Unwinding the statute-of-limitations clock

Using the delayed-discovery rule to save your case

You have a new case you want to take on – it’s a just cause and the damages are significant. But there is a big problem. Your client was harmed more than two years ago, and the case may be barred by the statute of limitations. Before you automatically decline the case, consider California’s delayed-discovery rule. Under the right circumstances, this rule can be a powerful tool to help your client unwind the statute of limitations clock and achieve a just outcome on the merits.

The delayed-discovery rule is very useful in cases involving exposure to toxic substances, but as described in this article it can also apply to almost any other type of case as well, including product liability, sexual abuse and assault, cases involving fraud, defamation, and even breach of contract. This article addresses these and other circumstances to unwind the statute of limitations clock and to save your case.

The delayed-discovery rule

In some instances, a plaintiff may sustain injuries without realizing it for years. Other times, a plaintiff may know they are injured but remain unaware of the cause. Finally, a plaintiff may not know that their injury was caused by wrongdoing – this can be a particularly powerful tool to save your case in many contexts. For example, in the product liability context where a design or manufacturing defect may not be reasonably apparent.

Barring such cases under the statute-of-limitations defense would be unfair and a mockery of our civil justice system. It would enable wrongdoers to escape the consequences of their actions simply because the injury took some time to manifest itself or because the wrongdoer was skilled at concealing their wrongful conduct.

California courts recognize the inherent unfairness of barring such cases. The delayed-discovery rule provides that the statute of limitations clock does not start running until plaintiff should have been aware of the injury, its cause, and reasonable notice that the injury was caused by wrongdoing.

Exposure to toxic chemicals/pollutants

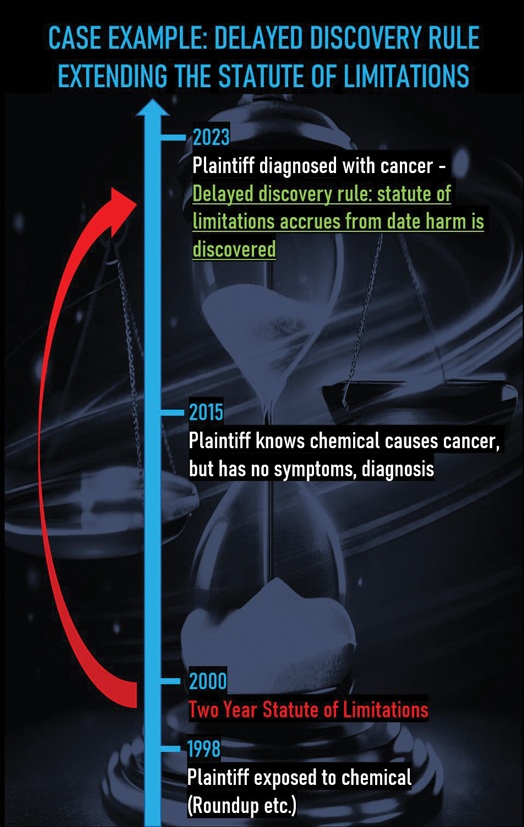

The interval between exposure to a toxic chemical (for example, Roundup) and development of a disease (such as cancer) can often span a decade or more. The delayed-discovery rule plays a crucial role in preventing such cases from being time-barred. Code of Civil Procedure section 340.8, subdivision (a) codifies the chemical-exposure delayed-discovery rule: “In any civil action for injury or illness based upon exposure to a hazardous material or toxic substance, the time for commencement of the action shall be no later than either two years from the date of injury, or two years after the plaintiff becomes aware of, or reasonably should have become aware of, (1) an injury, (2) the physical cause of the injury, and (3) sufficient facts to put a reasonable person on inquiry notice that the injury was caused or contributed to by the wrongful act of another, whichever occurs later.” (Emphasis added).

Therefore, if a plaintiff was exposed to a toxic chemical 20 years ago, but the plaintiff was not diagnosed with cancer until the last two years, the delayed-discovery rule can overcome the statute of limitations defense.

However, even if the claimed medical condition began more than two years ago, what if the plaintiff did not know that their injury was caused by toxic exposure or wrongdoing? Under these circumstances, the claim may remain timely if the plaintiff can show a reasonable lack of knowledge of either (1) the cause of the injury or (2) that the injury was caused by wrongdoing.

Additionally, a progressive disease that occurs over time may only accrue when plaintiff suffers “actual and appreciable harm.” (San Francisco Unified School Dist. v. W.R. Grace & Co. Conn. (1995) 37 Cal.App.4th 1318, 1327-1331.) A threat of unrealized future harm such as a one-in-four chance of contracting a serious disease may also be insufficient to trigger accrual. (New v. Armour Pharmaceutical Co. (9th Cir. 1995) 67 F.3d 716, 721-722 (overruled on other grounds).)

Significantly, two or more injuries that are qualitatively different (i.e., COPD versus lung cancer from smoking) may accrue at different times and be subject to their own statute of limitations. (Pooshs v. Philip Morris USA, Inc. (2011) 51 Cal.App.4th 788, 799-802.)

While one common defense in toxic-exposure cases is to argue plaintiff should have had knowledge of the cause of their harm due to media reports, in California such media reports alone are not sufficient under C.C.P. section 340.8, subdivision (c) (2): “Media reports regarding the hazardous material or toxic substance contamination do not, in and of themselves, constitute sufficient facts to put a reasonable person on inquiry notice that the injury or death was caused or contributed to by the wrongful act of another.”

Products liability

The delayed-discovery rule may be applied to great effect in product-liability cases, since the statute of limitations clock may not begin to run until plaintiff suspects that a product defect caused their injury. In Clark v. Baxter Healthcare Corp. (2000) 83 Cal.App.4th 1048, the plaintiff nurse sued a latex glove manufacturer. The court found that her cause of action did not necessarily accrue when she first experienced allergic reactions due to wearing the gloves. At that time, plaintiff had no reason to believe she had anything more than a natural allergy. Instead, her action accrued when she had reason to believe her injury could be caused by a manufacturing defect or other wrongdoing by defendants, such as allergies attributable to the manufacturing process of the gloves. (Id. 1058-1060.) Indeed, “if a plaintiff’s reasonable and diligent investigation discloses only one kind of wrongdoing when the injury was actually caused by tortious conduct of a wholly different sort, the discovery rule postpones accrual of the statute of limitations on the newly discovered claim.” (Fox v. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. (2005) 35 Cal.4th 797, 813.)

For example, a plaintiff injured during surgery may be imputed with knowledge of medical malpractice by the surgeon but not of a products-liability claim against the manufacturer of an implanted medical device. Under those facts, if plaintiff’s reasonable and diligent examination does not reveal the basis for the product liability claim, its accrual is delayed until plaintiff has a reason to suspect the injury resulted from the defective product. (Id. at 813-815.)

Sexual abuse and assault

The delayed-discovery rule has been codified and extended by 2019 amendments to C.C.P. section 340.1 for sexual- abuse cases. These amendments have substantially extended the applicable statute of limitations periods for such cases. For childhood sexual abuse and assault, under C.C.P. section 340.1(a) such claims must ordinarily by brought “within five years of the date the plaintiff discovers or reasonably should have discovered that psychological injury or illness occurring after the age of majority was caused by the sexual assault” (or within 22 years of the date plaintiff attains the age of majority, if later).

For sexual assault for adults over the age of 18, such claims must be brought within the latter of “10 years from the date of the last act, attempted act, or assault with the intent to commit an act, of sexual assault,” or “[w]ithin three years from the date the plaintiff discovers or reasonably should have discovered that an injury or illness resulted from an act, attempted act, or assault with the intent to commit an act, of sexual assault by the defendant.” (See C.C.P. § 340.16.)

Cases involving fraud

The delayed-discovery rule has been codified by C.C.P. section 338(d) in cases involving fraud, and accrual of the three-year statute of limitations occurs upon “the discovery, by the aggrieved party, of the facts constituting the fraud or mistake.” If the defendant actively took steps to conceal the nature of the wrongdoing, plaintiff may use the doctrine of fraudulent concealment in combination with the delayed-discovery rule to further extend the statute of limitations.

Where defendant fraudulently concealed facts that would have led plaintiff to discover a potential cause of action, the cause of action is tolled until plaintiff actually discovers or is put on inquiry notice of the fraud. (Community Cause v. Boatwright (1981) 124 Cal.App.3d 888, 900-902.) In Regents of University of California v. Superior Court (1990) 20 Cal.4th 509, 533, the court held: “The doctrine of fraudulent concealment, which is judicially created, limits the typical statute of limitations. The defendant’s fraud in concealing a cause of action against him tolls the applicable statute of limitations.... In articulating the doctrine, the courts have had their purpose to disarm a defendant who, by his own deception, has caused a claim to become stale and a plaintiff dilatory.” (Quotations, citations omitted). Similarly, where defendant intentionally conceals their identity, they may be equitably estopped from asserting the statute of limitations. (Bernson v. Browning-Ferris Indus. of Calif., Inc. (1994) 7 Cal.4th 926, 936-937.)

Defamation cases

The delayed-discovery rule may also be applicable to a claim for defamation, especially where the defamation is occurring “behind plaintiff’s back.” In Manguso v. Oceanside Unified School District (1979) 88 Cal.App.3d 725, 727 plaintiff school-teacher sued the school district for libel for making defamatory statements about her in a letter in her confidential personnel file, which was ultimately shown and read to prospective employers. The letter was placed in the plaintiff’s personnel file in 1960, but she did not discover its existence until 1976. (Ibid.)

On appeal, the court applied the delayed-discovery rule to allow the plaintiff to bring her claim, stating, “[t]his (discovery rule) exception is based on the notion that statutes of limitations are intended to run against those who fail to exercise reasonable care in the protection and enforcement of their rights; therefore those statutes should not be interpreted so as to bar a victim of wrongful conduct from asserting a cause of action before he could reasonably be expected to discover its existence.” (Id. at 731 (quotations, citations omitted).)

Breach-of-contract actions

The delayed-discovery rule has been extended to breach-of-contract cases since “the delayed-discovery rule … applies when the injury or the act causing the injury is ‘difficult’ for the plaintiff to detect.” (Gryczman v. 4550 Pico Partners, Ltd. (2003) 107 Cal.App.4th 1, 5.) In Gryczman it was a question of fact whether plaintiff with a right of first refusal to purchase property was unaware that owner breached contract by conveyance to another person, despite the recordation of the conveyance. Similarly, in April Enterprises, Inc. v. KTTV (1983) 147 Cal.App.3d 805, it was a question of fact whether defendant breached a contract prohibiting the deletion of television program tapes when the tapes were in defendant’s exclusive control and the deletion occurred in secret. (Id. at 832-833.)

Other tools that can unwind the statute-of-limitations clock

Apart from the delayed-discovery rule, other tools can overcome the statute-of-limitations defense based on case-specific facts. For example, tolling of the statute of limitations may occur under various circumstances, including:

a minor plaintiff under the age of majority under C.C.P. § 352(a);

military personnel during service under 50 U.S.C. App. § 526(a);

a mentally incompetent plaintiff under C.C.P. § 352(a);

a plaintiff imprisoned on a criminal charge as set forth in C.C.P. § 352.1(a);

when the Court assumes jurisdiction over a “disabled” plaintiff attorney’s practice under C.C.P. § 353.1;

when the plaintiff dies under C.C.P. § 366.1;

when the defendant dies under C.C.P. § 366.2; and

where plaintiff is a potential member of an attempted class action – see American Pipe & Const. Co. v. Utah (1974) 414 U.S. 538, 552-553.

The above list is by no means exhaustive, and there are certainly other applications of the delayed-discovery rule.

Before you decline your next case based on a statute-of-limitations defense, carefully consider if one of these exceptions applies. Using these legal tools to unwind the statute of limitations clock can mean the difference between your client being wronged twice (first by the wrongdoer and second by the justice system), or alternatively, your client being given a fair chance to obtain a just result on the merits.

Robert Jarchi

Robert Jarchi won over nine figures in 100 days this year alone for his clients, and has won awards for much more over his 23-year career as an attorney and partner at Greene, Broillet & Wheeler. Rob’s practice includes brain injuries, toxic torts, burn injuries, and wrongful death matters.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine