Life-care planning for traumatic brain injuries

Obtaining just compensation for your client’s medical needs resulting from this most severe, life-changing injury

What is certain is that there is no certainty afforded to those who have suffered Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). Unlike an orthopedic injury, visualized through X-ray, or a soft-tissue injury, visualized through MRI, a traumatic brain injury is often one of the “invisible injuries” that are most difficult to convey in seriousness and substance to a jury. Quite simply, it is hard to make such injuries relatable to jurors with no familiarity or experience with those suffering lifelong sequala from a TBI. This being a truism, establishing the lifetime needs of one suffering a TBI is one of the most complex challenges for a trial lawyer, which requires great understanding, skill, and experience accompanied by a team of expensive, highly skilled consultants. The inclusion of a Physician Certified Life Care Planner (PCLCP), Certified Life Care Planner (CLCP), or Certified Nurse Life Care Planner (CNLCP) and a detailed life care plan (LCP) is essential to synthesize all of the medical testimony into a matrix the jury can rely upon in determining future economic damages required to provide a quality of life for your client.

What is a life-care plan?

For the uninitiated, according to the American Academy of Physician Life Care Planners, “a life care plan is a comprehensive document that objectively identifies the residual medical conditions and ongoing care requirements of ill/injured individuals, and it quantifies the costs of supplying these individuals with requisite, medically related goods and services throughout probable durations of care.”

For an LCP to be complete, the full extent of injury and disability must be documented long before the life-care planner becomes involved. This requires that the TBI sufferer understands the effects of a TBI, as many times, they go overlooked or are assumed to be because of medications being taken to treat other conditions or provide pain relief. Therefore, at the onset of a TBI case, a lawyer should refer the client and their family members to the National Institute of Health Neurological Disorders and Stroke TBI resource which can be found at https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi. This allows the client and their family members to understand and identify the myriad effects of a TBI so they can be related to healthcare providers and reasonable and appropriate diagnostics and care can be provided.

Signs and symptoms of a TBI are broken down into three major domains: physical symptoms, cognitive and behavioral changes, and perception and sensation changes. Physical symptoms include headache, convulsions or seizures, blurred or double vision, unequal eye-pupil size or dilation, clear fluids draining from the nose or ears, nausea and vomiting, slurred speech, weakness of arms, legs, or face, and loss of balance. Cognitive and behavioral symptoms include decreased level of consciousness (e.g., hard to awaken), confusion or disorientation, problems remembering, concentrating, or making decisions, changes in sleep patterns (e.g., sleeping more, difficulty falling or staying asleep, inability to wake), frustration and irritability. Changes in perception and sensation include light-headedness, dizziness, vertigo or loss of balance or coordination, blurred vision, hearing problems such as ringing in the ears, loss of sense of smell, unexplained bad taste in the mouth, sensitivity to light (including computer screens/cell phones) and sound, mood changes or swings, agitation, combativeness, or other unusual behavior, feeling anxious, depressed or suicidal, fatigue or drowsiness, and a lack of energy or motivation.

Because many TBI sufferers are not fully aware of the impact on their life, you should make sure that this information also gets into the hands of someone who knew them before the collision, such as a parent, spouse, or significant other, who has interacted with them since the injury. Most TBI patients are often unaware of the nature and severity of the changes they have experienced.

Given the broad constellation of injury identified in these three domains, a comprehensive LCP in a TBI case differs from a standard personal-injury LCP in that it must accommodate not only the medical care needs of the plaintiff but, also, cover areas of neurology, psycho-audiology, occupational psychiatry, pharmacology, cognitive rehabilitation, sleep therapy, ophthalmology, audiology, occupational therapy, financial management, home health assistance, and medical case management.

Qualifications for life-care planners

Three main bodies certify life-care planners: the American Academy of Physician Life Care Planners (Certified Physician Life Care Planner-CPLCP), the International Commission on Healthcare Certification (Certified Life Care Planners- CLCP), and the Universal Life Care Planner Certification Board (Certified Nurse Life Care Planner- CNLCP).

The requirements for a CLCP certificate include qualification as a healthcare provider with 120 hours of post-graduate or post-specialty degree training in life-care planning including modules in catastrophic-case management, vocational rehabilitation, and a legal component in life-care planning with onsite testimony/trial experience. The qualifications can be found at ichcc.org/certified-life-care-planner-clcp.html.

The requirements for physician certification as CPLCPs include an active license as an MD or DO, 10 years of clinical practice since residency, 10 years of board certification in at least one of the 24 medical specialties recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties, an active CLCP Certification from the International Commission on healthcare Certification, authorship of at least 25 life-care plans, and sworn testimony, in the role of a designated expert in the field of life-care planning, a minimum of 20 times. The qualifications can be found at cplcp.org/Certification.aspx.

The requirements for a CNLCP are: a current, unrestricted license in healthcare (or a health and human services discipline) that allows for independent patient/client assessment, for at least the prior two years immediately preceding application; a minimum of 4,000 hours paid or “billable” professional healthcare experience in a role that requires licensure and determination of Patient/Client needs within the five years immediately preceding application, and passing of the CHLCP™ Portfolio Examination.

In addition to the above certifications, there is a certification for a Brain Injury Specialist Life Care Planner offered by The Brain Injury Association of America’s Academy of Certified Brain Injury Specialists (ACBIS). Few life-care planners hold this certification; one who I worked with recently and was impressed by was April Stallings RN, BSN, CNLCP, CBIS. She was able to bring that extra level of expertise particular to brain injury that the defendant’s expert did not have.

Life-care plans are essential as TBI injuries present lifelong changes

Most people assume that all injuries get better or, at least, plateau. This is often not the case.

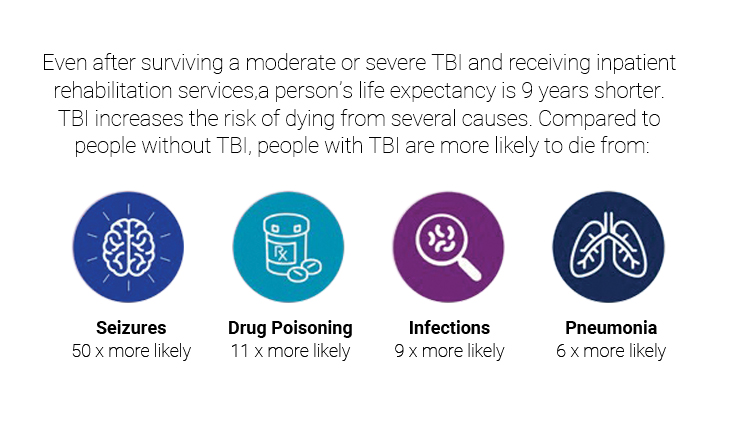

The outlook for individuals diagnosed with TBI, following initial hospitalization and subsequent inpatient rehabilitation is stark. Many peer-reviewed journals report that concussion and TBI increase the risk of progressive neurological degenerative conditions and a higher risk of the development of neurocognitive disorders such as dementia. (Neurology. (2000) 55:1158-66; J Neurol Neurosurg. Psychiatry. (2003) 74:857-62.)

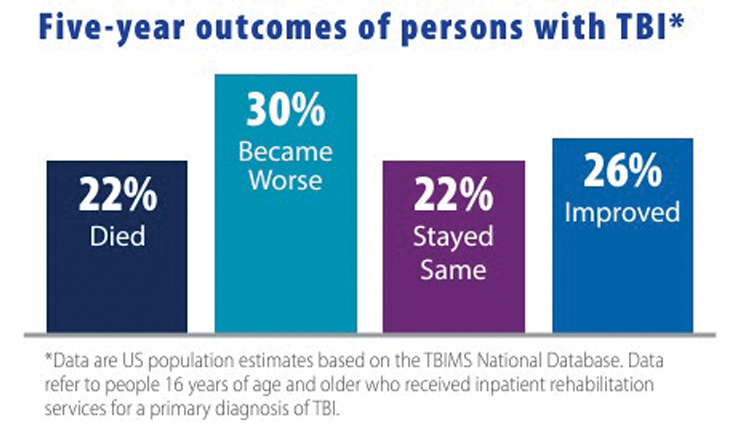

The Center for Disease Control has produced a publication entitled “Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury is a Lifelong Condition.” (www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pdf/moderate_to_severe_tbi_lifelong-a.pdf) This not only provides a useful guide in understanding the lifelong effects of TBI, but it can also be used as an exhibit in trial. The CDC paper contains useful charts including one showing five-year outcomes of persons with TBI who have received inpatient rehabilitation services reflecting that 74% stayed the same or got worse.

The same publication reports that there are well-documented long-term significant negative effects of TBI including a reduced life expectancy of nine years for those with moderate to severe TBI who have received inpatient rehabilitation services.

In addition, according to the same CDC publication, people with moderate to severe TBI typically face a variety of chronic health problems. These issues add costs and burdens to people with TBI, their families, and society. Among those still alive five years after injury: 57% are moderately or severely disabled; 55% do not have a job (but were employed at the time of their injury); 50% return to a hospital at least once; 33% rely on others for help with everyday activities; 29% are not satisfied with life; 29% use illicit drugs or misuse alcohol; and 12% reside in nursing homes or other institutions.

Providing this material to a CLCP can facilitate them to contextualize the moderate-to-severe TBI LCP.

Providing a comprehensive LCP

An LCP not only looks at future medical-care needs, but also presents the foundation for the jury’s consideration of the need for support and services. Therefore, your life-care planner must consider not only what medical care is reasonably certain in the future but, also, whether the injuries related to the TBI will necessitate the employment of individuals to manage a plaintiff’s affairs. In the most severe cases, this includes 24-hour in-patient care, which is easier to quantify and qualify. However, for most TBI cases the LCP is much more complex, involving many disciplines such as neurology, psychology, psychiatry, pain management, audiology, optometry, sleep disorders, speech therapy, occupational therapy, and cognitive rehabilitation.

Therefore, if your client has been made aware of the sequela of a TBI at the outset of their treatment and representation (as suggested earlier) they should have received reasonable and appropriate care for their applicable conditions and those treating physicians, or experts in those fields, can provide recommendations as to what care is reasonably certain to be required in the future. Generally, they provide a description of the type of service, good, medicine, monitoring, or treatment along with a frequency over the lifetime of the patient.

In addition to opining on the medical needs of your client, a life-care planner should analyze and prepare an opinion on what types of supportive services may be required to provide optimal living conditions. This often includes services for financial management, paying bills, shopping, assisting in the management of medical care needs (case management), and in-home assistance with personal care and home maintenance.

In many cases, by the time a case makes its way to trial, there has been some adaptation within the client’s familial or social circle to accommodate for the deficiencies presented by the TBI. A comprehensive life-care plan involves an in-person visit with the life-care planner and a home visit is a must. It is also imperative that the life-care planner speaks with close family members such as spouses, domestic partners, significant others, adult children, and/or roommates. They need to see the patient in situ, in their everyday environment, to see how they are living and what is needed by the patient.

They also need to talk to those most aware of the challenges and limitations facing the patient to determine not only how to help them cope, but what resources are required for them to live a safe, healthy, secure, and more complete life unhindered by their TBI.

In one of my cases, the life-care planner recommended a personal assistant for several hours twice a week after looking at the plethora of Post-it notes throughout the house and the degree to which their family member had to label all the drawers, bureaus, even post reminders above the washer-dryer to separate light and dark clothing before washing.

Following that same visit, childcare was recommended as the life-care planner learned that the plaintiff had forgotten to pick up his child after school on numerous occasions only to have the school call the mother, who was working full time to support the family. This created a safety issue for the child, a great deal of stress between the husband and wife, and a sense of shame for the plaintiff that he could not even care for his child. In some instances, daily assistance was deemed necessary when the lifecare planner learned that the plaintiff routinely forgot to take their medication and they presented a safety threat to themselves after forgetting that they had placed something on the stove and started a fire.

When speaking with a family member about post-TBI life, it is common to note caretaker burnout and a change in the relationship such as from husband and wife to patient and caretaker. Part of the design of a life-care plan is to provide support and services to permit a reformatting of the relationship to what it was before, thereby moving the burdens caused by the injury off of the spouse and onto professional service providers. Reestablishing these relationships should be one of the goals of a thorough life-care plan.

A life-care plan needs a proper foundation

CACI 3903A states, “To recover damages for future medical expenses, the plaintiff must prove the reasonable cost of reasonably necessary medical care that the plaintiff is reasonably certain to need in the future.” That’s a lot of reasonable language. For a medical need to be considered “reasonably certain,” it must be deemed reasonably necessary by a doctor. A life-care planner cannot, and should not, make a medical diagnosis or formulate a medical plan of care.

Therefore, you must make sure that the life-care planner has the foundation for future medical care by confirming that your client’s treating physician, or retained experts, have considered and formulated the requisite reasonably necessary treatment your client will require in the future and that they have disclosed them to the life-care planner. If you are in federal court, that same information must be detailed in the expert’s Rule 26 (a)(2)(B)(i) disclosure, which requires an expert to provide a complete statement of all opinions the witness will express and the basis and reasons for them. I have destroyed defense life-care planners who failed to speak with the defendant’s medical experts who have “winged it” based on recommendations given in other cases.

Remember, CACI 3903A speaks of both reasonable necessity and reasonable certainty. “It is not required” for a doctor to “testify that he [is] reasonably certain that the plaintiff would be disabled in the future. All that is required to establish future disability is that from all the evidence, including the expert testimony if there is any, it satisfactorily appears that such disability will occur with reasonable certainty. [Citations.]” (Paolini v. City & County of S.F. (1946) 72 Cal.App.2d 579, 591.)

Therefore, I suggest that you frame your questions to your client’s treating physicians and/or your retained experts in the following manner: “Doctor, do you have an opinion to a reasonable degree of medical probability what future care needs my client is reasonably certain to need in the future?” If the doctor answers yes, then have them provide a list. It may be preferable to break it out into categories, which are often used by life-care planners, such as future appointments with a neurologist, psychologist, psychiatrist, or other medical specialist; further diagnostic studies; medications; cognitive rehabilitation; durable medical equipment, etc.

Be sure to obtain the frequency that is germane to each type of care as some may be only one time, others for a limited period, and others beginning at a date in the future. Also, make sure your experts have formulated an opinion on how these needs may change as the plaintiff ages. Often the need for treatment and support and services increases with age. It is generally considered to be within the life-care planner’s ambit to opine what non-medical services will be reasonably certain in the future.

Get a life-care plan in report form, complete with tables and charts

The testimony of a CLP can be tedious for a jury; therefore, the use of a chart aids tremendously at trial. Establish that the chart is a summary of the expert’s analysis and opinion. Identify it and request permission to publish it as a demonstrative exhibit. Go through it in enough detail that you have established that the life-care planner, to a reasonable degree of probability, opines that each category is reasonable and necessary, and move the LCP into evidence. (Emery v. S. Cal. Gas Co. (1946) 72 Cal.App.2d 821, 824.) This provides the jury with an invaluable tool for evaluating damages later during deliberations.

Cross-examining the defendant’s life-care planner

Pursuant to Evidence Code section 721, a witness testifying as an expert may be cross-examined to the same extent as any other witness and, in addition, may be fully cross-examined as to (1) his or her qualifications, (2) the subject to which his or her expert testimony relates, and (3) the matter upon which his or her opinion is based and the reasons for his or her opinion.

The Law Revision Commission Comments are particularly instructive; “Under Section 721, a witness who testifies as an expert may, of course, be cross-examined to the same extent as any other witness. But, under subdivision (a) of Section 721, as under existing law, the expert witness is also subject to a somewhat broader cross-examination: ‘Once an expert offers his opinion, however, he exposes himself to the kind of inquiry which ordinarily would have no place in the cross-examination of a factual witness. The expert invites investigation into the extent of his knowledge, and the reasons for his opinion including facts and other matters upon which it is based and which he took into consideration; and he may be ‘subjected to the most rigid cross-examination’ concerning his qualifications, and his opinion and its sources [citation omitted].’ (Hope v. Arrowhead & Puritas Waters, Inc., 174 Cal.App.2d 222, 230, 344 P.2d 428, 433 (1959).”

When deposing a defense life-care planner, obtain their qualifications. See if they are a PCLCP, CLCP, or CNLCP. If they say they are, ask them if their certification is current. A certification has a “valid through” date. If they were never certified, ask them if they know what the qualifications are. The qualifications for PCLCP and CLCP and CNLCP are located at cplcp.org/Certification.aspx, ichcc.org/certified- life-care-planner-clcp.html, and ulcpcb.org/chlcp-certification/, respectively.

If they claim to have a PCLCP, CLCP, or CNLCP, verify their status. You can verify whether a physician life-care planner is certified at cplcp.org/Verification.aspx. You can verify CLCP certification at ichcc.org/clcp-listing-united- states-and-canada.html and a CNLCP certification can be verified at ulcpcb.org/verification/. If they are not certified, at trial ask them if they are certified; why they didn’t obtain a certification; why they didn’t tell the jury that they weren’t certified; do they know what the qualifications are for certification, and wouldn’t they agree that the opinion of a certified life-care planner has greater weight than theirs.

If they were certified at one point, and let their certification lapse, confront them with page 17 of Standards of Practice and Guidelines of the International Commission on Health Care Certifications (ichcc.org/images/PDFs/Standards_and_Guidelines_2023.pdf), which states that, “Failure to renew your certification will result in the revocation of your certified status.” Ask them why they didn’t tell the jury that their certification had been revoked. Get them to admit that ICHCC Rules of Professional Conduct R1.8, prohibits misrepresentation of their credentials. They will assuredly squirm (as will your expert if they are not certified).

As a PCLCP must have a CLCP from the ICHCC, a Physician Life Care Planner must also follow the Standards of Practice and Guidelines. The Standards and Guidelines state that, “The life care plan includes one-to-one, in-person contact with the injured or person with a disability.” Most defense life-care experts have not had one-on-one, in-person, contact with the plaintiff. They rely solely on what the defense medical experts say. Show them the Standards and Guidelines and have them agree that such a visit is required for a comprehensive LCP. Get them to admit that they did not follow the guidelines.

Since your life-care planner has had such an in-person visit, and hopefully an in-home visit, ask the defense life-care planner what they know about your client’s home environment, what coping skills she is using, what assistance she is receiving, etc. As most defense attorneys do not ask a plaintiff’s life-care planner what they observed and gleaned from their visit, the defense life-care planner will have no idea and the credibility of their opinion will be greatly undermined.

In the situation where the defense expert has testified there is no brain injury, or any injury was transient and fully resolved, there is no basis for the defense life care planner to provide testimony other than to do so based on accepting the plaintiff’s expert’s opinions. I have seen defense life-care planners offer, in essence, rebuttal testimony to challenge the plaintiff’s life-care plan.

Because a life-care plan is primarily based on the opinion of medical providers, the defense life-care planner should not be permitted to deviate from medical testimony by interjecting their own, contrary, non-medical opinions as to any future needs.

If it becomes apparent during their deposition that is what they are going to attempt to do, a motion in limine should be filed to exclude their testimony as they lack the expert qualifications required to opine as to future medical needs. If they are allowed to testify, get them to admit that their analysis is based upon the acceptance of the medical diagnosis and treatment plan offered by the plaintiff’s treating physicians.

Then their testimony is limited to proposing a different costing methodology for future medical needs and services and potentially challenging the need for non-medical support services such as in-home attendant care. If your life-care planner has used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for the prescribed treatment, in the relevant geographic area, the value of the services should not differ significantly in the defense life care “rebuttal plan.” If a defense life-care planner tries to use a “survey method” where they call physician’s offices and facilities to ask what a procedure or service costs, object as to hearsay as there is no way for you to cross-examine these out-of-court statements.

If the judge permits the testimony, during cross-examination, ask them how many providers within 100 miles provide these services, how many providers they called, and how many provided answers. The best I have seen is 15 calls with five providers providing information. This seriously undermines the survey-based opinion.

Conclusion

This article stems from decades of experience with life-care planners and will assist you in obtaining just compensation for your client’s medical needs so they may obtain optimal recovery from this most severe, life-changing, injury.

Christopher Dolan

Christopher Dolan is the founder of San Francisco’s Dolan Law Firm. Mr. Dolan, who is bilingual in English and Spanish, only represents individuals who have been injured, denied their rights, harassed, or wrongfully terminated. He was selected from among all of California’s lawyers as the Consumer Attorney of the Year for 2007. Mr. Dolan served as the 2010 President of the Consumer Attorneys of California, a board member of the San Francisco Trial Lawyers Association, and is a member of The Million Dollar Advocates Forum.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine