Children with traumatic brain injury

Children’s brains are still developing, so TBI affects children far differently and more profoundly than adults

“Sometimes I look at my daughter when she is laughing and having fun and I wonder what she could have been had the incident never happened. When I see her beautiful face, sometimes I can’t help thinking she is not living the life she was born to live, and she is not the person she was meant to be.”— Ana P.

Daniela P. was so beautiful at birth that her mother, 20-year-old Ana P. could not wait to show her off to her relatives living in Los Angeles. Eleven days after giving birth to Daniela in Phoenix, she boarded a charter bus to Los Angeles with her precious baby girl. Although she brought an infant car seat with her, she was told that there were no seat belts on the bus to which it could be attached. As she settled into her seat with her baby snuggled in her arms, Ana had no idea that the entire trajectory of her daughter’s life would be forever changed on that bus.

At approximately 2:15 a.m., and while Ana was breastfeeding her daughter, the charter bus veered off the roadway near Blythe and rolled over in the dirt. The passengers on the bus, including 11-day-old Daniela, tumbled through the air like clothes in a dryer, striking different portions of the bus, each other, and flying debris before falling to the ground.

Amid all the dirt and dust and piercing screams in that dark bus, Ana noticed that her baby was quiet. As Daniela’s face turned purple, Ana knew that her baby had stopped breathing, and instantly started screaming for help. A fellow passenger grabbed Daniela and administered CPR until she began breathing and crying.

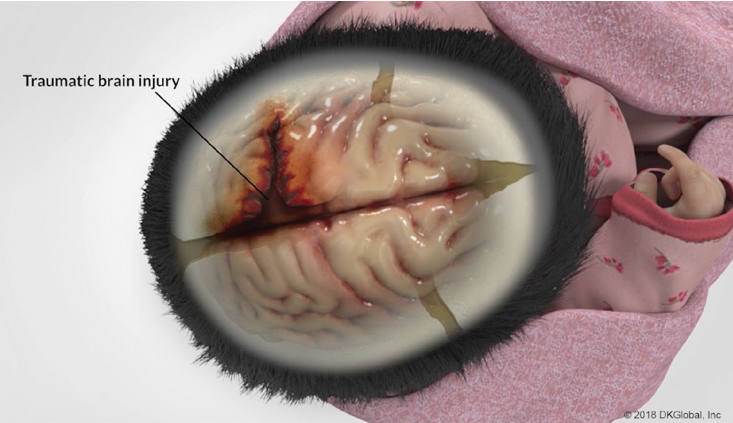

Although Daniela was initially seen and released by doctors at the hospital in Blythe, Ana instinctively knew that something was wrong with her baby. Daniela cried constantly whenever she was touched, and cringed as if she was in pain. And when she started projectile vomiting, Ana took her to the Phoenix Children’s Hospital. A CT scan revealed that Daniela had a displaced left parietal skull fracture with scalp swelling and hematoma, and doctors also diagnosed a fracture of her left arm. As Ana would soon learn, the long and difficult journey for her and Daniela had just begun.

Challenges in cases involving children with TBI

Although this case was unique in that it involved an infant who had sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI) when she was 11 days old, it highlights the many challenges and issues that will arise in any case involving a child with a TBI.

The statistics relating to children with TBI are staggering: A 2018 report to Congress on this issue revealed that among all age groups seen in emergency departments, it is young children that have one of the highest rates of TBI. (Report to Congress: The Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in Children, February 21, 2018.) Despite this fact, the report also indicated that “we know very little about the long-term adult outcomes of TBI in children.” (Ibid.) Growing research, however, has demonstrated that children with TBI will generally have academic difficulties, chronic behavior problems, social isolation, lower rates of employment, lower rates of post-secondary education, lower life satisfaction, social difficulties, difficulty in relationships, and higher rates of incarceration.

These serious adverse consequences of a TBI in an infant or child, therefore, require lawyers to consider a lifetime of needs and care. Unlike in cases involving adults, a lifecare plan for a baby or young child with a TBI could be for a period of 70 to 80 years. Because of the obvious costs associated with a lifetime of care, lawyers handling such cases must understand the various ways in which a TBI affects the child’s health and causes physical impairments, cognitive difficulties, and deficits in behavior/socialization.

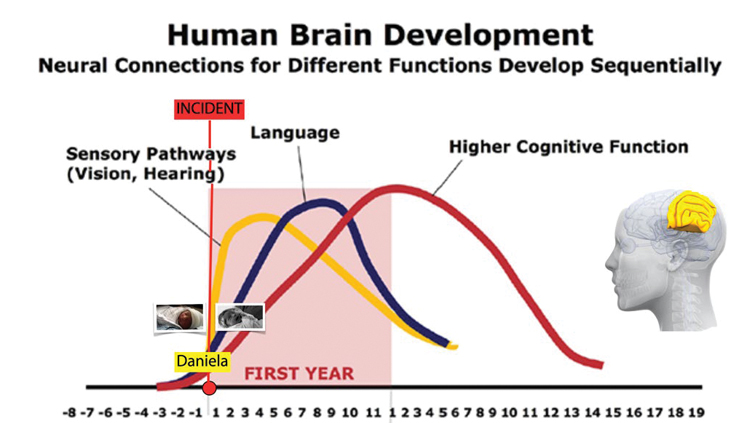

First, it is essential to recognize that a TBI affects children far differently and more profoundly than adults. The brain of a child continues to develop until reaching adulthood, and “an injury of any severity to the developing brain can disrupt a child’s developmental trajectory.” (Report to Congress: The Management of Traumatic Brain Injury in Children, February 21, 2018.) The brain’s ability to learn information is different for infants, children, adolescents, and adults.

Unfortunately for Daniela P, many of the critical learning periods occur during infancy and early childhood when the brain develops important pathways and connections in visual processing, sensory processing, motor processing, early adaptive skills, and language skills. If a brain injury occurs in the early phase of development, those pathways and connections are abruptly destroyed before anything can be learned – and deficits in those areas are inevitable. For this reason, medical experts agree that the earlier a child sustains a brain injury, the worse the outcome will be.

An adult with a TBI has learned all of these skills, and with therapy, his brain will find alternative ways to access such skills even with disruption in function. Daniela’s brain, on the other hand, never learned these important skills before her TBI occurred, and her pathways and connections were damaged before any learning could occur.

For these reasons, any jolt to the head of an infant or toddler should be taken seriously. The infant skull is very soft to enable the baby’s head to get through the birth canal, and as a result, the infant brain is extremely vulnerable to significant traumatic injury because even small impacts on such a soft skull can lead to considerable brain damage. Although the soft spot near the back of the head goes away by three months, the larger one on the crown takes approximately 18 months to close. The seams between the bones of the skull do not completely fuse together until the age of 20.

Ascertaining the full extent of a head injury in an infant or child presents its own unique set of challenges. Often, the baby, toddler, or child cannot communicate sufficiently, and many doctors and specialists will not administer certain tests that may indicate potential deficits until she reaches a certain age. Despite these realities, there are many sources of information available that should be explored.

Initial sources of information

The family is obviously the first source of a goldmine of information. In Daniela’s case, Ana immediately noticed differences between the growth and development of her baby in comparison to her son, who was a few years older. Both Ana and Daniela’s pediatrician noted significant developmental delays as Daniela grew. Getting the pediatrician’s records for Daniela’s wellness checkups and annual visits was important and useful. She did not meet the expected developmental milestones, including rolling over, sitting up, standing, walking, saying her first words, and exhibiting independence.

As a toddler, Daniela was often sleepy and getting her out of bed was difficult. She dozed while being showered, and fell asleep throughout the day. When she was awake, she was prone to having tantrums and crying fits. At the age of four, she had difficulty making friends or playing with other children. Ana was heartbroken when Daniela never received a single invitation to a birthday party. Daniela had difficulty remembering what she had learned. Even when repeatedly watching her favorite movie, Mulan, she never remembered the story or the characters.

As a single mother, Ana found it difficult to manage Daniela’s needs, which far exceeded those of her other children (including a newborn baby who was born after Daniela). The development of Daniela’s little sister far exceeded that of Daniela, and every milestone that was normally a cause of joy in a mother only served to re-emphasize Daniela’s deficits.

Without support and assistance, Ana was often overwhelmed. Daniela required the vast majority of her attention and care. Ana rarely left her side, and never felt comfortable leaving her in the care of a babysitter because she feared anyone else without an understanding of Daniela’s brain injury would lose patience with her.

Ana also noted that because Daniela is such a beautiful little girl, she often attracts a lot of attention from people when they are in public. Time after time, she saw their smiles turn into frowns after they realized Daniela was unable to respond to them in an expected manner. Ana constantly worries that because Daniela does not appear to be disabled in any way, she will be vulnerable to nefarious adults who will easily take advantage of her. Worrying about who will take care of Daniela is something that keeps Ana up at night, along with the guilt she feels for taking her baby on that charter bus on that fateful night.

School records provide invaluable information

Unlike adults, children attending school are assessed and measured on a daily basis by teachers and other educational specialists. Some of the most useful information in any TBI case involving a child will come from a teacher, especially if she knew the child before the TBI and can compare performances before and subsequent to the traumatic event.

Pictures drawn in class, noted behaviors, and school work during the school year provide important information. In addition, standardized tests are given to students annually, and recently, schools have instituted monthly i-Ready tests in math and English. Even before an attorney retains an expert, the chances are high that deficits have already been noted and recognized at school.

When the school finds deficits due to a traumatic brain injury, there are a host of services that can be made available to the student pursuant to federal and state laws. It is important that medical evidence of the TBI be provided to the school prior to requesting any support. Under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the school district must ensure equitable access to a learning environment. A student with a TBI who meets criteria for eligibility for a 504 plan can receive reasonable accommodations in school. Those who require more support and services are assessed by the school district in all areas of suspected disability to determine eligibility for special education, and an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is developed based upon assessment findings.

The IEP is not only individualized for the specific needs of a student with a TBI, but also enables teachers, parents, school administrators, related services personnel, and the student to work together to improve educational outcomes. Annual goals are developed and addressed, and the child’s progress toward her goals are measured regularly. The IEP is reviewed by the IEP team at least once a year, or more often if the parents or teachers ask for a review. Parents are given the opportunity to discuss their concerns. The child is thereafter reevaluated every three years to determine ongoing needs or continued eligibility.

It is important to note that students who attend private schools are entitled under the law to be assessed by their public school district to determine the need for a 504 plan or special education. While a 504 plan can be implemented in a private school, a parent will need to consider enrolling their child in the public school to receive special education services.

It is often surprising to learn the various services that school districts make available when presented with medical evidence of a brain injury. These may include access to specialists provided by the school district, including psychologists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists.

The power of these school assessments, 504 plans, and IEPs in a TBI case cannot be underestimated. The input of teachers and school districts’ specialists, who have no interest in the pending litigation, often has as much, if not more, impact than the reports of retained experts. Parents must be informed not only of this fact, but also of their important right to have considerable input by speaking up and relaying concerns at meetings.

How relevant are good grades?

Are good school grades fatal to a TBI case? Not at all. Depending on where the TBI occurred in the brain, and the age of the student, those with TBI may not initially be affected, and their grades will be similar to those they achieved prior to the TBI – particularly if they are bright students. Students with good grades, however, can exhibit other changes, such as withdrawal, depression, personality changes, poor social skills, poor learning behavior, disorganization, taking longer than usual to complete assignments/tests, depression, or use of drugs and/or alcohol. Years later, however, they could hit a wall academically with new learning or exhibit other difficulties. It is often not until the injured areas of the brain are tasked to process more complex information under increasing demands that the deficits may emerge. Unfortunately, in some cases, that can occur long after the case is over. With each year that passes, the brain-injured student will face new and different learning challenges, causing her to fall further behind her peers.

In special-education classes, in which many students with TBI are placed, grades given are often high because of the level of assistance and support provided to the student. Once that support is gone, however, many of those students will not sustain the good grades that provided a misleading picture of a high level of performance.

In many of my cases involving children with TBI, the grades were the least helpful measure of whether a student had a TBI. Some teachers admitted being “generous” to the student with a TBI because they felt sorry for her because of the traumatic incident. Other times, lower grades were more reflective of changes in behavior and work habits than a true measure of the student’s cognitive abilities. Grades, therefore, are but one of many measures that should be carefully assessed in these types of cases.

Experts to rely on in cases involving children with TBI

Although every case and every brain injury is different, the most helpful experts to explain the impact of the brain injury on the child’s functioning, and help your life care planner create a strong life care plan include:

Pediatric neurologist: What is going on in the brain after TBI?

Pediatric/developmental neuropsychologist: How does the TBI manifest in behaviors, development, and functioning?

Brain injury education specialist: What is going on and needed at school (which is like the child’s “work”)?

Obviously, these experts and treaters can refer you to other experts, such as a pediatric physiatrist or pediatric psychologist/psychiatrist if needed, but I find this core trio to be necessary in most cases. It is essential to find experts who specialize in pediatric patients. They must be experienced in working with babies, toddlers, children, and teenagers. Many times, they must get on the ground, crawl under a table, and play with the smaller children to gain their trust and to thoroughly assess them. Armed with toys, games, and shiny gold-star stickers, these experts know how to get the most valuable information from children with TBI in a non-threatening way.

The pediatric neurologist may choose to order tests. While most lawyers know the value of a CT scan, 3T MRI scan, or EEG test in a TBI case, the difficulty posed in cases involving children with TBI is that often, the accuracy of such tests depends on sedation to keep a squirming child from movements that could ruin the validity of such tests. Fast MRI, which provides an abbreviated and motion-tolerant sequence scan without sedation, is considered a reasonable alternative to a CT scan. When a routine EEG attempt has failed, sedation is sometimes required to allow for electrode application and a successful recording.

In Daniela’s case, an EEG performed when she was one year old demonstrated a global encephalopathy (brain dysfunction). Another EEG was performed a year and a half later, and also demonstrated a diffuse encephalopathic process. At the age of three, a 3T MRI was performed, and showed significant brain atrophy, decreased connectivity and cerebral volume loss on the left side of her brain in the area of the injury. The connecting fibers in the corpus callosum, which can be considered a “junction box” between the left and right sides of the brain, were unusually thin on the left side, and nerve fibers were gone in the left parietal lobe.

According to our pediatric neurologist, the MRI established that her brain injury and deficits are present, profound, and permanent. He also concluded that because these brain injuries occurred when she was an infant, certain deficits cannot be remedied by the of use ancillary measures (as can be done in older patients) because she never learned them, and her pathways of learning were destroyed.

Neuropsychological testing was also performed by a pediatric neuropsychologist when Daniela was three, and the results were remarkably consistent with what would be expected with her extensive brain injury pattern. Such testing included measures of functioning relating to intelligence, attention/executive functioning, memory, learning, language, and social, emotional, and adaptive skills. The results of such testing must be integrated with findings based on observational data, historical data, research data, and clinical experience.

Testing infants and toddlers

Although some defense experts maintain that infants and toddlers cannot be tested, and others refuse to test until a child is at least five years old, a skilled and experienced developmental pediatric neuropsychologist can and often does administer and interpret such tests to children under the age of five. For infants and toddlers up to the age of three, developmental and adaptive scales are used, such as the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development Screening Test. By the age of 2.5, intelligence can be measured by tests such as the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, Fourth Edition.

In Daniela’s case, our pediatric neuropsychologist found that Daniela’s IQ fell in the intellectually disabled range and her overall learning was in the first percentile range. There were deficits in all areas of development. She exhibited more aggression, anxiety, and withdrawal than a typical three-year-old, and she had problems performing simple activities of daily living. She concluded that Daniela’s developmental pathway was permanently altered, and that she would consequently always need support throughout the rest of her life. Because her basic brain functions have been altered, her trajectory will be quite different from that of her mother, brother, and sister.

A brain-injury education specialist, such as my co-author Sharon Grandinette, is vital to enable you and the jury to understand the full effects of the TBI on the student’s academic, social and behavioral functioning over time, and to guide both the parents and the school to identify areas of need and ways to access proper interventions and community supports that are often different from students with other types of disabilities. She works with families and schools to initiate the processes for a 504 plan, special education evaluation/services, and the IEP, and attends the IEP meetings to support the family and advocate for initial, continued or additional services. And often, families continue to use her after the case is resolved to monitor the student’s progress over time and ensure compliance with regard to the delivery of services.

When Ms. Grandinette arrived at Daniela’s house promptly at the agreed upon time at 9:00 a.m., she found that Daniela was still sound asleep and Ana had great difficulty waking her up. When she was finally awake hours later, she was unable to perform tasks that were done by other children her age. At the age of four, she could not trace over letters, and did not recognize letters or numbers. Her “artwork” consisted of a faint scribble. She did not know how to use child-safe scissors to cut around a square, and she could not draw a square on her own. She could not catch a bouncing ball, hop on one foot, or follow two-step directions. Instead of drawing a recognizable and age-appropriate stick figure, Daniela drew only squiggly circles. When asked, she could not find the picture of a boy on a bike.

Pre-school teachers told Ms. Grandinette that in class, Daniela could not retain information learned or apply information when needed. She would be able to name the parts of her body on one day and be unable to remember them on the next day. They also reported that Daniela had problems with socialization and aggressive behavior with toys and other children. Ms. Grandinette concluded that Daniela would require educational and therapeutic interventions at school, including speech and language therapies, behavioral interventions, occupational and physical therapy, tutoring, working memory therapy, assistive technology, and ongoing counseling.

Daniela was also evaluated during this time period by a multi-disciplinary team at her school. Not surprisingly, the team evaluation findings were similar to those of our experts, with deficits found with tasks requiring memory and long-term recall, daily living skills, socialization, and communication. She exhibited moderate delay in the cognitive domain, and her behavior assessment was significant for aggression and anxiety. The team determined that Daniela’s delay in cognitive development impaired her ability to learn new things or solve problems, and delays in her adaptive development impaired her ability to cope with her environment in an independent way, especially in the areas of dressing and toileting.

The school determined that Daniela was eligible for Special Education as a child with a disability and developmental delay due to a traumatic brain injury. An IEP was put in place and the IEP noted that Daniela would need adult supervision during physical activity to prevent another head injury, and confirmed that she presented with characteristics associated with TBI as manifested by cognitive difficulties and delays in mastery of age-appropriate adaptive behavior.

The life-care plan

Armed with this data, our experts worked together and concluded that Daniela would need intensive therapies and care for the rest of her life, and they made recommendations to our life-care planner. They believed that the degree of services she would require far exceeded what a single mother or the school district could provide.

Unfortunately, school district services in some rural areas have traveling therapists who are unable to provide the services as frequently as the student requires. And, if the district has a therapy vacancy, the law requires the district to fund a private therapist. At times, however, families have to travel for hours to obtain certain therapies or services. Our experts also agreed that as an adult, Daniela would require an advocate assistant on a full-time basis and a supervised living environment. None of our experts believed that Daniela would be able to hold a full-time job.

Our life-care plan addressed Daniela’s needs as a child and as an adult. During Daniela’s childhood, the plan provided for an advocate/case manager, assistance for Ana, intensive therapies, a TBI educational specialist, and counseling for Daniela and the family. The plan added a guardian once she reached adulthood, along with vocational assessment and training, and assisted living. Her advocate, therapies, and counseling will continue for the remainder of her life.

Depending on the recovery, it is important to remember to give a copy of the life-care plan after the case is resolved to the trustee or whoever is in charge of the funds. You may alternatively want to give a summary of the highlights of what your experts devised so that person has an idea what the child requires. In many instances, neither the parents nor the trustees know what the life care plan or experts contemplated regarding the use of the funds. It is a good idea to follow through by checking up with the family from time to time. Too often, the parents (or the trustee) are reluctant to spend any of the money because they want to save it for the child’s adult years. It is so important, however, for them to understand the importance of the use of some of those funds for those vital therapies and services that will help to improve their child’s functioning.

Other complicating factors to consider

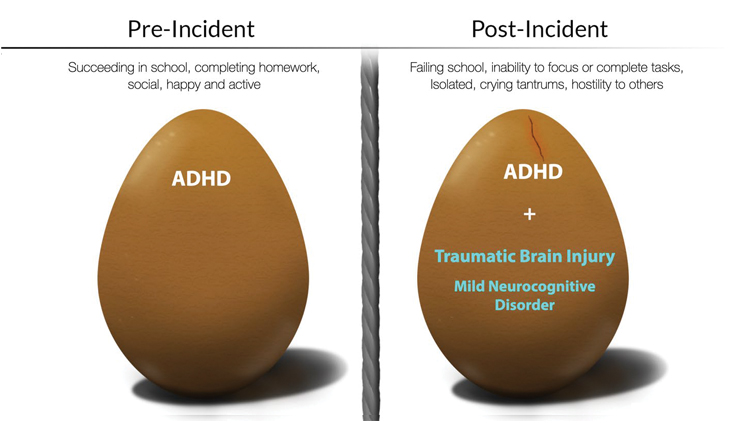

Whenever children are involved, many of the behaviors consistent with a TBI are also consistent with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and when there are diagnoses of both, your experts need to explain the significance of these diagnoses. In cases in which the child was diagnosed with ADHD before the TBI occurred, you must stress how much more difficult the ADHD becomes with the overlay of a TBI. Because the ADHD is made worse by the TBI, the defendant will be liable for damages resulting from the aggravation of the ADHD. (CACI 3927 Aggravation of Pre-Existing Injury or Condition.)

ADHD can also be diagnosed after the TBI injury. In fact, ADHD secondary to a TBI is one of the most common neurobehavioral consequences of a TBI, and occurs in 20-50% of patients. Research has demonstrated that if a child is less than two years old at the time of the TBI, her risk for the development of ADHD doubles when compared to the general population. Not surprisingly, Daniela was diagnosed with ADHD when she got older.

Non-economic damages in children with TBI cases

The past and future pain, mental suffering, loss of enjoyment of life, physical impairment, inconvenience, anxiety, humiliation, and emotional distress stemming from a TBI inflicted in childhood are so important to stress. Imagine being so different from your siblings and classmates, and not understanding why they all roll their eyes at you or make fun of you. Instead of living a satisfying and productive life, imagine being frustrated, anxious, and destined to suffer daily for the next 70 to 80 years.

On the day of the bus rollover, Daniela, at the age of 11 days, lost the enjoyment of a life she was supposed to have. She was left with a life full of frustration and anxiety and humiliation, as she is often unable to perform basic tasks or learn new ones. She reacts in the only way she knows how: by crying and throwing tantrums and tearing the heads off of her dolls. She falls asleep and sleeps excessively out of sheer exhaustion, as her body and brain struggle to compensate for her brain injury. And when she is awake, she overwhelms her mother, siblings, and teachers. She stands in contrast to her older brother and younger sister, who are generally considered the “easy” children. She has never had a friend, is never invited to a playdate or birthday party, and is often isolated and alone on the playground.

I once asked a pediatric neuropsychiatrist what it was like to live with a TBI as a child. He told me to imagine the next day as having the most important meeting of your life after pulling an all-nighter. You are so exhausted and tired, and you know what you want to say – but the words just don’t come to you because you are so tired. But they are right there on the tip of your tongue, and you become so frustrated trying to remember what you wanted to say. The stress and anxiety of trying to do a good job overwhelm you; your heart begins to pound and you begin to sweat. You become frustrated and angry because you cannot and do not succeed, but only you know how hard you tried. No one else appreciates your hard work, and instead they always focus on your failures. They get angry because you are too slow, too forgetful, and always running late.

It sounded to me like a nightmare. Yet that is also an apt description of what children with TBI go through, feel, and experience every day of their lives. For Daniela, every aspect of the rest of her life was adversely affected by her TBI. Her childhood should have been filled with joy and carefree days of fun; instead, she faces a lifetime of unimaginable suffering.

One of our most important jobs as attorneys is to be able to tell the stories of these children who cannot speak for themselves. The debt owed to these children is massive, and only you can make sure that debt is repaid.

Daniela P. today

Our case resolved by way of a settlement, and today the family lives in a house the trust purchased with some of the proceeds. Daniela is now 10 years old and in the fifth grade. She is in special education classes, and her IEP provides many therapies and services, which are supplemented with services paid for by her trust. Daniela’s teachers note improvements in her ability to retain information and follow instructions, and her tantrums have decreased. She is still beautiful and loves to wear a pretty dress. With the support and therapies that the settlement was able to provide, the entire family is thriving. Instead of worrying about Daniela all night, Ana now has hope for the future.

And with every passing day, her love and admiration for her brave daughter grows. Since she was resuscitated and began crying in that dust-filled dark bus as an infant, Daniela has never given up and never stopped fighting. Her progress may be slower than her siblings and other children in her school, but every achievement is celebrated. The trajectory of her life may have changed, but her settlement ensures that she will never have to face this alternate path alone.

Deborah S. Chang

Deborah S. Chang of Panish Shea & Boyle LLP is the recipient of the 2014 Consumer Attorneys of California (CAOC) Consumer Attorney of the Year Award. Deborah is a member of the Los Angeles chapter of the American Board of Trial Advocates (ABOTA), where she serves on the Executive Committee and is a National Board Member. She is also on the Executive Committee (2nd Vice President) of the CAOC.

Sharon Grandinette

Sharon Grandinette, M.S., Ed. CBIST, is an Acquired/Traumatic Brain Injury Education specialist, and is a Certified Brain Injury Specialist/Trainer who focuses her work on school reintegration for children with TBI. She has worked in public schools as a special educator and administrator for over 25 years, and is a former director of a children’s post-acute brain injury rehabilitation program.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine