The recipe for success

The missing ingredient so often is proper evaluation of the case for trial: should this case be tried?

It’s 5:30 a.m. on a random Tuesday. I have another hour before my alarm goes off. Then, out of the blue echoes that distinctive sound of an electronic bell chiming. I look over and it’s a text from a colleague:

“The defense had until midnight last night to accept my demand...blah, blah, blah. I’m going to trial in 2 weeks.

Me: Thanks for letting me know that at 5 in the morning. Good luck. Text me if you win.

Colleague: Dude, I couldn’t sleep last night. Can you please, please jump in on this case?

Me: Only if we can beat the defense’s last offer by enough to make it worth it.

Colleague: Can you determine that?

Me: Of course. How do you think I pick the cases I try? Send me a link to the file and I’ll call you in two days.”

From a simple text at sunrise, I stay awake staring at the ceiling wondering what the plaintiff is like, what happened to them, how bad the defendant’s conduct was, who the jurors are going to be and what I’m going to say to them this time. The reason? It’s never too early to begin evaluating what you’re going to say at trial even if you don’t know what the case is about yet. Sounds crazy, right? Well, it may be.

For a good part of the week, I’m on the phone giving advice to people on how to win their cases and over the years the message has been the same. Everyone, except those who have decided trying cases is not for them, is searching for that same holy grail of litigation: the big jury verdict.

Yet, it’s elusive for so many, causing even those who thought they were the best to question: How did I get defensed on these facts? Why was the verdict so low? Why was the comparative fault so high? They found liability with no causation? I knew they didn’t get “substantial factor!” I can’t believe I didn’t beat their 998! Should I pick a different career? (This last one haunts you for a while).

After years of asking myself these questions, while scratching my head and sometimes hitting it based on the amount of costs I just lost, I realized that the answers were all the same: I seriously misevaluated some outcome-determinative aspect of the case and either didn’t present it correctly or shouldn’t have presented it at all. The defense got it right and I got it wrong. There was an error in evaluation and judgment on my part. That’s it, there was no more mystery.

“But wait a minute,” I would retort, “how could you have been so sure about something you were so wrong about? You did everything right from filing the complaint through the close of discovery, and then tried a great case. What did you miss?”

The beauty of a trial

And therein lies the beauty of a trial. One side gets it dead wrong when they were so sure they were right that they begin questioning their existence. Meanwhile, the other side is popping champagne, posting their verdict, embellishing its difficulty, timed perfectly to coincide with the next bar association mixer where they show up with bells on! It’s a beautiful dynamic, right? Well, only if you’re the one popping the champagne.

But have you ever wondered why you hear the same names getting consistent results year in and year out, while others continue to pose existential questions with some wins peppered in between that keeps their hope alive?

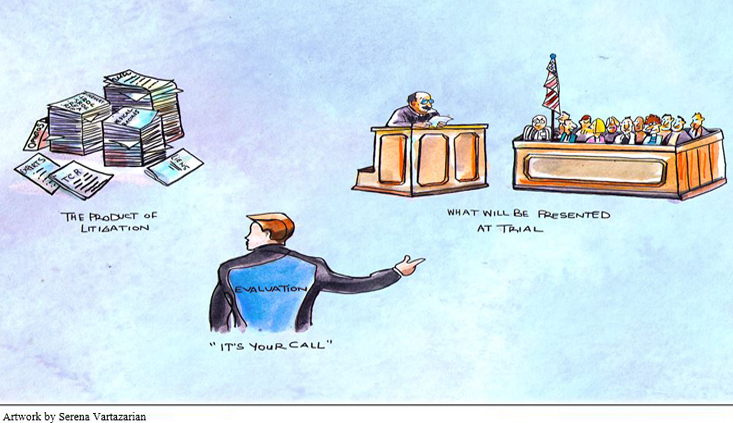

After years of pondering this, I began doing things differently in search of this skill set until I made a cathartic observation one day. I was spending half my office time in the conference room evaluating the next case I had set for trial. I would start by making a pile of things I knew the jury would believe and another pile of claims I knew were “iffy,” and then took it from there. I also observed that my time was spent doing one of three things, to which I assigned a percentage of importance based on how much influence I believed it had on the outcome of a trial. The product of this exercise resulted in the following:

1. Litigation: 35%

2. Trial: 15%

3. Looking at the product of the litigation from the last two years and thinking about what and how to present it at trial: 50%

I call this last category “evaluation” and refer to it interchangeably with the term “judgment.”

Let’s define these three things

Litigation concerns spending time perfecting the pleadings, carefully propounding and responding to discovery, taking and defending important depositions effectively, being proficient in law and motion, retaining the right experts, working up the damages, etc. The list goes on to include everything short of trial.

Trial concerns showing up prepared, getting things you need into evidence to carry your burden, and not making outcome-determinative (big!) mistakes. That’s it. It’s really that simple and anyone can do it. Don’t believe me? Consider that if I gave you a script from one of my trials from beginning to end, and all you had to do is repeat exactly what I said to the same jury, anyone would get the same result nine out of 10 times. So, what’s the trick? It’s coming up with what to say. Not so much the execution.

I then found myself spending most of my time thinking about what to say versus simply presenting what my experts had to say, which would leave the outcome of the trial in their hands. From these mechanics I realized that executing the actual trial itself was only 15% important to its outcome. While 50% of the outcome was influenced by correctly evaluating the evidence before trial to come up with only the right things to say once you got there. Although this is an extremely time-consuming process, I realized how important it was and spent years developing it into my most valuable skill set.

Then it hit me. The reason people refer cases to someone for trial is not because they can dazzle the jury, which is only a part of it. It’s because of their pre-trial evaluation skills and judgment of what to present at trial and how to present it. This is the skill responsible for their consistent wins. Trial is just where you can go see them having all the fun because they spent months setting it up correctly.

Let’s take a moment to debunk a myth

In the last 10 years an image has emerged that to hit a big verdict you have to be a charismatic storyteller dressed like a cowboy who gathers jurors around the proverbial campfire to tell them a suspenseful and sad story that ends with hope only they can provide through their verdict.

This may work for some, but it’s this belief that has caused numerous well-intentioned lawyers to spend thousands of dollars on cowboy boots and three-piece suits. The result: They still get the same disappointing verdicts except now they’re just wearing cowboy boots while doing it. The truth is, you can hit an eight-figure verdict wearing a $97 suit, shoes included! With the right evaluation and judgment, any one of us can hit consistent multi-million-dollar verdicts all year long — even a small-time lawyer tucked away in the Valley, camouflaged into a sea of litigators spanning the length of Ventura Blvd., all trying to break the surface at the same time.

That was me until I started doing this one thing differently. You can do a great job litigating the case and flawlessly executing the trial. But, if you present the wrong claims or fail to evaluate a piece of evidence correctly for trial, you’re going to get an untoward result that causes years of dedicated hard work and good money to go down the drain. That’s why the evaluation is so, so important and is the glue that ties the litigation to the verdict. This is the skill set that’s in demand.

Before I became conscious of how much time I was spending evaluating evidence before trial, I did notice a common theme emerge a month or two beforehand. I would spend a lot of time applying what appeared to be this abstract two-part evaluation that I can now describe as follows:

Evaluation: Part 1

Trial is only meant for certain cases. For starters, please understand that a successful trial lawyer can only make a good case, great. Even the best trial lawyer on the planet can’t make a bad case great, no matter how shiny their boots are or how well they tell a story. So, if your client was the one who rear-ended the defendant, please don’t call me.

Cases meant for trial can be described as follows:

1. Cases that have some value. Where liability and causation exist, and the damages are appreciable enough to warrant jurors taking time out of their lives to be there. It doesn’t have to be a tearjerker. It just has to be enough of a worthy cause that jurors can appreciate why they are there.

2. The defense has completely botched their evaluation of the case value. If your case value is a solid $10, and the defense is offering you $6-$8, the case is going to settle. It’s when the defense offers you $2-$4 that the case should be tried. Look at it this way, it’s as much of a disservice to our clients to accept $3 on a case worth $10, as it would be to try the case when the offer is $8. This is where principle and courage factor in, which are indispensable ingredients if you’re even thinking about trying cases. It’s that $5 difference that makes it all worth pursuing. If my case meets these two elements in this first part of my evaluation, I move on to Part 2. All other cases are settled.

Evaluation: Part 2

If mishandled, even the best case will be brought in for much less than its actual value. When you have a great case, defense attorneys are just waiting to capitalize on mistakes we make, which is all they have sometimes. This is why you see successful trial lawyers mostly handling big cases that some consider “no brainers.” I have several memories of people whispering in my ear, “no wonder they got that verdict, they had a quad with great liability and the defense was denying everything. Between you and I, I could’ve gotten the same result.” Yeah...maybe.

But one must consider that successful trial lawyers consistently get these results because they have a track record of not making mistakes in judgment, more so than their performance in front of a jury. And what I mean is, they don’t make mistakes in deciding what’s going to be presented at trial. Months before, they’ve evaluated everything correctly and their judgment on what to present and how to present it is spot on. That’s all there is to it. That’s the skill. This is the reason people refer cases to them.

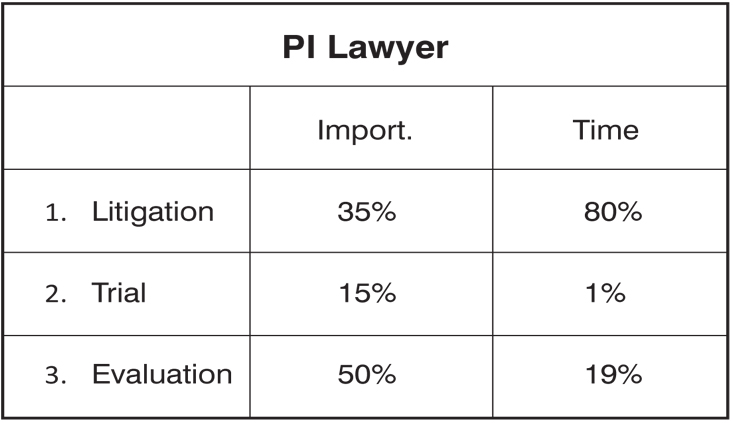

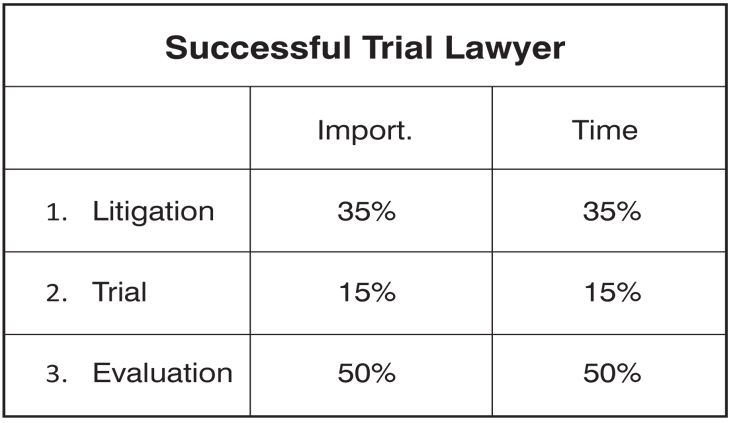

To demonstrate this point based on my observations, I’ve assigned percentages to how important (“Import”) each of the three categories is to the outcome of a trial. But now, I’ve added the amount of time two different groups of lawyers spend in each category. These two categories consist of those who want to be successful but don’t know what they’re doing wrong versus those who have proven their success in trial year in and year out.

As you can see, an average PI lawyer spends most of their time in the litigation process, from filing the complaint through concluding expert discovery, counting on the case to settle somewhere along the line. They’re preoccupied with lots of depositions, lengthy written discovery, unsuccessful initial mediations, etc. In contrast, successful trial lawyers prioritize their time differently. They spend no more time than it takes to get what’s needed to meet their burden at trial, and don’t waste time doing things that aren’t likely to bear fruit.

Also, the average PI lawyer spends a very small part of their time in trial versus the successful trial lawyer who spends an average of two months out of the year there, which makes them much more proficient. But the most important distinction emerges in this last category that I’ve dubbed “Evaluation.”

Successful trial lawyers spend half their time looking at the product of the litigation and molding it in a way that garners them credibility at trial, which they can then translate into a win. To the contrary, many PI lawyers evaluating what to present at trial default to the strategy of, “well, let’s just throw it all up and see what sticks. Hell, we’ve already paid the experts to testify.” Or even worse, “well, we have way too much in costs to settle the case now. If they would’ve offered that three months ago, we would’ve taken it. But now we just gotta go for it and roll the dice.”

This is the basis for my observation that average PI lawyers appear to spend 19% of their time in Evaluation when they should be spending 50% of their time in this category coming up with a more sound and reasoned strategy. The 31% discrepancy in this category, that amounts to coming up with only the right things to say, is what separates the consistent cream of the crop from those questioning where they went wrong while driving away from a bad verdict.

It’s this difference in time and effort spent that causes one group of people to ask all the questions posed in the beginning of this article, while the other group posts up with a cocktail at the next mixer waiting to run into their colleagues. This is what it comes down to: Only present credible evidence at trial and throw everything else in the trash – no matter how tempting it is to present or how much it cost. Once I switched to this approach, I immediately started getting better and consistent results, and here’s how I went about doing it.

First, let’s talk about what not to do

Let’s take a moment to discuss how pre-trial evaluation can be royally botched. There are particular vulnerable areas where plaintiff’s attorneys are susceptible to making evaluation/judgment errors. In today’s age of doing life-care plans for whiplash injuries, doctors so willing to perform surgeries on liens and testify to questionable causation, and other experts quick to find marginal liability, there are numerous traps set just waiting to ensnare the unwary.

On a regular basis, files are sent to my office that consist of zero-liability cases, bogus claims of brain injury, unsubstantiated future surgery recommendations, baseless wage-loss claims, denials that the plaintiff has any comparative fault when they clearly do, inflated medical bills, unnecessary lien treatment, exaggerated life-care plans, etc. The list goes on and on.

I used to get upset when I saw this, but then I realized it’s not their fault because this is what most of us have been taught to do. At some point in our careers, we were given a template used by our predecessors on how to “work up” a case. I then realized that all these templates created by our predecessors encapsulated the same basic premise: You don’t just take the case the way it comes and let it develop its value organically. You have to give your case value by “working it up,” which means doing most or all of the things I just described. In other words, genetically modify it.

If you don’t believe this is what we were taught to do, just walk into any legal exhibition hall where you can find a never-ending smorgasbord of outfits just waiting to help you “work up” your case. Look at all the tote bags, stress balls, calculators, back scratchers, pens and post-its in your office with numbers to call as soon as you get that case. I’m not saying these folks don’t have their place. They certainly do and I use them appropriately, but not every plaintiff needs an injection, a life-care plan, and to get worked up for a brain injury, if you catch my drift.

The 1980’s are over

We must recognize that the 1980s – and how cases were worked up then – are over. Jurors are savvy now and don’t buy half the crap we’re peddling these days that our predecessors got away with long ago. Due to tort reform propaganda, and the overall image of the ambulance chaser running after that payday, jurors show up as skeptical and untrusting as ever even as they sit in the jury room waiting to be called up.

Our modern climate no longer affords us the luxury of credibility from the start. It’s something we have to earn and maintain now. So, if you couple this initial distrust with claiming an attenuated future wage-loss claim in opening statement that smells fishy, it’s going to be over before it even gets started. Especially when the defense then fuels that fire with convincing documents that demonstrate you’re overreaching. As soon as you let this mixture cement, the jurors then start scrutinizing areas of your case that actually have merit.

Thus begins the downward spiral that leads you to asking yourself the questions posed in the beginning of this article. This is also why insurance carriers typically low-ball attorneys who are making bogus claims even if other parts of the case have merit.

So, if you’re in the “let’s just throw it all up and see what sticks,” group and you don’t get the result you expected, please don’t blame the jury.

Let me give you an example of the perspective of the “let’s just throw it all up and see what sticks” group that causes misevaluation of what to claim at trial. Every time I mention to a referring attorney that I’m throwing out the life-care plan, stipulating to the defense’s billing numbers, acknowledging 25% comparative fault on the part of the plaintiff, not putting on any evidence of a future surgery recommendation even if the expert was already paid to testify to it and that all I’m going to do is put up the hard numbers, spend good time on the defendant’s conduct and plaintiff’s non-economic damages, a common theme quickly arises: They’re silent for a moment as they ponder all the money they spent on these things in the last two years that I just trashed in 30 seconds followed by the same recurring eruption. Their face begins to grimace as they look at me and exclaim:

“What?!? Bro, are you crazy? We spent a ton of money on that life care plan! We paid that doctor a lot of money to testify to the need for a future surgery and causation! Our medical biller was really expensive. We have to go with their numbers. We can’t acknowledge comparative fault, we have an expert who says otherwise that we paid, just let the jury find it on their own if they want to! Our mediator said this is a good strategy and also said that it’s our life-care plan that gives the case its value, so what are you talking about?!”

You get the point.

My response is always the same: “Listen, you came to me to try the case, I didn’t come to you. If you believe you’ve correctly evaluated what you want to sell the jury, go try the case yourself the way you’re describing and text me if you win. Otherwise, I’m going to stick with my evaluation, thank you very much. That’s why you came to me isn’t it?” Thankfully, most of the time, this generates an “OK, fine. Do what you think is right, we trust you” response.

What is the jury inclined to believe?

We must understand that evaluation doesn’t have a side, nor does it care about who wins. The only thing evaluation is concerned with is what most of society (nine out of 12 people) is inclined to believe based on their values and belief systems. This is hard to do for many of us because it goes against the grain of our fiber.

By the time trial rolls around, we’ve been duped into spending thousands to mediate only to get an opening offer of five grand on a $450,000 case after two hours of sitting there, having discovery hidden from us, insurance policies not initially disclosed, defense experts paid to lie and not answer questions at deposition; and the list goes on. Such that, by the time trial comes around, we’re so enraged by these tactics that it becomes personal.

This is especially true when the defense has the audacity to engage in this type of behavior with that smug smile because they’re getting paid hourly, while knowing that you’re spending tens of thousands of dollars trying to find things they’ve hidden. And when we express frustration because the defendant has been coached not to answer questions in depo, we get accused of harassing the witness and not being civil. This type of gas-lighting is enough to drive even the most proficient meditator crazy, right?

All I can say here is that all this anger, frustration, hostility and disappointment must be shed with the close of discovery. The pre-trial evaluation and the trial itself are no place for these types of emotions. Jurors can sense it, so you need to be at peace with it all as soon as discovery is closed and the next phase begins.

Last step – Make sure your evaluation is spot on to avoid surprises

Nowadays, you can do a focus group for $2,000 or less. It baffles me to hear people say, “We didn’t do it because the case wasn’t big enough,” or “They’re too expensive,” or the best one of yet, “We didn’t do it because they’re not accurate.” I’ll say this, if two focus groups reach basically the same result, your actual jury is extremely likely to reach the same result with moderate variability. Therefore, before every trial, I put on a fair presentation with admissible evidence and test my case every time, and twice on Sunday. Focus groups are now as indispensable to my recipe as salt and pepper is to a chef!

Oh, that reminds me!

Recipe for winning

Gather all of these ingredients:

1 cup decent plaintiff and facts

2 cups insurance company screw-up (this can be found almost anywhere)

3 cups good-quality evaluation

4 cups focus group (this is a must to make sure the above three ingredients are right).

Top this off with:

1 heaping quart of courage sprinkled with focus, principle and resolve. (You can’t get this ingredient on Amazon. This is only found in the wild).

Mix all these together by hand and the result is a good one every time. Please try it and send me a review.

Good luck and thank you.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine