Arguing non-economic damages in a wrongful-death case

To achieve maximum non-economic damages, we must find and tell extraordinary stories

When a loved one dies, it is the non-economic damages that resonate with a jury. These damages for the loss to the plaintiff of the decedent’s love, companionship, comfort, care, assistance, protection, affection, society and moral support are the most economically substantial components of a wrongful- death case. In the overwhelming majority of cases, the value assigned these categories will be the largest portion of the verdict. Jurors faced with this unenviable task are given very bare-bones instructions, stating only: “No fixed standard exists for deciding the amount of noneconomic damages. You must use your judgment to decide a reasonable amount based on the evidence and your common sense.”

(CACI 3921).

Jurors are bewildered with how to approach determining these damages in deliberations. As our clients’ advocates, we need to give the jurors the raw materials – the evidence – they will need to understand what the plaintiffs had in their relationship with the decedent, and thus understand the magnitude of the loss. In final argument, rather than yelling or scoring points against the other side, you are providing the jurors with a reasoning process they can use with their fellow jurors to reach a just result based on the evidence.

Finding and crafting the story

To achieve maximum non-economic damages, we must tell extraordinary stories. Trial lawyers must spend the time and effort to creatively gather and present evidence of the plaintiff ’s loss in such a way that the jury can fully appreciate the magnitude of the relationship.

Every relationship is based on something that is unique and special. Our most important task as trial attorneys is to find ways to make the jury see and appreciate that unique and special something between the decedent and each heir at law, to entice them to fully compensate them for the losses they have and will suffer.

To identify the unique and special something about your clients’ decedent, you must first spend time with your clients. The primary purpose of these meetings is to learn the full story of their lives, the decedent’s life, and their relationships.

We prefer to meet them in their homes for a first-hand view of details about their lives and the stories that inform the relationship with their lost loved one. You can ask hours of questions about pictures and mementos you see on the walls, tables and shelves.

Meeting in a place where they are comfortable enables your clients to relax and feel free to discuss the intimate details of their lives. They can easily find and show you photographs, scrapbooks, letters, cards, notes, videos, and other memorabilia that bring their stories to life. Every one of these is a potential trial exhibit that convinces a jury this was an extraordinary relationship and an extraordinary loss. Each one is a potential prompt for testimony that highlights something unique and special about the decedent. Leave no stone unturned here. You never know what you’re missing unless you look.

Once you have the story of the decedent’s relationship with each heir from their own perspective, you widen the fulcrum of your search. Others like friends, extended family, spiritual advisors, teachers or mentors, and co-workers will add more blocks to the beautiful wall you are building as the story, including “pieces,” the heirs at law may not even know.

Other witnesses add credibility, depth, and breadth to the story, and show how the loss of the decedent did not just affect the plaintiffs, but an entire community. They also fortify the story you are telling against cynics and naysayers sympathetic to defense insinuations that the plaintiffs, who stand to gain money and may be recalling the past with rainbow-colored glasses, are credible and trustworthy.

For each person you talk to and meet with, make sure to explain the nature of the damages claim and its focus for trial. Ask direct questions about each of the elements that apply to the facts. If a witness agrees the decedent was very caring, for instance, that witness will have a story or an example that shows this quality in action, often one that can be tied to the pictures, video, letters, messages, or other evidence. They may have difficulty articulating, but stay with it, and it will bear fruit. Once you go through this process, the full scope of the loss and the extraordinary story within every decedent’s life and relationships will organically emerge.

Those qualities also must be placed in the narrative arc of the decedent and heirs’ lives. Every juror comes to this process as the hero of their own story, but they are ready and willing to see the decedent as the hero of a different story, and through the trial and the jury’s verdict, see those stories intertwine and impact a family and community.

Stories and the senses – a trial example

While telling the decedent’s story, think about the five senses to get your clients and witnesses talking and remembering important details that can bring his or her story to life.

What did people around the decedent see? What did they hear? What smells were associated with them? What was their touch like, and how did it make people feel? What foods or meals were significant, and how did they taste? These questions should be asked of every witness who can speak to the relationship. Profound insights and vivid descriptions often come from unexpected places, but especially when people break bread; share food and drink.

Below are some examples of the types of testimony elicited at trial in Rennie v. Fed Ex Ground Package System, a wrongful-death case of a mother who lost her 22-year-old daughter:

“When I saw Chelsea on her bike, I knew everything was right in the world. It put a smile on my face whenever I saw her.”

“I looked over at her grandfather, and tears were streaming down his face. He was so proud of her.”

“All I could see was this massive curly red hair. I could always pick her out in the crowd.”

“All I could hear was her killer clarinet solo. She stood there with one spotlight on her. You could hear a pin drop and then she started to play. So beautiful and moving. She held the last note so long. It was an electrifying moment. It was just so beautiful. This has to be one of my absolute favorite moments.”

“There was always music at the house. Of all different kinds. And now it is just silent.” “Hearing her music brought the community together.”

“Often I’d hear her praying and hear the little murmurings in there, and I knew she was talking to God, and I thought that she was so comforting to me. That was wonderful.”

“I could always feel her leaning into me when we sat next to each other.”

Testimony like this leaves strong impressions with jurors and creates powerful images that counsel can and must use in final argument to bring the story to life and to allow the life of the decedent and their relationships to feel as real as jurors’ own lives.

Using your raw materials

The information you gather in this process are the raw materials for telling the story at trial, but they work best when tied together by a strong theme. Distill your story down to one sentence: What would it be?

Think of a Hollywood producer or writer trying to pitch a story to the studio by articulating its theme in a clever, memorable way. Themes have always been used to motivate and stir people into action. When telling the story of your clients’ lives, you must do the same thing for a jury with the theme of the case. It is the one phrase that most embodies what the case is about. It is the first, the central, and the overriding element of any case story.

Gerry Spence refers to the theme of the trial as “a descriptive phrase or metaphor that symbolizes the soul of the case – a refrain perhaps.” The story should provide enough details to bring the story to life – but it should not contain too many unnecessary details that confuse the storyline.

As you craft your story, consider the graphics, slides, photographs, videos, or other exhibits that will enhance the story, but not confuse. The technology that we now have in our courtrooms makes storytelling easier and more effective. Today’s jurors typically expect and require this multimedia way of telling the story to hold their attention. The audio and visual component of your story and how you choose to highlight and emphasize witness testimony is crucial to the jury having a consistent picture of an extraordinary loss emerge as a case proceeds through trial.

Voir dire and jury selection

Preparing the jurors for final argument on the issue of non-economic damages in a wrongful-death case begins in voir dire. In addition to ferreting out closed-minded and hostile jurors for setting up cause challenges, jurors need education on their role in determining non-economic damages. Some prospective jurors simply believe they cannot place a dollar value on human life. Others have strong beliefs about caps on damages or against multimillion-dollar awards. Those must be identified and excluded. However, even open-minded jurors are often confused and uncertain about these concepts, and the panel as a whole should be questioned on their ability to follow the jury instructions, beginning with information that their job is not to place a value on life. It is to find a value for the loss of relationships.

Jurors should be questioned on their ability to award damages for each element set forth in the jury instruction. Jurors who indicate anything less than entire impartiality on any of the damages elements, or on issuing a large award for such damages if the evidence warrants it, is open to a challenge for cause. More open-minded jurors can be reminded that the combined life experience of the jurors and the evidence is their resource to draw from in determining an award, and asked to commit to being entirely impartial on the issue until hearing the evidence. With strong evidence in support of an engaging story, and a persuasive final argument, even initially skeptical jurors can and will return just non-economic damage awards.

Final argument

A case is won through meticulous preparation in every stage of the proceeding, from discovery and motion practice, to voir dire, through the examination of witnesses and presentation of evidence. However, an attorney’s final argument directly influences whether a plaintiff is adequately compensated.

Often, movies and television leave jurors with the impression that a final argument is a time for impassioned speeches, shouting, or counsel engaged in witty sparring about the finer points of the case. Attorneys, fixated in final argument on the facts of the incident itself and on minutiae relating to disputes about the evidence and witness credibility, often play to this preconception. Instead, counsel should explain early on in your presentation that final argument is an invitation for you and the jury to reason together. That the attorney is laying out a reasoned process and a rationale the jurors can take with them into the jury room and use while deliberating to determine the amount of a reasonable award. This is incredibly important because the jury has just heard extensive instructions from the court on liability, causation, damages, but did not and will not hear extensive instruction on how much compensation to award and how to think about that decision unless the attorney provides it.

Wrongful-death cases elicit a tremendous amount of inherent sympathy, compassion, and anguish. However, an attorney must evoke more than those things with their final argument. The jury must have solid reasons to return a plaintiff verdict and why justice must be done, even when there is no economic loss to be decided.

Our approach in final argument is firmly grounded in the elements of damages provided in the jury instructions. These non-economic damages elements are loss of love, companionship, comfort, care, assistance, protection, affection, society and moral support. The jury should be reminded from the instructions what the elements are, including definitions and synonyms for those terms. For example, for the element of loss of love, we present the following on a slide and explain it to the jury:

love: a profoundly tender passionate affection for another. A feeling of warm personal attachment or deep affection for a parent, child, spouse, or friend. Synonyms: tenderness, fondness, warmth, passion, adoration, devotion.

As jurors’ understandings of each element is broadened, like love, they begin to consider more pieces of the evidence they learned during trial that fits within all of the elements and each must be compensated. A skilled attorney does not leave this to chance. Final argument should include presentation of applicable direct quotes with citations from the trial testimony, photos and videos in evidence, and preferably a combination of testimony and visual aids, that supports each element and all relationships between the decedent and the heirs at law. This gives the presentation credibility and a quality of certainty. Rather than feelings or sympathy, the jurors are educated that substantial evidence supports a large award for each element.

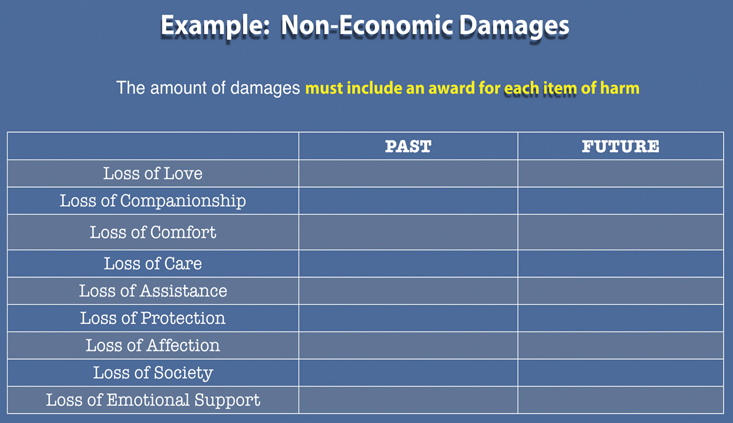

Importantly, the instruction to the jurors that, “the amount of damages must include an award for each item of harm that was caused by the defendant’s wrongful conduct,” must be strongly emphasized. Defense counsel often try to distill the non-economic damages award down into a single number for the past losses and a single number for the future losses. A properly educated jury on the meaning of the instructions will understand that their verdict must include an award for loss of love, an award for loss of companionship, and so on, through each element.

The best way to do this is with a chart (See page 18) that can be shown directly to the jurors. This lets the jurors take clear notes of the amounts you propose, and encourages the jurors’ creation of their own similar chart in the jury room as they deliberate. When presenting this chart, you should give suggested award amounts for each element in the past and future. This chart and award amounts should not be addressed in final argument until after the evidence supporting the relationship gathered from the testimony and exhibits is presented.

As you go through your chart, summarize your reasoning for your award, and challenge the defense to do the same for their suggested awards.

Lawyers are uncomfortable asking jurors for large sums of money for non-economic damages. Why is that? And how do lawyers get comfortable? With a well-prepared case and a focused presentation of the evidence, both the attorney and the jurors are prepared to believe with good reasons and conviction that the large amount sought is justified and fair, even if it sounds like a lot of money. When arguing damages, the attorney must feel entirely comfortable about the clients’ case and be willing to have the courage and devotion to ask for the amount that is fair and just for each and all heirs at law. If the jurors are not convinced that you believe with your whole heart and soul this amount is fair and just, they will never award it.

During the argument, it is important to explain to the jurors their role in their community and in history. Juries have been awarding money for non-economic losses for wrongful death throughout the history of the United States, and it is not unusual. However, it is important and significant, and jurors should be encouraged to feel the weight of their decision and be inspired to do their best. Collectively, the jury has an opportunity to be more than any one juror can be. Given the opportunity, the jury wants this case to be bigger than the parties to this one lawsuit. The jury wants to feel they have spent their time to benefit the community and make it a better place to live.

Your final argument needs to be both a compelling story of who the decedent was and what the plaintiffs, heirs at law, have lost while providing jurors with a framework to understand the reasons the award you suggest is appropriate and to assist the jurors to advocate for your clients during deliberations. Hopefully, some of these tools will enable you to communicate with your jury about the losses your clients have suffered and enable them to achieve the fair and just result they deserve in a wrongful-death case.

Brian Panish

Brian Panish is a partner at Panish, Shea & Boyle LLP in Los Angeles. He is a member of the Inner Circle of Advocates. He specializes in litigating catastrophic injury or wrongful death cases on behalf of plaintiffs. (www.psblaw.com)

Patrick Gunning

Patrick Gunning is an associate at Panish Shea & Boyle, LLP in Los Angeles, California. A graduate of UCLA School of Law, Mr. Gunning is licensed in California and has practiced for five years exclusively representing plaintiffs in personal injury, wrongful death, and products liability cases.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine