Keeping the “material” in material facts

Understanding how to dispute, and draft, material facts is a critical tool in your summary judgment arsenal

If you struggle with writing material facts for summary-judgment purposes, you are not alone. A “material fact” is difficult to define. But understanding what makes a fact material will help you not only in drafting your material facts in opposition (or bringing your own motion for summary adjudication, you go-getter!), but also in disputing the defendant’s allegedly undisputed material facts.

This article is a companion to “Mastering the separate statement,” published in the December 2018 issue of the Advocate. Some examples may repeat, but are included here for consistency and so you can see them from a different perspective.

What is a material fact?

While the Code of Civil Procedure requires that a material fact be set forth “plainly and concisely” (Civ. Proc. Code, § 437c, subd. (b)(1)), the Code does not define what a material fact actually is. The California Rules of Court defines “material facts” as “facts that relate to the cause of action, claim for damages, issue of duty, or affirmative defense that is the subject of the motion and that could make a difference in the disposition of the motion.” (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1350(a)(2).)

The Court of Appeal provided a more substantive definition in Riverside County Cmty. Facilities Dist. v. Bainbridge 17 (1999) 77 Cal.App.4th 644, 653, explaining, “To be ‘material’ for purposes of a summary judgment proceeding, a fact must relate to some claim or defense in issue under the pleadings, and it must also be essential to the judgment in some way.” (Emphasis added.)

Let’s break this down. A material fact is:

A plain and concise statement of fact

Relevant to the claims or defenses in issue under the pleadings, and

Presented in the motion for summary judgment/adjudication that

In some way influences the court’s decision on whether to grant or deny the motion.

But even that definition of a material fact is not particularly elucidating. The definition of a material fact takes a more concrete shape when conceptualized in two other ways: (1) in the broader scope of the search for truth and justice; and (2) by what a material fact is not.

In search of truth and justice

The law cherishes truth in the pursuit of justice. Think about these principles in the context of the summary judgment statute. A motion for summary judgment asks the court to find that presenting your client’s case to a jury would be a waste of time, because under these undisputed facts, the plaintiff has no claim as a matter of law. The court must decide whether there is a triable issue of material fact – a material dispute for the jury to resolve in order to determine the truth and administer justice.

Research matters

How does the court decide if there is a disputed question of material fact to send to the jury? By applying the facts of the case to the applicable law. Thus, knowing what makes a fact material requires a thorough understanding of the law as it applies to your case. Knowing the elements of a cause of action is not enough. You have to understand: (1) the facts of the cases you will rely on; (2) the facts of the cases the defense relies on; and (3) how you will distinguish the defendant’s authority or otherwise argue it is inapplicable. Only then can you understand what makes a fact in your case “material.”

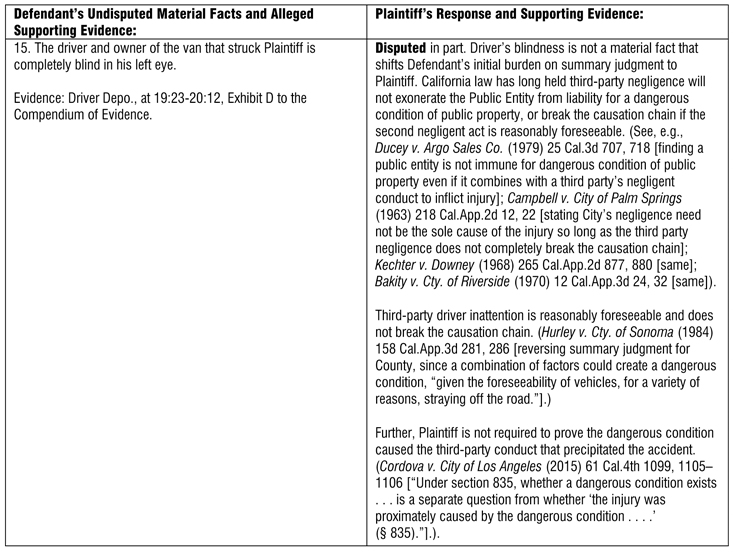

”But the driver was blind…”

Appreciating what makes a fact material to your case will not only help you draft your own material facts, but also will help you dispute any true but immaterial facts the defense sneaks into the moving papers. For example, a public entity defendant includes in its Separate Statement that the driver who struck your plaintiff was blind in one eye. While this “fact” is true, it is not “material” because it does not help the court find the truth – whether there is a triable issue on the public entity’s liability for a dangerous condition of its property. (See Figure 1.) When you know the case law, you can “Dispute” the allegedly material fact by showing the court why that fact is not material to the City’s claimed immunity.

Getting to truth

The search for truth is why, when identifying the supporting evidence, I include every piece of deposition testimony or documentary evidence I have supporting the material fact. Although on summary judgment the court must not weigh the evidence (Mann v. Cracchiolo (1985) 38 Cal.3d 18, 39) or make credibility determinations (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (e); AARTS Productions, Inc. v. Crocker Nat’l Bank (1986) 179 Cal.App.3d 1061, 1064), showing the court your material fact is the truth lends credence to your arguments.

Keep the principles of searching for truth and justice in mind to help you appreciate what makes a fact material.

A material fact is not evidence

Consider this supposed material fact: “Driver testified that she failed to brake and hit the plaintiff in the crosswalk.” As you’ve probably inferred, that is not a material fact. But why not?

Consider another example: “Harasser testified he never touched the plaintiff’s breasts on the job.” Again, not a material fact. Why? Because sometimes people lie. Sometimes people even lie under oath. Remember, the law is interested in truth. What someone testified to in deposition may be evidence of a truth, but the fact of the testimony is not a truth that helps the court in its search of justice. Because, sometimes, people lie. Even under oath.

The appropriate material fact – i.e., the truth the court is interested in – is, “Driver failed to brake and hit the plaintiff in the crosswalk.” Or, “Harasser never touched the plaintiff’s breasts on the job.”

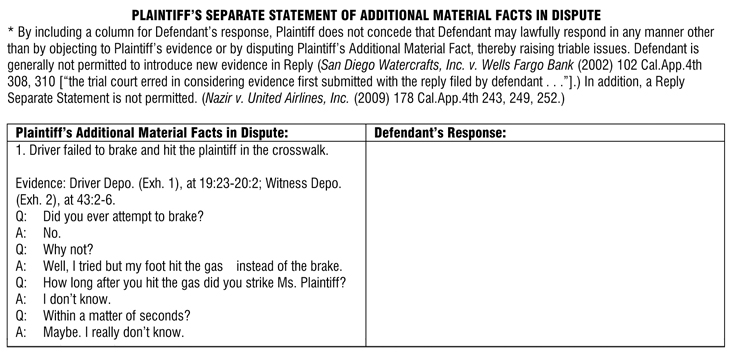

Framing a material fact in terms of its supporting evidence is tempting on both sides. From the defense perspective, presenting a material fact as the evidence makes it appear “Undisputed.” From the plaintiff’s perspective, we may want to emphasize an admission against interest, with its “high credibility value” (D’Amico v. Board of Medical Examiners (1974) 11 Cal.3d 1, 22). If you really must emphasize a particular piece of evidence for the court (and rarely, should you “really must”), quote the actual testimony with your supporting evidence in the Separate Statement. (See Figure 2 on page 55.) But do not frame your material fact in terms of its supporting evidence. Seldom will what a person testified to in deposition – the fact of the testimony – be a true material fact.

(Note re Figure 2: In Mastering the Separate Statement, I indicated that I do not include a column for Defendant’s response in the Plaintiff’s Separate Statement of Additional Material Facts in Dispute. The California Rules of Court is silent on the format for plaintiff’s additional material facts, and, as noted below, a Reply Separate Statement is improper. Neither the Code nor the California Rules of Court contain a mechanism for submitting a Reply Separate Statement. However, I have since changed my mind on formatting the plaintiff’s additional material facts. The defendant will almost certainly make objections to the supporting evidence, which should be identified by Objection No. in the adjacent column.)

Also, preemptively pointing out that disputing the plaintiff’s additional material facts often leads to an “Undisputed for purposes of this motion” response. Remember that Plaintiff’s Separate Statement of Additional Material Facts in Dispute allows the plaintiff to present the material facts the defendant omitted or skewed – the ones you need to argue based on your research of the law as it applies to your case. The trick to drafting the additional material facts is to make the defendant’s response irrelevant. If the defendant “Disputes” the additional material fact, the defendant creates a triable issue for the jury. If the defendant responds “Undisputed for purposes of this motion,” the defendant has conceded that the material fact is both a truth and material. Now you can show the court why, under the case law you spent so much time researching, there are issues of material fact that the jury must decide in order to determine the truth and administer justice.

Now consider this material fact: “Witnesses A, B, and C all saw the plaintiff crossing in the crosswalk.” This one is a true material fact, right? Because we’re not stating that Witnesses A, B, and C testified they saw the plaintiff in the crosswalk?

Nope, sorry; not a material fact. The plain and concise truth the court is interested in is, “The plaintiff was crossing in the crosswalk.” Eye-witnesses can be mistaken about what they saw, or heard, or perceived. Memories can be faulty. What someone honestly believes she saw may not be the truth. Seldom will what someone perceived (or testified to in deposition) be a truth that is in issue and in some way essential to the court’s decision on summary judgment.

In Reeves v. Safeway Stores, Inc. (2004) 121 Cal.App.4th 95, 105-106, the court lambasted the defendant for attempting to avoid “Disputed” material facts by framing them in terms of what a witness testified to or perceived. The defendant’s Separate Statement was so egregious that the appellate court authorized trial courts to strike alleged “undisputed material facts” that fail to comply with the Code, even if striking non-compliant facts means the defendant cannot carry its initial burden on summary judgment. (Id., at p. 106.)

At the threshold we observe that defendant has made our task – and that of the trial court – considerably more burdensome by its failure to comply with the requirement of Code of Civil Procedure section 437c, subdivision (b)(1), that the moving party set forth “plainly and concisely all material facts which the moving party contends are undisputed.” [ ] Instead of stating clearly those material facts which actually are without substantial controversy, defendant offers a number of obliquely stated “facts” that are material only to the extent they are controverted, and uncontroverted only to the extent they are immaterial. For instance, defendant asserts various “undisputed facts” in terms not of relevant events but of what a witness has said about events, e.g., two Safeway employees “stated that Plaintiff followed them out of the store, telling them that he had moved Sandy Juarez out of the way by lightly/gently pushing her aside.” It seems indisputably true that Brian Sparks so testified in deposition, though there is no competent evidence of such a report by the other worker, Barbara Flagen-Spicher. [ ] But what Sparks (or for that matter Flagen-Spicher) might have said in deposition is not, as such, a “material fact.” It is of interest only as evidence of a material fact, e.g., that plaintiff made a damaging admission about his confrontation with Juarez. That “fact” is squarely controverted by plaintiff’s declaration that he made no such statement. We emphatically condemn Safeway’s attempt to circumvent that conflict by stating the supposed “fact” in an attributive form.

This stratagem takes an arguably even worse turn in Safeway’s assertion of “facts” in the form of supposed perceptions by witnesses. Thus it is said to be undisputed that “Brian Sparks overheard” something, and that “Sandy Juarez and Staci Siaris both witnessed” something. Ordinarily, however, the perceptions of witnesses are simply not “material facts,” as that term is used in the summary judgment statute. The relevant question is whether the underlying facts – the events or conditions witnesses say they perceived – are established without substantial controversy. Defendant merely clouds the inquiry into that question by formulating the operative facts in the intermediate form of a witness’s perceptions or statements.

We believe trial courts have the inherent power to strike proposed “undisputed facts” that fail to comply with the statutory requirements and that are formulated so as to impede rather than aid an orderly determination whether the case presents triable material issues of fact. If such an order leaves the required separate statement insufficient to support the motion, the court is justified in denying the motion on that basis. (See Sec. 437c, subd. (b)(1).) . . .

(Reeves, supra, 121 Cal.App.4th at pp. 105-106 [original italics].)

A material fact is not evidence. Do not frame a material fact in terms of the supporting evidence. “Expert opines that . . .” is not a material fact. Nor are a witness’s perceptions a material fact. Do not make the same mistakes excoriated in Reeves, supra, no matter how well-intentioned you may be.

You only need a single disputed material fact

A defendant moving for summary judgment bears two burdens: (1) the burden of production – presenting admissible evidence, through material facts, sufficient to satisfy a directed verdict standard (Aguilar v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (2001) 25 Cal.4th 826, 851); and (2) the burden of persuasion – the material facts presented must persuade the court that the plaintiff cannot establish one or more elements of a cause of action, or a complete defense vitiates the cause of action. (Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (p)(2); Aguilar, supra, 25 Cal.4th at p. 850.)

Defeating summary judgment requires only a single disputed material fact. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 437c, subd. (c) [a motion for summary judgment “shall be granted if all the papers submitted show that there is no triable issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law.”] [emphasis added].) Thus, any disputed material fact means the court must deny the motion – the court has no discretion to grant summary judgment. (Zavala v. Arce (1997) 58 Cal.App.4th 915, 925, fn. 8; Saldana v. Globe-Weis Systems Co. (1991) 233 Cal.App.3d 1505, 1511-1512.) Further, a defendant may not avoid the denial by withdrawing the material fact. When a party includes a material fact in its separate statement, the party concedes it is material. (Nazir v. United Airlines (2009)178 Cal.App.4th 243, 252.)

However, do not rely solely on a technical error – e.g., disputing a true but immaterial fact; asking the court to strike non-compliant material facts such as those in Reeves, supra; or objecting that the defendant failed to support the material fact with admissible evidence – to defeat summary judgment. Such a strategy is extremely risky; if the court disagrees with your interpretation of the law, your client has lost the opportunity to oppose the motion on the merits.

Alyssa Kim Schabloski

Alyssa Kim Schabloski is a trial attorney with Gladius Law, APC. A plaintiff’s lawyer for her entire legal career, she practices in employment law, medical malpractice, and catastrophic personal injury. Alyssa graduated from Barnard College and obtained her JD and MPH from the UCLA Schools of Law and Public Health. She served as 2020 President of the Los Angeles Trial Lawyers’ Charities (LATLC) and President of the Cowboy Lawyers Association from 2019-2021. She is a member of the CAALA Board of Governors. Alyssa is admitted to practice in California, Arizona, and New York.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine