Section 1981

A reason to consider federal court in employment race-discrimination cases

In determining whether to litigate an employment race-discrimination case in state or federal court, plaintiff’s counsel must not only consider the advantages offered by state court, but also assess the different rights and remedies afforded by state and federal anti-discrimination statutes. While generally, the cost-benefit analysis weighs in favor of staying in state court, there are occasions when including a Section 1981 claim (which likely means you will be removed to federal court) is the best strategy for your case.

This article will outline the procedural advantages of litigating an employment race-discrimination case in California state court versus federal court. It provides a brief overview and comparison between the key California anti-discrimination statute, the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA), and two federal statutes, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII) and Section 1981 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (Section 1981). In comparing the statutes, the article highlights parts of Section 1981 to show that in some cases asserting it may be the best option, even if it means the case will be heard in federal court.

Key advantages of litigating an employment race-discrimination case in state court

Filing only state claims (while avoiding diversity) means a plaintiff’s case will be heard in state court. While state courts can hear federal claims, if you include federal claims, the defendant is likely to remove the case to federal court.

There are several advantages to litigating in California state court instead of federal court, including the following:

The option to use a peremptory challenge to disqualify one judge without a showing of cause (Code Civ. Proc., § 170.6);

More discovery (federal court limits depositions to 10 per party, to a one-day, seven-hour deposition per witness, and to 25 written interrogatories per party unless you have leave of court);

More time to oppose summary-judgment motions (Code Civ. Proc., § 437, subd. (c). provides for 75 days’ notice before the hearing, while Fed. Rules Civ. Proc., rule 6(c)(1) provides for 14 days’ notice before the hearing);

Better juries (California state jurors are selected from a more representative cross-section of the population such as California Department of Motor Vehicle’s records, while federal court selects jurors only from voter registration records);

More voir dire (federal courts may prohibit attorneys from conducting any voir dire, while attorneys in state court have a right to question prospective jurors);

State court only requires three-fourths of the jurors to agree on a verdict (Code Civ. Proc., § 613), while federal court requires a unanimous jury verdict for a plaintiff to prevail (Fed. Rules Civ. Proc., rule 48); and

California state courts have substantial discretion in increasing the amount of attorney’s fees awarded including taking into account the risks associated with a contingency case. (See Graham v. DaimlerChryler Corp. (2004) 34 Cal.4th 553.) In federal court, fee-shifting statutes do not allow for increasing attorney’s fee awards because the case is on contingency. (McElwaine v. US West Inc. (9th Cir. 1999) 176 F.3d 1167, 1173.)

Choosing your forum: State and/or federal anti-discrimination statute?

Aside from the procedural advantages offered by state court in California, a plaintiff in an employment race-discrimination case generally still prefers filing the case under state law rather than federal law because the state’s principal anti-discrimination statute, the FEHA, is more favorable to plaintiffs than its federal counterpart, Title VII. However, an often-underutilized statute that should also be considered in race discrimination, race harassment and retaliation for complaining of such conduct, is Section 1981. Because of some of the advantages it offers, Section 1981 can be useful even though the case will likely be removed to federal court.

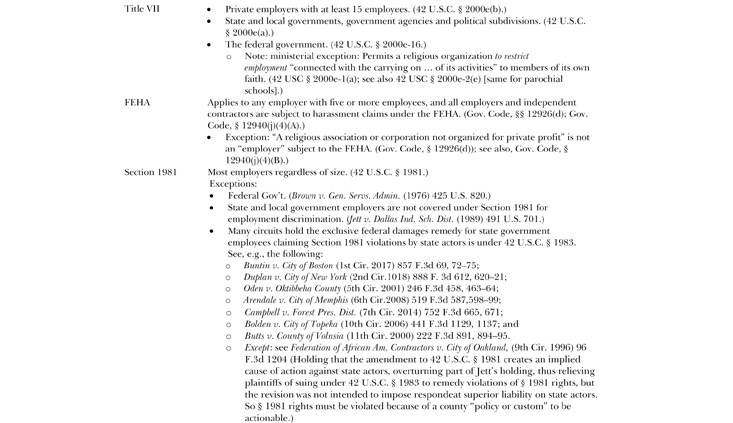

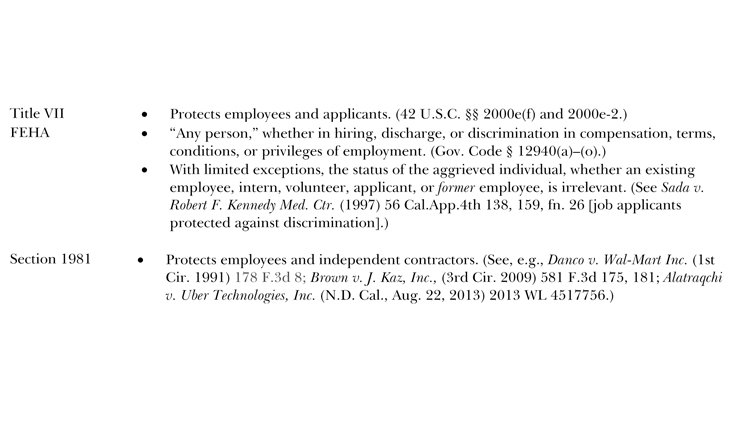

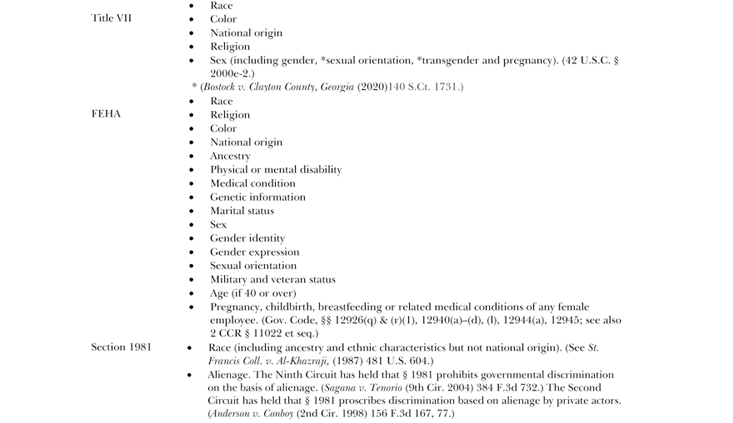

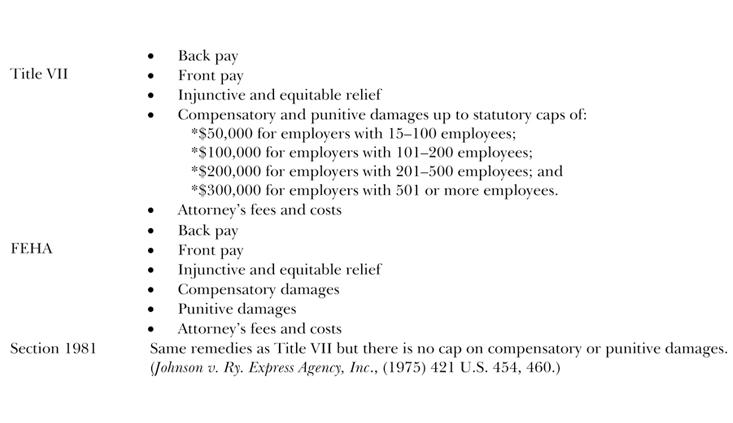

While these three statutes are similar, and the same set of facts may generally be pursued under each of them simultaneously, they remain separate and distinct causes of action. It is, therefore, important to know how the differences in the statutes can help or hurt your case. The following is a brief overview of each statute.

The California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA)

FEHA is the primary state law that provides persons with protection from discrimination, retaliation and harassment in employment based on several categories: race, religion, color, national origin, ancestry, physical or mental disability, medical condition, genetic information, marital status, sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, military and veteran status, age, and pregnancy, childbirth, breastfeeding or related medical conditions of any female employee. (Gov. Code, §§ 12926(q) & (r)(1), 12940(a)-(d), (l), 12944(a), 12945; see also 2 CCR § 11022 et seq.) The FEHA also prohibits retaliation against any person for making a complaint under the FEHA, for assisting another in making such a complaint or for opposing any action in the workplace that would constitute a violation of the FEHA.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII)

Title VII is the primary federal counterpart to FEHA. It generally makes it illegal to discriminate against an employee on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, or sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation. (42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2; Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia (2020) 140 S.Ct. 1731.) The law also makes it illegal to retaliate against a person because the person complained about discrimination, filed a charge of discrimination, or participated in an employment discrimination investigation or lawsuit.

42 U.S.C. Section 1981 (Section 1981)

Originally included as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Section 1981(a) states in relevant part: “All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.”

Broadly, although all three statutes prohibit discrimination in employment based on race, there are differences between these laws that can affect your case significantly.

Highlights of some of the useful provisions of Section 1981

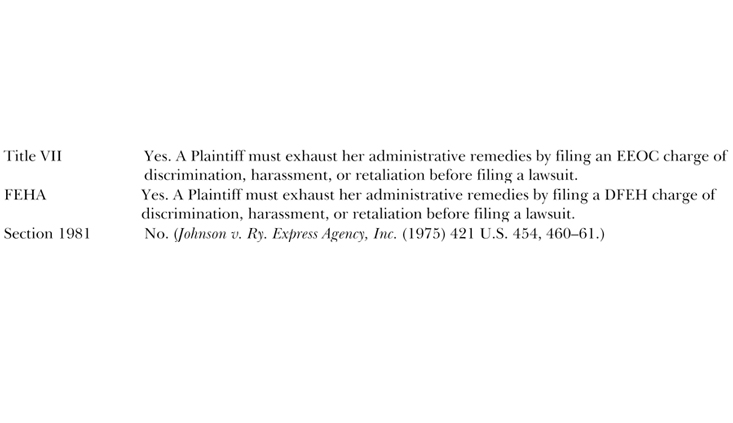

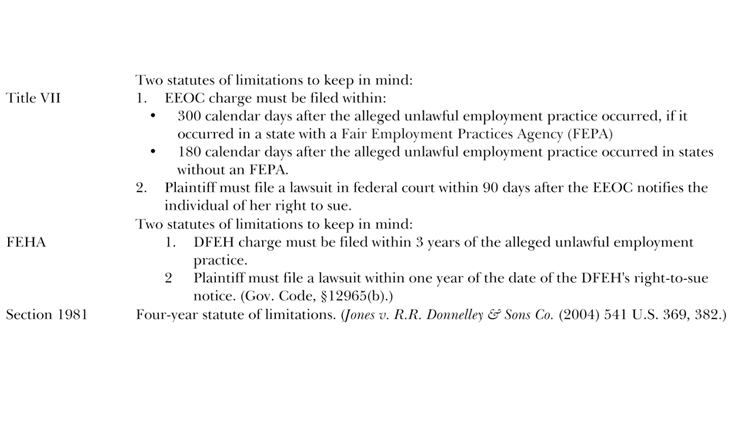

A comparison of six provisions of FEHA, Title VII and Section 1981 highlights how including a Section 1981 claim can help a plaintiff’s employment race-discrimination case.

Conclusion

In California, for both procedural and substantive reasons, it is generally more advantageous for a plaintiff in an employment race-discrimination case to select state court rather than federal court.

Despite the benefits of litigating in state court, in certain cases – such as when the time to exhaust an administrative remedy has lapsed, a person is an independent contractor, or when a longer statute of limitations is needed – asserting a Section 1981 claim may be a good option, or even the only option. Bringing, or including, a Section 1981 claim will almost inevitably mean the case will be removed to federal court.

In determining whether to litigate in state or federal court, plaintiff’s counsel, in consultation with the client, should carefully consider the specific facts and legal circumstances of each case.

María G. Díaz

María G. Díaz is the founder of The Diaz Law Firm and serves as Of Counsel to the law firm of Allred, Maroko & Goldberg. She has dedicated her legal career to representing workers in a range of employment matters. Ms. Díaz currently serves on the board of the California Employment Lawyers Association (“CELA”) and the Latina Lawyers Bar Association (“LLBA”). Ms. Díaz holds a bachelor’s degree in quantitative economics from Stanford University, a master in public policy from Harvard University, and a J.D. from Stanford Law School. She studied at Princeton as a Woodrow Wilson National Fellow.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine