were unreliable, the manager likely didn’t perform the inspections, she couldn’t name some of the most important parts of a gas nozzle, and the lack of monitors was inexcusable.

Life changes after the accident

I spoke to my client and his wife about the changes in his life on the stand. They were subtle, but they were there. I always try to find a connection that links the whole family together. I didn’t over-dramatize – just kept it short and sweet. In this case, the client had played semi-professional soccer as a young adult in Germany and I talked about his inability to share this passion with his son. His wife did a good job explaining how even though he doesn’t complain, he feels the pain daily and it has impacted his life. The injury contributed to him gaining 30-40 pounds, which we talked about how hard it was for him to lose.

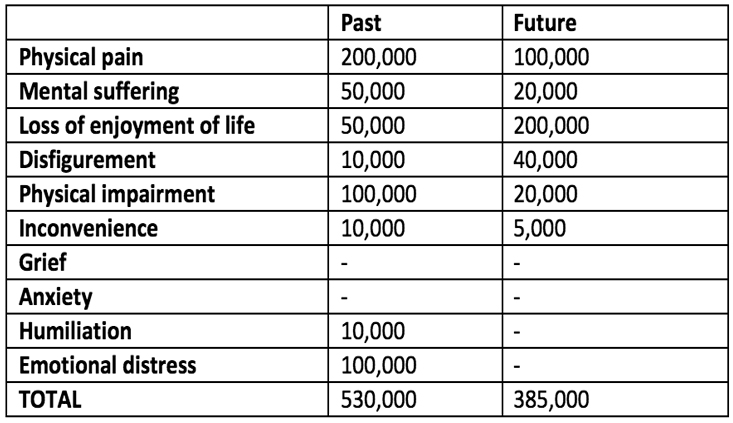

This was never going to be an eight-figure case, but I asked the jury to find for our client as follows (Figure 8):

I don’t always use this format but I felt that in this case, it worked. It ties the elements of non-economic damages to something real and tangible. I explained what each one of these categories meant and related it to the facts of the case.

On closing, I emphasized jury instruction 1005 which states that “[a]n owner of a business that is open to the public must use reasonable care to protect patrons from another person’s harmful conduct on its property if the owner can reasonably anticipate such conduct.” This was to deflect any liability on the third party.

I also used 230, which states that “[y]ou may consider the ability of each party to provide evidence. If a party provided weaker evidence when it could have provided stronger evidence, you may distrust the weaker evidence.”

Specifically, remember earlier when I said that I would make the defense pay for not disclosing much video footage? When all the evidence was in and I knew the defense couldn’t come and add some more, I asked the jury on closing: “If Ms. Manager really went out there every day, with her vest, and her gloves, and her bucket, checking every single pump, and the defendant has this 24-hour video surveillance system, don’t you think we would have seen it? OK, maybe not every day, but any day? In fact, you better believe that if she was actually going out there at any time it would have been the only thing we saw from the defense.”

Lack of evidence can sometimes be more powerful than the evidence itself. It certainly was in this case. In the end, the jury deliberated for a fairly short period of time and rendered a verdict giving my client everything we asked for to the penny. I have to admit that was a first.

Emboldened by this victory, I tried another premises case with Gilbert a year later, also in Orange County. I should I have quit while I was ahead . . . .

Olivier Taillieu

Olivier Taillieu is the Managing Trial Attorney at The Dominguez Firm. He graduated from the George Washington University Law School in 1999 and went on to clerk on the Central District of California first and on the Ninth Circuit immediately thereafter. He now dedicates himself to representing people against insurance companies, corporations, and governmental entities. He has tried cases in both state and federal courts – in California and in other states.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine