Cracking the corporate shell game to find deeper pockets

Transportation companies: Establishing shared liability through joint-venture and single-business-enterprise theories

Transportation companies of all stripes attempt to shield assets from liabilities. They often do so by spending top dollar on Big Law transactional lawyers to set up complex corporate structures. And some of the carriers that insure them use this as an opportunity to avoid coverage. Attempting to demonstrate to a court that these corporate structures are illegitimate is usually an uphill battle because, quite frankly, nobody understands what is going on or why. Rather than engaging in the tortuous task of trying to unwind these entities, there is an easier way: Embrace them and show that they are all liable using joint-venture or business-enterprise theories.

California law has long held that in certain scenarios, principles of equity and justice may require that liability be shared between entities. Two specific types of shared liability theories are joint-venture and single-business enterprises. Those shared-liability theories may apply where an entity has committed a tort and the entity appears to be part of a larger enterprise. Under these theories, other entities within the venture or enterprise may be jointly responsible for the tortious conduct.

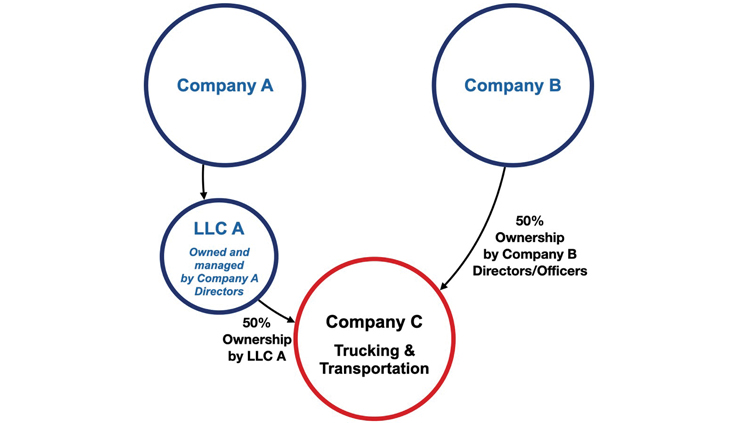

Consider the following situation. A truck transporting goods causes a significant collision, leading to grave injuries to people in other vehicles. The truck is owned by Company C, and it is transporting goods for Company A. As it turns out, Company C is an entity owned equally by Company B and LLC A. Years ago, Company B provided significant trucking services to Company A. Then one day, the executives of Company A approached Company B with an idea – let’s create Company C to be the exclusive trucking provider for Company A. The idea was to reduce costs and make everyone more efficient. Company A forms LLC A, where the members are the people that run Company A. Then LLC A and Company B formally create Company C.

That is just one example of a factual scenario where joint-venture or single-business enterprise theory may result in members to a joint venture or single business enterprise having shared liability for the truck accident caused by the Company C truck.

This article explores those theories of shared liability and provides some strategies of how to prove your case.

California law on joint venture

Joint venture is a theory of shared liability. It is not a crime or a separate tort. California law has long recognized that the joint venture and each of its members are vicariously liable for the torts of an employee acting in furtherance of the venture. (Leming v. Oilfields Trucking Co. (1955) 44 Cal.2d 343, 350.) California caselaw has described joint venture as having several elements, while the current California Civil Jury Instruction 3712 has four elements. Regardless of whether it is three versus four elements, the components of joint venture are the same.

California law defines a joint venture as an undertaking by two or more entities to combine their property, skill, or knowledge to carry out a single business enterprise for profit. (Holtz v. United Plumbing and Heating Co. (1957) 49 Cal.2d 501, 506.) Historically, California caselaw describes a joint venture as having three elements: 1) each member must have an ownership interest in the venture; 2) the members must have joint control over the business; and 3) the members must share the profits and losses of the business. (Orosco v. Sun-Diamond Corp. (1997) 51 Cal.App.4th 1659, 1666; see also Simmons v. Ware (2013) 213 Cal.App.4th 1035, 1056 [right of joint participation in the management of business may satisfy joint control element]; Buck v. Standard Oil Co. of Cal. (1958) 157 Cal.App.2d 230, 240 [“Joint venturers may delegate responsibility between them for certain portions of the job without destroying the joint venture aspect thereof”].)

The California Civil Jury Instructions on joint venture have the same components, but describes the components as four elements:

1) Two or more persons or business entities combine their property, skill, or knowledge with the intent to carry out a single business undertaking;

2) Each has an ownership interest in the business;

3) They have joint control over the business, even if they agree to delegate control; and

4) They agree to share the profits and losses of the business.

(CACI No. 3712).

Those elements must be met, and merely some connection between two entities is not sufficient in and of itself. For example, a company that leases a truck from Penske does not create a joint venture between the company and Penske. (See Jeld-Wen, Inc. v. Superior Court (2005) 131 Cal.App.4th 853, 872-73; Myrick v. Mastagni (2010) 185 Cal.App.4th 1082, 1091 [“[i]t should be obvious that a truck leasing company is not in a joint venture with everyone to whom it leases a truck”].)

The first element within CACI 3712 refers to a “single business undertaking.” A common misconception is that only a single business transaction or undertaking can be a joint venture. California law has long recognized that “a joint venture may be of longer duration and greater complexity than a partnership.” (Weiner v. Fleischman (1991) 54 Cal.3d 476, 482.) Though the intention of the parties is relevant, a joint venture may be “assumed to have been organized from a reasonable deduction from the acts and declarations of the parties.” (Swanson v. Siem (1932) 124 Cal.App. 519, 524; see also Unruh-Haxton v. Regents of University of California (2008) 162 Cal.App.4th 343, 370.)

Corporations or limited-liability companies, or some other form of business association, may be parties to a joint venture. The fact they are corporations or limited-liability companies does not prevent them from being members of a joint venture. The identity of the members to a joint venture is not erased by the existence of the joint venture. (Cochrum v. Costa Victoria Healthcare, LLC (2018) 25 Cal.App.5th 1034, 1053 [corporation that owned a skilled nursing facility and limited liability company that operated the facility found to be in a joint venture for purposes of tort liability to facility patient].)

When the evidence of a joint venture is disputed, then the existence or nonexistence of a joint venture is a question of fact for the jury to decide. (See Unruh-Haxton v. Regents of University of California (2008) 162 Cal.App.4th 343, 370.)

Single-business enterprise and alter ego

Single-business enterprise theory is a form of alter ego. Under the theory, a court may disregard the corporate or other business association form and hold one or more corporation or entities liable for the debts of an affiliated entity when the affiliated entity “‘is so organized and controlled, and its affairs are so conducted, as to make it merely an instrumentality, agency, conduit, or adjunct of another corporation.’” (Las Palmas Associates v. Las Palmas Center Associates (1991) 235 Cal.App.3d 1220, 1249 (internal citation omitted) (hereafter Las Palmas Associates).)

Where allegedly separate entities “operate with integrated resources in pursuit of a single business purpose, those entities are single business enterprise.” (See Toho-Towa Co., Ltd. v. Moran Creek Productions, Inc. (2013) 217 Cal.App.4th 1096, 1107-08 (hereafter Toho-Towa Co.).) Accordingly, the entities to an enterprise may all be jointly liable for the tort of one of the entities.

From a policy perspective, single- business enterprise theory addresses unjust circumstances. “[I]t would be unjust to permit those who control companies to treat them as a single or unitary enterprise and then assert their corporate separateness in order to commit frauds and other misdeeds with impunity.” (Las Palmas Associates, supra, Cal.App.3d at page 1249.)

“[W]here there is ‘such domination of finances, policies and practices that the controlled corporation has, so to speak, no separate mind, will or existence of its own and is but a business conduit for its principal,’ the affiliated corporations may be deemed to be a single business enterprise, and the corporate veil pierced.” (Toho-Towa Co., supra, 217 Cal.App.4th at page 1107 [quoting and citing 1 Fletcher Cyclopedia of the Law of Corporations § 43].)

The single-business-enterprise theory is an equitable doctrine applied to reflect partnership-type liability principles when corporations integrate their resources and operations to achieve a common business purpose. (Toho-Towa Co., supra., 217 Cal.App.4th at page 1108.) The analysis is often case-specific. Because single-enterprise theory is based upon equitable principles, the existence is of a single enterprise ‘“is not made to depend upon prior decisions involving factual situations which appear to be similar”’ but rather depend upon the conditions ‘“according to the circumstances of each case.”’ (Ibid. [quoting McLoughlin v. L. Bloom Sons Co., Inc., 206 Cal.App.2d 848, 853].) “It is the general rule that the conditions under which a corporate entity may be disregarded vary according to the circumstances of each case.” (Automotriz v. Resnick (1957) 47 Cal.2d 792, 796.)

The issue is not whether the corporate entity should be disregarded for all purposes, but whether under the specific circumstances “justice and equity can best be accomplished and fraud and unfairness defeated by a disregard of the distinct entity of the corporate form.” (Kohn v. Kohn (1950) 95 Cal.App.2d 708, 718.)

There are two requirements to invoke the doctrine of single-business enterprise: “(1) such a unity of interest and ownership that the separate corporate personalities are merged, so that one corporation is a mere adjunct of another or the two companies form a single enterprise; and (2) an inequitable result if the acts in question are treated as those of one corporation alone.” (Tran v. Farmers (2002) 104 Cal.App.4th 1202, 1219.) Whether those requirements have been satisfied is a question of fact. (Las Palmas Associates, supra, 235 Cal.App.3d at page 1248.) The facts of a case are considered against a variety of potential factors.

In Marr v. Postal Union Life Ins. Co. (1940) 40 Cal.App.2d 673, 682, the relevant factors were the following: A new corporation engaged in practically no independent business; its work was performed by employees of the parent company, the new and parent corporation employing the same attorney; the corporations uses the common offices owned and furnished by the parent; and in a complaint in a prior action the parent had alleged that the new corporation was its agent.

In other cases, “factors for the trial court to consider include the commingling of funds and assets of the two entities, identical equitable ownership in the two entities, use of the same offices and employees, disregard of corporate formalities, identical directors and officers, and use of one as a mere shell or conduit for the affairs of the other”…, and “the courts must look at all the circumstances to determine whether the doctrine should be applied.” (Toho-Towa Co., supra., 217 Cal.App.4th at page 1108-09 [quoting Troyk v. Farmers Group, Inc. (2009) 171 Cal.App.4th 1305, 1341-1342]; see also Associated Vendors, Inc. v. Oakland Meat Co., Inc. (1962) 210 Cal.App.2d 825, 839-840.)

No single factor is determinative, and not all factors need apply. The court must look at all the circumstances to determine whether the theory should apply. (Sonora Diamond Corp. v. Superior Court (2000) 83 Cal.App.4th 523, 539.)

Discovery strategies in cases with shared-liability theories

These shared liability theories are driven by the facts of the specific case. Early in your case, think beyond how the elements are written. Instead, think about how the elements and factors of joint venture or single business enterprise could manifest in real life given your understanding of how your target entities operate.

For example, both theories include the concept of control. Accordingly, for control, consider how the entities may exercise control. There are multiple ways control may be exercised through common business functions. Core business functions include administration, finances, general management, human resources, marketing, production, and purchasing, as well as potentially others, depending on the type of business. Each business function can be rich in evidence useful in proving these theories. So, spend time thinking about the core business functions of the entities in your case, and then serve focused discovery on those functions.

One core business function is administration. Every business must administer payroll to employees, pay bills to service providers, figure out insurance coverage for liability, property, and employees. A business may need utilities and technology to function. Discovery can seek documents and information regarding who is administering the existence of internet services, business cell phones, office supplies, water in the common kitchen area, and janitorial services for the offices, and the list goes on. Though detailed, these areas can be ripe with examples of joint control, management, and sharing of resources.

Financial management and finances of the entities are also relevant to both joint-venture and single-business enterprise theories. Written discovery should seek documents and information regarding those topics. The entities will surely object and refuse to provide information, but the information and documents are relevant and any need for confidentiality can be satisfied with a protective order.

Another factor is conduit for the affairs of the other, which is similar to the concept of a common business undertaking. For example, a trucking company – Company C – may own 20 trucks on paper but employs no drivers. The drivers instead come from a second entity – Company B. Those Company B drivers then operate the 20 Company C trucks to transport nearly 100% of goods produced by another entity – Company A. Each of those entities is arguably a conduit for the affairs of the others. What may further strengthen that contention is that Company A (needs the goods transported) and Company B (has drivers but no trucks) together own Company C (has trucks but no drivers and no goods to transport).

Those are but some examples of categories and factors. Overall, discovery tools should be custom crafted for the circumstances of your case. After all, the viability of these shared liability theories depends on the circumstances of the case.

Common discovery topics

There are some general topics of inquiry in discovery that may be sought in any joint venture or single business enterprise. Some common discovery topics include:

Identification of information and documents regarding all of the officers, managers, members, and directors of each entity;Identification of information and documents regarding how each entity generates revenue, including the revenue per customer numbers or percentages for each entity (i.e., Company C derives 99% of its revenue from Company A);Identification of information and documents regarding all contracts and agreements for the work the entity performs, along with contracts and agreements between the entities alleged to be part of the joint venture or single business enterprise;Identification of information and documents regarding who performs the accounting services for the entity;Identification of information and documents regarding who performs the administrative services for the entity;Identification of information and documents regarding determination and acquisition of insurance for each entity;Identification of information and documents regarding each office, facility, or property that the business owns, leases, uses, or occupies;Identification of information and documents regarding business management meetings, including but not limited to shareholder/board member meetings, which may occur annually or multiple times per year; andIdentification of information and documents regarding loans that the entity had, including information about collateral for loans and who guaranteed the loans.

Each of those topics can be split into multiple, particularized requests. For example, the discovery requests regarding administration can be particularized into specific administrative functions, examples of which are previously addressed in this article – e.g., utility acquisition and payment, business cell phones, human resources, etc.

The requests should include a reasonable period of time that encompasses the incident date. So, if a case arises from a trucking incident in 2020, the period of time should begin prior to the incident and end after the incident. It would certainly be unusual if a business changes its practices on the day of the incident. Of course, that is another area of inquiry – the changes to how a business operates following the incident. Lastly, depending on your case, the time of creation of the joint-venture entity of part of the single enterprise may also be relevant to your case, so consider that when identifying your relevant period of time in the requests.

Take focused corporate-entity-witness depositions

As many practitioners know, conducting corporate-entity-witness depositions is a critical step in case development and one best taken after obtaining some information and materials in written discovery. The depositions of persons- most-qualified (PMQ) are critical in proving shared liability theories. (Code Civ. Proc., § 2025.230.)

Given the importance of these depositions, it’s worthwhile to take time to carefully craft the topics within a PMQ deposition notice. In a notice from a recent matter, we had 90-plus deposition topics. The topics were generated from facts specific to our case, using core business functions as a larger method of organization. We had multiple, particularized topics that addressed specific areas of business administration that we believed were examples of joint control and use of same offices and employees.

Here is a generalized list of the deposition topics to consider for entity depositions:

administration and management of the entity generally, including entity creation and board meetings;

management and administration services – office space, office supplies, utilities, mail services, amenities, phones, in-house legal services, written agreements for such topics, preparation of such written agreements, board meetings, identities and roles of owners/shareholders/members, identities and roles of directors/officers, parent companies and/or subsidiaries of entities;

employee services – payroll, human resources, IT support, email addresses and hosts, workers compensation, insurance, computer software subscriptions, cell phones, location and custodian of email servers;

internet presence – website, social media, ownership and registration of domain names;

finances – total revenue, operating costs, revenue by customer, earnings distributions, financial dependence between entities (i.e., how much of entity X’s total business revenue is derived from entity Y), accounting services;

safety and rules – standard operating procedures or rules including who drafted the rules and who had to follow, cross-over of rule applicability between entities, training, disciplinary actions and structure of review;

the specific incident – approval process for use of vehicle or activity, disciplinary actions, who responded to incident, communications between members of the allegedly different entities regarding the incident.

Including broad topics as well is a good idea. Such topics as “the nature of the business relationship between company A and LLC A” or “Administration services provided to Company A,” are good because despite preparation and carefully crafting a topic list, new information about something you did not think of may arise in an entity deposition.

Organizing the evidence and using visual storytelling

These shared liability theories can be complex and fact heavy. As the evidence develops, take time to organize it. Making lists or grouping evidence based upon elements or topic area can be helpful in framing the issues, preparing for and taking additional depositions, and being ready for the eventual motions for summary adjudication or judgment. By organizing the evidence as you develop it, a separate statement can be easier to write in a manner that presents the evidence simply and logically, a task that may otherwise be a complex and difficult to organize.

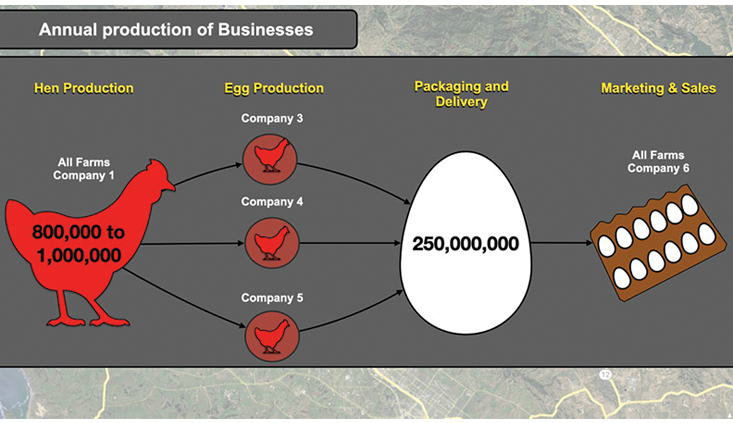

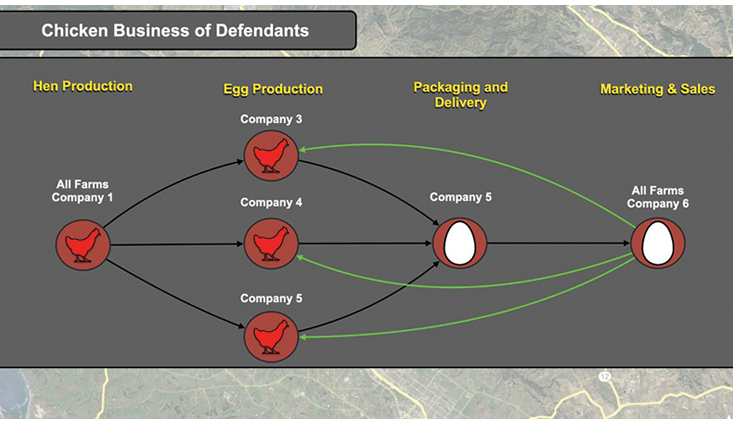

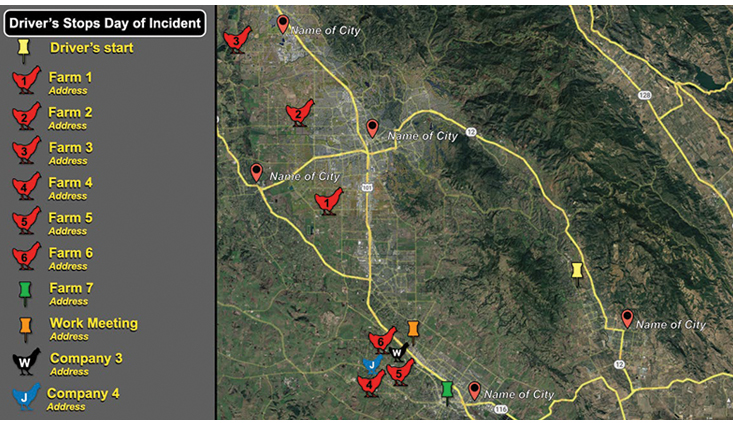

Organizing the evidence may also aid in the development of visuals for use in pre-trial discovery. Creating visuals from complex information, learned discovery and deposition results is powerful evidence that makes things simpler. Some useful visuals to consider are the creation of organizational charts and diagrams to show the overlap of directors, officers, or owners. Other good visuals may be diagrams that show how a business is managed or how a group of entities are part of the same supply chain. Generating maps that demonstrate where the driver who caused a collision drove earlier in the day may be good for showing the inter- connectedness between entities.

Visuals do not need to only incorporate evidence learned in the case. Visuals can utilize Google maps or street-level views, or other publicly available information. The Google maps and publicly available information can be authenticated, with appropriate foundation laid, in depositions of party-opponent witnesses. If possible, try creating the visuals prior to key entity depositions. Doing so allows for the visuals to be used in those depositions. If the information in the visuals conforms to evidence in the case, then the witness may have no choice but to confirm the visual is accurate. See our examples above of visuals that were utilized in a case involving these shared-liability theories (specific party information has been removed):

A map to show where the driver who caused a collision drove on the day of the incident.A flowchart that shows the annual production of multiple allegedly separate entities and how the entities were dependent on each other.A flowchart that shows how the allegedly separate entities were part of a joint venture and single enterprise, with revenue flowing back from marketing and sales to the others.

Think big and aim small to hit your target

Cases with joint-venture or single- business enterprise are always unique in some respect given the entities involved. Think big when considering how the entities may work together, co-manage, and ultimately gain an advantage from the way its venture or enterprise is arranged. As you think big, develop a list of ideas or topics that fit within the larger framework of what must be proved to prevail on these shared-liability theories. Then ultimately approach discovery by aiming small, targeting specific areas of detail and evidence that fits within the elements or factors. Often, you will find weaknesses in defense’s case where it would make practical business sense for the defense entities to be more efficient or to reduce costs. For example: Why create a new accounting group for the trucking company, Company C, when Company A and Company B have established accounting groups that can shoulder the additional accounting work together? Why start a new IT department when one already exists within the enterprise?

These issues are always discovery and fact heavy, but putting in the work can lead to results. More importantly, it can lead to accomplishing justice and equity.

Matthew Stumpf

Matthew Stumpf is a trial attorney with Panish | Shea | Boyle | Ravipudi LLP, where he dedicates his practice to representing people in complex and catastrophic personal injury, wrongful death, and aviation cases. Matthew may be reached by email at mstumpf@psbr.law.

Kevin Boyle

Kevin Boyle is a co-founder and partner with Panish | Shea | Boyle | Ravipudi LLP. Kevin specializes in resolving large, high-profile plaintiff cases by trial or settlement including wrongful death, catastrophic personal injury, aviation and train incidents, sexual assault and abuse as well as cases of serious fraud. Kevin may be reached by email at kboyle@psbr.law.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine