Mop up the defense

Slip-and-fall discovery plans that include key admissions to use at trial

Slip-and-fall cases might seem straightforward on the surface: A plaintiff slips on a substance and falls down, causing injuries. But defendants will almost certainly put up a fight on liability, causation, and damages. Setting up a solid discovery plan from the get-go will assist you in not only obtaining the information you need to prove your case but can also provide you with key admissions to use at trial. This article will explore how to craft premises liability written discovery with an eye towards trial.

The initial round of written discovery

From establishing control to establishing notice to identifying witnesses and managers and early contentions, your first round of written discovery to defendants in a slip-and-fall case must cover a lot of ground.

Your first round of written discovery is your first chance to figure out who the key players are and get a clear picture of what actually happened. To that end, your priority should be identifying policies and procedures and other relevant documents, and identifying anyone with knowledge of how the incident works.

For every fact question you ask about in your special interrogatories, you should also ask the defendants to identify any documents and witnesses that support their answer. Have special interrogatories that make the defendants identify who had control of the area, who was supposed to inspect the area, who wrote the relevant policies and procedures.

The responses to these questions will identify the people you need to depose and the documents you need to request in your next round of discovery. Sometimes, these responses will identify additional culpable parties that you can DOE in.

Next, use your requests for production and special interrogatories to identify and ask for every policy, procedure, and training document that you can think of. Ask for safety policies, slip-and-fall prevention policies, inspection policies, and any other relevant type of policy you can come up with. Getting these documents early will help you prepare for depositions and help you find ways to expose the defendant’s bad policies and training practices.

Finally, be adamant about getting any surveillance footage of the incident. It is becoming surprisingly common for defendants to withhold surveillance footage or claim that none exists. Sometimes there may not be footage, but push back, anyways. Even if they dig their heels in, you can begin to position yourself for a spoliation instruction at trial.

Don’t skimp on the meet and confer

Almost universally, the first set of responses you receive back will be evasive and nonresponsive. Your opposing counsel will withhold responses based on a laundry list of objections and claim privilege over items where no such privilege exists. This happens simply because they usually get away with it.

A common example of this evasiveness is when defendants assert the work-product doctrine to withhold responses to Form Interrogatories 12.2 and 12.3. Coito v. Superior Ct. (2012) 54 Cal.4th 480, 502, held specifically that 12.3 requires a foundational showing by the responding party before any claim of the work product doctrine holds any merit – “instead, the interrogatory must usually be answered.” You are entitled to these witnesses’ identities.

Similarly, defendants will often object that your propounded contention questions call for a legal conclusion or expert opinion. However, these objections are improper under Rifkind v. Superior Ct. (1994) 22 Cal.App.4th 1255, 1261, which held that written interrogatories are the preferred method of obtaining information related to whether a party is making a contention, or to the facts, witnesses, and writings on which the contention is based.

Rifkind further held that, “an interrogatory is not objectionable because an answer to it involves an opinion or contention that related to fact or the application of law to fact or would be based on information obtained or legal theories developed in anticipation of litigation or in preparation for trial.” (Ibid.) Additionally, “a party to an action may not necessarily avoid responding to a request for admission on the ground that the request calls for expert opinion and the party does not know the answer.” (Bloxham v. Saldinger (2014) 228 Cal.App.4th 729, 751.) You are entitled to every contention that the defendant is making, as well as the facts, witnesses, and documents upon which they base that contention.

Therefore, it is necessary to prepare a meet-and-confer letter that covers everything. It’s tedious, it’s a pain, but it puts the ball back in the defendant’s court. Often, the defense will cave right away and produce sufficient responses.

In the instances where defendants push back on your initial meet and confer, the situation becomes more of a war of attrition than an argument about the Code of Civil Procedure. The fact of the matter is that case law on discovery is very clear; the Civil Discovery Act is meant to be liberally construed in favor of discovery. (Greyhound Corp. v. Superior Ct. (1961) 56 Cal.2d 355, 383.) Almost always, there is a way to fight for the information you are entitled to. Even if tedious, having this fight early on will set the tone and get you information that will be crucial to your case as litigation moves forward.

In Los Angeles, you will have to go to an Informal Discovery Conference (IDC) before you can file a motion to compel further responses. While this is an additional step in an already tedious process, IDCs give you an opportunity to hear what a judge has to say about any disputes. Each department handles things a bit differently, but getting input from a judge will often give you leverage against your opposing counsel and will likely end in the defendants producing whatever they had been withholding. There’s also the additional bonus of schadenfreude watching your opposing counsel get lectured if they’ve been needlessly evasive throughout the process.

Ongoing discovery plan post-depositions

We all know depositions as a means of getting real answers, important information, and locking Defendants into statements, opinions, and positions. Yet it is important that we don’t stop there. Post-deposition discovery is an important opportunity to dig deeper into topics discussed in depositions, obtain any documents that were identified, and confirm any admissions or contentions. Through depositions, the case evolves and begins to take shape with the new facts. Post-deposition discovery is key to keeping the pressure on and getting the information you need to prove your case.

It is best to do this while the information is fresh. Throughout the deposition it is a good idea to constantly be taking notes of the discovery you want to propound. As most of our depositions are conducted remotely, our office keeps a blank email open as a place to dump all new requests and interrogatories as they come up. When a deponent mentions a previously unidentified person or document, or makes an admission, we immediately take note. We have found that not only allows us to quickly get more information from the defense, but there are also times when a Defendant’s responses will directly contradict what their own witness just testified to. This is especially powerful when the defendant is a business, with multiple people answering discovery, and who love to provide evasive responses.

Locking in answers from businesses

Getting the necessary information in discovery from a corporate defendant can be frustrating. However, tailoring your post-deposition discovery based on how a deponent answers can lead to one of two responses: 1) the defendant will confirm or 2) the defendant will contradict the deponent. Either way, you have useful information that can be used at the time of trial.

An example of the first scenario comes from a premises case where lighting was a key issue. In the initial round of discovery, defendants would not admit or deny whether the light in question was out at the time of the incident. During deposition, the designated Person Most Qualified admitted that based on the photographs taken of the scene and the fact that other lights in the background were not on, that the light in question was indeed not on at the time of the incident. Following the deposition, we propounded both special interrogatories and request for admissions relating to whether the light in question was off at the time of the incident. Defendants’ responses confirmed the PMQ’s testimony, and thus a key issue was no longer in dispute.

An example of scenario number two comes from another premises case where there was a dispute as to whether an employee was certified to operate a piece of machinery in a big box hardware store. Many times, with a corporate defendant, the key defendant witnesses or Persons Most Qualified will work for a branch or location where the incident occurred. However, many times, the person aiding in discovery responses and signing verifications may be a person at a corporate headquarters in a different state.

During the deposition of the PMQ related to safety of the store, the deponent testified that the employee in question was not certified to operate the piece of machinery. The deponent in fact provided documentation that the employee in question did not even take the necessary training courses until two weeks after the incident occurred. Yet, when we sent the post-deposition discovery, the defendant definitively responded that the employee in question was “properly certified to operate” the piece of machinery on the date of the incident. Sure enough, the person who signed the verifications was upper management based in a corporate office in Atlanta, GA. Now, whatever defendant says during trial, we have a major contradiction on a key issue that the defendant will not be able to get around.

Getting specific

No matter how much you may know about your case when you file, the first round of discovery is meant to be probing and broad, so you can decide what depositions need to be taken and what further investigation needs to be done. As depositions are taken, you get a better understanding of the key players, the issues, and terminology the defendant uses. This knowledge allows your post-deposition discovery to be tailored, direct, and in their own language, making it harder for defense to provide evasive responses or object as “vague.”

Request for production

In a perfect world, when you ask for “any and all documents” in discovery, you would get “any and all documents.” However, we all know that is not the case. In depositions, we can learn of specific documents used by employees, standard operating procedures, or training requirements that may exist. By obtaining the name of these documents, where the documents are located, and the contents, you can propound targeted requests that make it more likely to get what you’re looking for. Further, by learning the terminology and systems of a company in depositions, you can propound discovery using their own language, making it difficult for a defendant to object as “vague and ambiguous.” For example, if you know that Home Depot’s internal system is called My Apron or U-Haul calls its training platform U-Haul University, it becomes harder for them to tell you they are confused about the documents you are asking for. Write down these specific terms to craft your post-deposition discovery.

Special interrogatories

Special interrogatories are a powerful tool after depositions because they can be used to focus in on or provide clarification on a deponent’s testimony. Many times, an employee will have been trained or taught a certain procedure but will not know the name of the training or process. Special interrogatories can be used to force the defendant to identify the document and describe a process that the deponent was referring to.

Refer to terms or phrases “as testified to by [deponent] in his/her deposition” in drafting your post-deposition discovery. For example, a manager for a major restaurant chain testified that she knew the procedure for viewing and retrieving surveillance footage after an injury in the restaurant. While she knew she learned these rules from a document, she couldn’t remember where it was written down. Post deposition we propounded several interrogatories targeted on the documents and procedures governing viewing and retaining surveillance footage, specific to her testimony.

Requests for admissions

As we discussed earlier, requests for admissions immediately after a deposition can either lock in an issue or catch defense in a lie. However, targeted requests for admission can also be used to find and whittle down the defendant’s position. This can be done by the request itself, but also through Form Interrogatory 17.1. If a deponent provides information that suggests that Defendant should admit a specific request, but the Defendant still wants to deny, they will have to provide facts, persons, and documents that support the denial. That information can lead to another person to depose or more documents to pursue.

It is also a good idea to use special interrogatories as another opportunity to obtain the same information by propounding special interrogatories that mirror both a request for admission and the subparts of Form Interrogatory 17.1. We will use a special interrogatory to ask a “yes or no” question, then followed by interrogatories requesting facts, documents, and persons with knowledge that support their response.

Using discovery at trial

Within 30 days of trial, take stock of the discovery responses you have amassed to date, and start figuring out which responses you might want to use at trial. Think about useful admissions and statements made by the defendant during written discovery: not just concessions on liability or damages, but the statements that really reflect the ridiculousness of the defense’s position. For example, maybe the defendant has doubled down on not knowing about the condition that caused your client to slip and fall, or maybe you got the defendant to admit that they have no video footage of the incident, despite the presence of cameras.

This was the case in a 2019 trial where the defendant mysteriously lost all information pertaining to employees working at the time of the incident as well as the footage of the incident itself. We prepared all of these written discovery responses to be used at trial in the testimony of the restaurant’s owner and manager, to really emphasize to the jury how disorganized and non-credible the defense was. While we did not have direct evidence that the restaurant created the spilled liquid that our client slipped in, we had substantial circumstantial evidence as well as inferences that could be taken against the defendant for failing to maintain this crucial information.

The Code of Civil Procedure allows you to read interrogatories at trial:

At the trial or any other hearing in the action, so far as admissible under the rules of evidence, the propounding party or any party other than the responding party may use any answer or part of an answer to an interrogatory only against the responding party. It is not ground for objection to the use of an answer to an interrogatory that the responding party is available to testify, has testified, or will testify at the trial or other hearing.

(Code Civ. Proc., § 2030.410.)

Similarly, section 2033.410 states that “any matter admitted in response to a request for admission is conclusively established against the party making the admission in the pending action, unless the Court has permitted withdrawal or amendment of that admission under Section 2033.300.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 2033.410, subd. (a).) Both of these code sections have been incorporated into the Judicial Council of California Civil Jury Instructions “CACI” Nos. 209 and 210. Make sure that these are included in your list of jury instructions to be read at trial.

Once you have your list of discovery ready, there are some additional steps you will need to take to ensure you can properly show the discovery at trial. You will want to make binders of the discovery to bring to trial, and you will also want to file a trial brief on the issue in the event you get a judge who is less familiar with these rules. The Los Angeles Superior Court rules for example, require that “[b]efore reading into evidence any portion of any deposition, interrogatory or request for admission. . . counsel must obtain leave of court and must then advise the court and opposing counsel which . . . numbers of the interrogatories or requests for admission are to be read.” (Los Angeles Superior Court Local Rule 3.158.)

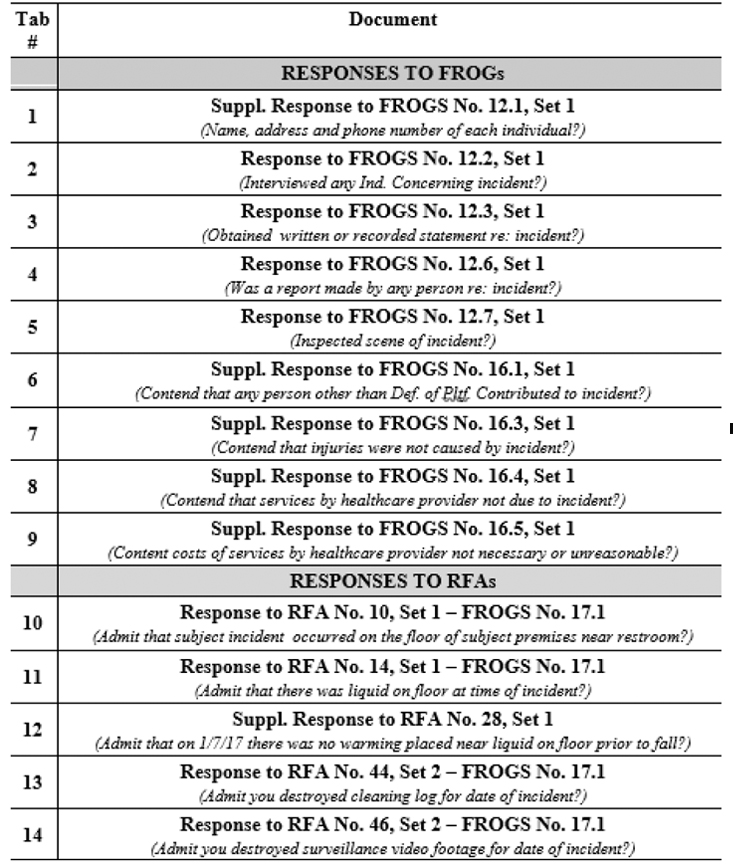

To set up your binder, re-type the question and response on a clean document with the objections removed. Behind that place the propounded request and the served response with the verification page. Create a table of contents that provides the reader with a brief summary of the question/response, such as the following:

Have these binders ready for the first day of trial and bring at least three copies (for yourself, the judge and the defense attorney). Even if you over-designate and do not use all of the discovery in trial, you will have at least prepared everything you might want to use, which is always better than the alternative.

Discovery can be effective during cross-examination and also just in the downtime of your case in chief. Consider how you strategically want to deploy the responses: Are you trying to set up a theme for the case? Then you might want to read the discovery into the record before a key witness takes the stand, or before you rest your case so that the issue is at the forefront of the jury’s mind before they hear from the witness. Are you leading a witness down the path of impeachment or to lock them into a certain position? In that instance, reading the discovery while they are on the stand will be very effective. Just make sure to advise the court ahead of time as to what you are doing so there are no disruptions while you are in session (especially if you go for the former option).

Conclusion

Written discovery is a great information-gathering tool, but it also has a really great impact when used at trial. By creating solid discovery plans early on, you can set up your slip and fall case for success all the way to verdict.

Teresa Johnson

Teresa Johnson is a trial attorney and partner at Kramer Trial Lawyers. She currently serves on the 2024 CAALA Board of Governors and as the co-vice chair of the Education Committee.

Brandon Salumbides

Brandon Salumbides is a trial attorney at Kramer Trial Lawyers A.P.C. in Century City. A graduate of Southwestern Law School, Brandon’s practice is focused in the area of personal injury.

Taylor Kruse

Taylor Kruse is a trial attorney at Kramer Trial Lawyers A.P.C. practicing personal injury and employment law on the plaintiff’s side.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine