Elder-healthcare-facility arbitration agreements and the California Supreme Court

The California Supreme Court holds that signing an optional arbitration agreement is not a “healthcare decision”

Healthcare facilities increasingly rely on arbitration agreements to shield themselves from liability, effectively denying patients their constitutional right to a jury trial. By embedding these agreements within admission paperwork, facilities such as nursing homes often compel families to sign without fully understanding the implications. This practice allows the industry to leverage its position of power to avoid public scrutiny in the hindrance of transparency, mitigate legal consequences for abuse and neglect, and obstruct necessary reforms to protect vulnerable patients.

Signing an arbitration agreement is fundamentally a legal and procedural matter, not a healthcare decision. It pertains to how disputes will be resolved rather than directly impacting the care and treatment a person receives. These agreements primarily limit the legal rights of patients and their families rather than ensuring better health outcomes or quality of care. Consequently, presenting arbitration agreements as part of the admission process conflates legal obligations with healthcare decisions, misleading families during a critical and often stressful time.

In Harrod v. Country Oaks Partners, LLC (2024) 15 Cal.5th 939 (“Harrod”), the Supreme Court considered whether a “healthcare” agent, who had signed two contracts with a skilled-nursing facility on behalf of a principal, had the authority to sign an optional, separate arbitration agreement. The Court concluded that executing the arbitration contract was not a “healthcare decision” within the healthcare agent’s authority. This article will examine the Harrod case and its future implications, along with previous court decisions regarding the authority of a healthcare agent in the context of signing an arbitration agreement.

Historical legal authority on arbitration agreements as healthcare decisions

The California Supreme Court previously examined whether a patient was bound to an arbitration agreement in a group-negotiated health plan in Madden v. Kaiser Foundation Hospitals (1976) 17 Cal.3d 699. Finding arbitration was a “proper or usual” part of the agent’s powers to select a grievance procedure, the Court concluded that the representative who contracted for medical services on behalf of the patient had implied authority. (Id. at pp. 705-709, citing Civ. Code, § 2319.)

Two Court of Appeal decisions relied on Madden to conclude that agents designated in healthcare powers of attorney (typically included in Advance Health Care Directives) similarly possess the authority to bind their principals to pre-dispute arbitration agreements. (Garrison v. Superior Court (2005) 132 Cal.App.4th 253, 267; Hogan v. Country Villa Health Services (2007) 148 Cal.App.4th 259, 267.)

The Garrison court focused on the fact that the arbitration agreement was included in the nursing-home admission package, making arbitration “part of the admissions process.” The court found that, since the decision to enter a nursing home is considered a healthcare decision, agreeing to arbitration was a “necessary or proper” part of a healthcare agent’s authority. Hogan reached the same conclusion, noting that the California legislature contemplated that arbitration agreements were part of the admissions process. (Hogan, supra, 148 Cal.App.4th at p. 265, citing Health & Saf. Code, § 1599.81.)

Since Garrison and Hogan, a few California cases have addressed the authority of a power of attorney agent to bind principals to arbitration agreements. In Young v. Horizon West, Inc. (2013) 220 Cal.App.4th 1122, 1129, the court, in dicta, disagreed with Garrison’s “broad” conclusion that healthcare decisions include executing arbitration agreements. In contrast, another court concluded that an agent authorized to make healthcare decisions bound a resident to an arbitration clause within a Residential Care Facility for the Elderly admission agreement. (Hutcheson v. Eskaton Fountainwood Lodge (2017) 17 Cal.App.5th 937,945-958.)

In Harrod, the California Supreme Court disapproved of Garrison and Hogan, holding that signing an optional, stand-alone arbitration agreement is not a healthcare decision.

Harrod background

Charles Logan had fallen at 76 years of age, breaking his hip, and became unable to walk. He entered Country Oaks Care Center, a skilled nursing facility, to obtain living assistance and rehabilitative care. Upon admission, his nephew, Mark Harrod, signed two agreements with the nursing home on his behalf: (1) a state-mandated admission agreement that entitled Mr. Logan to care at the facility and (2) a stand-alone, optional arbitration agreement that was not required for admission or to receive care. Both state and federal law prohibit nursing homes from requiring arbitration agreements to be signed as a condition for admission. (Health & Saf. Code, § 1599.81, subds. (a), (b); 42 CFR § 483.70(n) (2019).) Mr. Logan previously designated his nephew as his “healthcare agent” to make “healthcare decisions” under a power of attorney for healthcare.

During his stay at Country Oaks Care Center, Mr. Logan suffered a second fall, was unnecessarily diapered, and developed pressure sores. He filed an action for elder abuse and neglect, negligence, and violations of residents’ rights. The nursing home defendants moved to compel arbitration. The trial court denied the motion, reasoning that the healthcare power of attorney did not authorize Mr. Harrod to enter into a stand-alone arbitration agreement on behalf of Mr. Logan. The California Supreme Court unanimously agreed.

Harrod analysis

In concluding that an agent holding a healthcare power of attorney does not have the authority to submit claims to binding arbitration, the California Supreme Court distinguished its 1976 decision in Madden, 17 Cal.3d 699, by noting that the group health plan was negotiated by an agent who had express power to negotiate contracts that included the selection of a grievance procedure. (Harrod, 15 Cal.5th at p. 961-962.) In contrast, the healthcare power of attorney did not mention the power to select a dispute resolution method – it merely granted the authority to make “healthcare decisions.” Because the arbitration agreement was a side agreement that had no impact on future care, the arbitration agreement did not affect a healthcare decision. (Id. at p. 962.)

The Court could have relied on this common-sense analysis and ended there. A pre-dispute arbitration agreement cannot be necessary for making a healthcare decision if offered as an option. However, the decision reaches beyond this approach in good and bad ways.

The decision begins with an analysis of California’s Health Care Decisions Law (CHCDL) (Prob. Code, § 4600 et seq.), which governed the healthcare power of attorney instrument signed by Mr. Logan. Under these provisions, a healthcare agent was authorized to make a “healthcare decision,” defined as a decision regarding the patient’s “care, treatment, service, or procedure to maintain, diagnose, or otherwise affect a patient’s physical or mental condition.” (Prob. Code, § 4615, 4617.)

A healthcare decision includes the selection and discharge of healthcare providers and institutions. (Prob. Code, § 4617, subd. (a).) Applying established canons of statutory construction, our Supreme Court concluded that the CHCDL directly pertains to who administers health care and what may be done to a principal’s body in health, sickness, or death. “There is no catchall provision, no express delegation of power . . . to waive access to the courts, agree to arbitration, or to otherwise negotiate about or accept any dispute resolution method.” (Harrod, supra, 15 Cal.5th at p. 1145.)

The decision next reviews the legislative purpose of the CHCDL, which was to ensure a patient’s fundamental right to control personal and private healthcare decisions, especially at the end of life. (Id. at pp. 1145-1146.) Neither the Legislature nor a patient appointing a healthcare agent would have viewed an optional arbitration agreement as a healthcare decision under this context.

When designating a healthcare agent or making advance healthcare directives, a patient must necessarily reflect on what should happen in the unfortunate event of severe illness or death, such as whether they want life-sustaining treatment like a feeding tube or to become ventilator-dependent. A pre-dispute arbitration agreement likely does not cross one’s mind during this critical reflective process. This analysis was good as our high court finally considered the circumstances unique to patients in determining whether an arbitration agreement is enforceable.

Future implications

Here is the bad. The analysis hinges entirely on the applicability of the CHCDL. It is problematic because patients may, but need not, use the statutory form to create advance healthcare directives outlined in Probate Code section 4701. (Prob. Code, § 4700.) While anyone can find and fill out the statutory form, many others utilize forms advanced by the healthcare industry. In fact, the California Medical Association drafted the form that Mr. Logan used, and the organization unsurprisingly appeared as amicus curiae to advise that healthcare decisions include an optional arbitration agreement. Our high court noted that the CHCDL “govern[s] the effect” of the writing, regardless of the form used, citing Probate Code section 4700. However, the healthcare industry is now guaranteed to manipulate its drafted form to include a broader reference to arbitration.

Additionally, the decision explains the differences between the CHCDL and the Uniform Statutory Form Power of Attorney Act. The latter provides a statutory form for durable financial powers of attorney, which commonly includes the power over “claims and litigation.” (Prob. Code, § 4401.) The rationale is that a healthcare power of attorney and a financial power of attorney are mutually exclusive, such that an agent holding the financial power of attorney has the authority to enter binding arbitration, but the healthcare agent does not.

The decision likely includes this analysis as a defensive mechanism because the Federal Arbitration Act preempts any “clear-statement rule” that a power of attorney instrument must expressly reference the waiver of a constitutional right to a jury trial and arbitration. (Kindred Nursing Centers, L.P. v. Clark (2017) 581 US 246, 250.) Our high court specifically noted that their decision “does not emerge from or reflect hostility to arbitration” since a principal or any “properly authorized agent” may agree to arbitration. (Harrod, supra, 15 Cal.5th at p. 1155, citing Madden, supra, 17 Cal.3d at p. 706.)

Ensuring that a principal knowingly authorizes an agent to commit to binding arbitration should never be viewed as hostility toward it. In defensively posturing that financial powers of attorney may still bind principals to arbitration, our high court failed to apply the same thoughtful consideration of the difficult choices patients and families must make, especially in a healthcare setting. The California Supreme Court gave much weight to the fact that neither the statutory healthcare power of attorney nor Mr. Logan’s form suggested that an appointed healthcare agent is authorized to make decisions concerning dispute resolution. (Id. at p. 1145.) However, California’s statutory financial power of attorney also does not alert the principal that they are authorizing the waiver of a constitutional right to a jury trial.

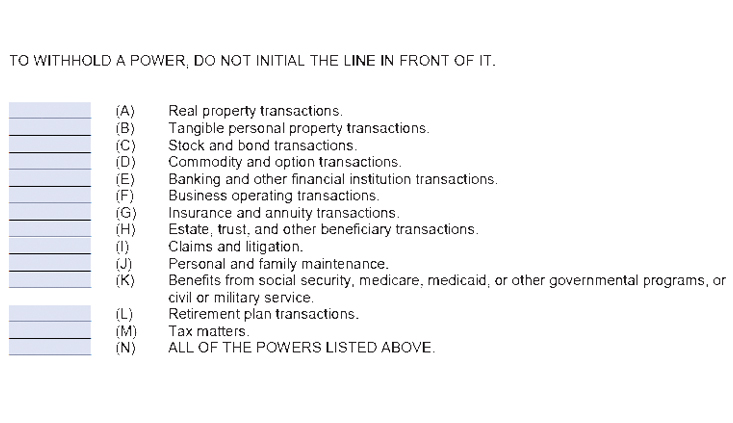

The form merely asks the principal to initial enumerated powers, including “claims and litigation”:

Although “claims and litigation” is statutorily defined to include the power to “submit to arbitration,” (Prob. Code, § 4450, subd, (d)), arbitration or a jury trial waiver is not mentioned on the form. Financial powers of attorney are often utilized simultaneously as healthcare powers of attorney. The same rationale should apply in upholding the principal’s intent in signing the form and ensuring that an agent does not “go beyond it or beside it.” (Harrod, supra,15 Cal.5th at p. 1144.)

A party cannot be compelled to arbitrate a dispute that he [or she] has not agreed to resolve by arbitration. (Goldman v. SunBridge Healthcare, LLC (2013) 220 Cal.App.4th 1160, 1178.) “Arbitration . . . is a matter of consent, not coercion. . . .” (Id., citing Volt Info. Sciences, Inc. v. Bd. Of Trustees (1989) 483 US 468, 479; see also, Morgan v. Sundance (2022) 142 S.Ct. 1708, 1713 [“The federal policy is about treating arbitration contracts like all others, not about fostering arbitration.”].)

Conclusion

Healthcare decisions are deeply personal to a person, and families are often forced to make these difficult decisions in times of sickness and failing health. Their thoughts are hope for recovery or peace at the end of life. Far from their minds are whether they should submit to binding arbitration if they are ever mistreated, neglected, or abused by care providers. Harrod appropriately considered these circumstances and applied common sense analysis to conclude that a healthcare agent did not have the authority to sign an optional arbitration agreement.

Art Gharibian

Art Gharibian founded Gharibian Law, APC, a boutique civil litigation firm whose practice focuses on elder-abuse/neglect and wrongful-death cases against nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Email: art@gharibianlaw.com.

Amber Tham

Attorney Amber Tham joined Gharibian Law, APC, as a senior attorney in 2021, bringing over 10 years of experience obtaining justice and advocacy for elder abuse and neglect victims. amber@gharibianlaw.com.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine