Arguing punitive damages

You are now arguing on behalf of society to not only punish the bad conduct but to prevent it from happening again

Trying cases is kind of like being in a boxing match. You’re fighting every day and whether you think it’s going well or not, you just don’t know if you’re ahead or behind on the jury’s scoring card. That’s why, like a boxer, no matter if you’ve had a good or bad day in trial, you shake it off and go in the next day to fight again. But all that changes when the jury has made a finding of malice, oppression or fraud and you find yourself now in phase II of a bifurcated trial seeking punitive damages.

In my experience, when you get to the second phase, you have to remember that the jury is on your side and has found, by clear and convincing evidence, that the defendant’s conduct was “despicable.” So, your demeanor needs to be like that of a heavyweight champion who is being interviewed after defending the title. You no longer need to be the aggressive fighter who is zealously arguing every issue. The jury has already found that the conduct is really bad, and now it’s the time to calmly reason with the jury about what to do about it. I remind the jury that we are doing this collectively, on behalf of society, to make sure this bad conduct is both punished, and more importantly, deterred and not repeated.

The punitive phase opening statement

Phase II is really a mini trial. Accordingly, I always give a short opening statement before the beginning of the second phase. I start by explaining the purpose of this phase with something like this:

“Ladies and gentlemen, we have now completed phase I of this case with your verdict. As I stated, the purpose of the first phase was to compensate my client, and you’ve now done that. But now we leave my client and the focus is 100% on the defendant and its conduct. The purpose of this second, and most important, phase is to determine what we as a society are going to do about punishing this conduct and making sure that it doesn’t happen again. And this is a very, very serious and solemn proceeding. You have found the conduct of this company to amount to malice, oppression and fraud by clear and convincing evidence. That is the highest form of misconduct you can find in a civil case like this, so, as you can imagine, this is a very serious proceeding to determine the appropriate punishment for this conduct.”

I will tell the jury that the only new evidence that they will hear is the financial condition of the defendant. I usually explain that the second phase is so sacred that we are not even allowed to talk about how much money the defendant has during phase I because we don’t want it in any way to influence their decision about whether the conduct itself was malicious, oppressive or fraudulent. Simply put, we wanted a pristine and objective finding from them about the conduct, which we now have with their first phase verdict.

I usually finish the brief opening by letting the jury know that after they get the evidence of the worth of the defendant, there will be closing arguments at which time I will be recommending an amount they should award to accomplish the purpose of punishment and deterrence.

Evidence of financial condition

The only new evidence to present during the punitive-damage phase is of the company’s financial condition. If the case is against an insurance company, getting the company’s financial information is very simple because they are required to file that information with the Department of Insurance, which then publishes it online. But in some instances, the financial condition of the defendant is not publicly available, and you may not be able to obtain discovery on it until you reach a second phase, unless the court otherwise finds good cause. In those circumstances, you must be prepared to comply with Civil Code section 3295, subdivision (c), which states, in relevant part:

No pretrial discovery by the plaintiff shall be permitted with respect to the evidence referred to in paragraphs (1) and (2) of subdivision (a) unless the court enters an order permitting such discovery pursuant to this subdivision. However, the plaintiff may subpoena documents or witnesses to be available at the trial for the purpose of establishing the profits or financial condition referred to in subdivision (a), and the defendant may be required to identify documents in the defendant’s possession which are relevant and admissible for that purpose and the witnesses employed by or related to the defendant who would be most competent to testify to those facts…

(Emphasis added).

Usually, I have retained a forensic economist to explain to the jury what the numbers in the financial documents mean. There are many ways to evaluate the financial condition of the defendant. For example, in the case of an insurance company, the most common way is to look at the company’s surplus, but in other instances it could be the company’s profits. Regardless, a forensic economist can help explain what the numbers mean to the jury. Once the financial condition evidence is presented, it is time for the final closing argument.

The phase II closing

While you know that the jury thinks the company’s conduct was really bad, you don’t know what they are willing to do about it. It’s your job as the trial lawyer to motivate the jury to “send a message,” not just to the defendant in your case, but also to the industry at issue. The starting point is to make sure to explain the purpose of punitive damages which is twofold: to punish and deter. Cite to the jury instruction as follows:

The purposes of punitive damages are to punish a wrongdoer for the conduct that harmed the plaintiff and to discourage similar conduct in the future.

(CACI 3949) (Emphasis added)

It is important that the jury understand that punitive damages are designed to protect the public, which includes the members of the jury. One way to accomplish this task is to refer the jury back to the law. For example, in California, one powerful jury instruction is the following:

The purpose of punitive damages is purely a public one. The public’s goal is to punish wrongdoing, and thereby protect itself from future misconduct, either by the same defendant or other potential wrongdoers. In determining the amount of punitive damages to be awarded, you are not to give any consideration as to how the punitive damages will be distributed.

(Adams v. Murakami (1991) 54 Cal.3d 105, 110; Neal v. Farmers Ins. Group (1978) 21 Cal.3d 910, 928, fn 13) (emphasis added).

Thus, in the punitive phase, portray your role as being one of a public servant. You are advancing the “public’s goal” which is, in part, to punish the defendant’s conduct and deter future misconduct. Ultimately, the jury should understand that their punitive verdict will protect not just an individual or some special interest group, but rather, will protect everyone from future abuses. The jury must understand the importance of their role of protecting the public in the punitive phase.

It is important that the jury understand that they have the power to send a warning to the industry at issue that misconduct will not be tolerated by the public. The jury can do this by making an example of the defendant. Again, one way to accomplish this is to refer to the jury instructions, such as the following from the United States Supreme Court:

In addition to actual or compensatory damages which you have already awarded, the law authorizes the jury to make an award of punitive damages in order to punish the wrongdoer for its misconduct or to serve as an example or warning to others not to engage in such conduct.

(TXO Production Corp. v. Alliance Resources Corp. (1993) 509 U.S. 443, 459, 463) (emphasis added).

A message to the industry

The punitive damages that the jury awards will not only send a message to the defendant about how it should do business in the future, but it will also serve as an example or a warning to other competing companies that the public will not tolerate such misconduct. Give the jury examples of warnings they see every day: If a swimming pool is too shallow, it should have a warning; if a product is dangerous, it should have a warning; if a floor is slippery, it should have a warning, etc. Warnings like these must be prominently displayed to have an impact. Explain to the jury that for their punitive damage award to serve as a warning to other companies it must be a meaningful amount to be prominently displayed to the industry.

I like to emphasize the second purpose of punitive damages, which is deterrence. The jury’s verdict should not only deter future wrongdoing by the defendant, but also by the industry. Another effective jury instruction to establish this point is the following:

The object of [punitive] damages is to deter the defendant and others from committing like offenses in the future. Therefore, the law recognizes that to in fact deter such conduct, may require a larger fine upon one of larger means than it would upon one of ordinary means under the same or similar circumstances.

(TXO Production Corp. v. Alliance Resources Corp. (1993) 509 U.S. 443, 459, 463, 113 S.Ct. 2711, 2721-2722, 125 L.Ed.2d 366) (emphasis added).

Once the jury understands the “purely public” purpose of punitive damages, it is then time to turn to the amount of punitive damages to assess. The guidelines for the assessment of punitive damages include the following:

1.) How reprehensible was the conduct?

2.) Is there a reasonable relationship between the amount of punitive damages and the harm?

3.) In view of the financial condition of the defendant, what amount is necessary to punish and discourage future wrongful conduct? (See, CACI 3949.)

Naturally, the evidence under each of these guidelines will largely depend on the facts of a given case as to the reprehensibility of the conduct, the defendant’s financial condition, and the plaintiff’s actual injury. These facts must be presented in evidence and then argued specifically to the jury. In addition to these general guidelines, there are other authorities that speak more specifically to the amount of punitive damages. Take the following special jury instruction:

In determining the amount of punitive damages to be assessed against a defendant, you may consider the following factors: One factor is the particular nature of the defendant’s conduct. Different acts may be of varying degrees of reprehensibility, and the more reprehensible the act, the greater the appropriate punishment. Another factor to be considered is the wealth of the defendant. The function of deterrence and punishment will have little effect if the wealth of the defendant allows it to absorb the award with little or no discomfort.

(Neal v. Farmers Ins. Exchange (1978) 21 Cal.3d 910, 928) (emphasis added).

These jury instructions convey credibility to your argument on the amount of punitive damages the jury should award. In other words, the jury should be told that the law requires a greater punitive damage award where the conduct is particularly reprehensible, and that the law requires that the amount the jury awards in punitive damages must cause some financial “discomfort” to serve the public purpose of deterrence as discussed earlier. Naturally, determining what amount will cause the appropriate “discomfort” will depend on the financial condition of the defendant. This concept is further set forth in another special jury instruction:

The wealthier the wrongdoing defendant, the larger the award of punitive damages needs to be in order to accomplish the objectives of punishment and deterrence of such conduct in the future.

(Adams v. Murakami, (1991) 54 Cal.3d 105, 110) (emphasis added).

This concept of discomfort is part of what we, as a society, associate with punishment in the criminal setting. I will usually have a slide with a picture like the one at the beginning of this article: a prison cell on one side, and a luxury hotel suite on the other side.

The point to make to the jury is that if the sentence for a crime is that, instead of going to prison a person would be sent to live in a luxury hotel suite, there would be no punishment or deterrence.

Similarly, if the punitive damage award in the civil setting is not significant enough to be meaningful and cause discomfort to the defendant, then the objective of punitive damages of punishment or deterrence is also not met.

Another analogy that is helpful in arguing punitive damages is the diamond lane violation. I will usually have a slide of a diamond lane highway (Figure 1 on previous page).

The analogy would be that if a person were stuck in traffic on the freeway and late for an important meeting, and they see a car driving by at full speed in the diamond lane, the thought is to jump in the diamond lane to get to the meeting on time. But the person decides not to do so when the carpool lane sign warns that the fine for a diamond lane violation is $490 and that driving over the double yellow line to get into the diamond lane is a moving violation, which will be reflected on the driving record, which will cause insurance rates to increase. In that setting, the potential punishment provided the deterrent effect to prevent the violation.

On the other hand, if the penalty for a diamond lane violation were only $5 and would not be reflected on the driving record and not adversely affect insurance rates, the driver would gladly commit the diamond-lane violation, even knowing that it is wrong, because the potential punishment does not have a deterrent effect. This demonstrates why the punitive damage award must be meaningful to the defendant to deter further misconduct.

When asking for an amount of punitive damages, I like to remind the jury that the corporate defendant must be treated the “same” as an individual in the eyes of the law. I refer to the following instruction:

A corporation, ABC Company, is a party in this lawsuit. ABC Company is entitled to the same fair and impartial treatment that you would give to an individual. You must decide this case with the same fairness that you would use if you were deciding the case between individuals.

(CACI 104) (Emphasis added).

When arguing this instruction, I tell the jury that we all know what it means to treat the defendant the “same.” We don’t treat them any worse, but we don’t treat them any better either.

I ask the jury to consider that if instead of a company that cheated my client out of money it was an individual who had a net worth of $100,000 what would they say? Well, it comes down to three things. First, we would say, “give the money back.” I remind the jury that the purpose of phase I was just that; to give the money back to my client. The second thing we would say to that individual is, “You’re going to jail.” Why? Because people who cheat other people out of money go to jail. It’s called a white-collar crime. I tell the jury that we can’t put a corporation in jail so, at least to that extent, we really can’t treat them the same as an individual. The third and final thing we would say is that the individual must be punished with a penalty to make sure the misconduct is not repeated.

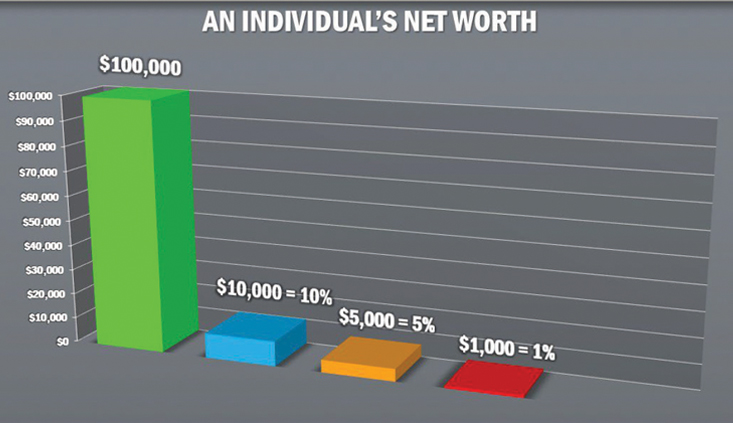

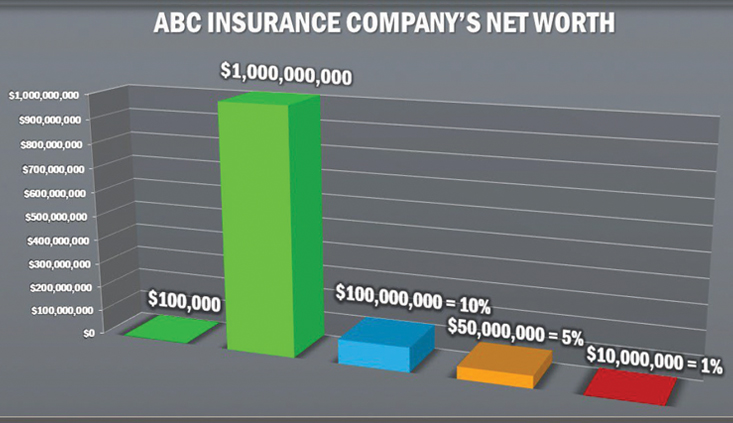

I explain that to an individual with a net worth of $100,000, a minor penalty of $10,000 or $5,000 amounts to 10% or 5% of that person’s net worth. Yet, that same 10% or 5% to a corporation that has a net worth/surplus of $1 billion, equates to $100 million or $50 million. But, equating what a reasonable punishment would be to an individual, to what it would be to the company, is treating the company the “same” as an individual. No better and no worse.

This concept can be visualized with demonstrative graphics (figures 2 and 3 on page 48). The graphics illustrate that while the punitive damages against a large corporation may be a large dollar amount, they are not so large when seen as a percentage of what that corporation is worth.

Ricardo Echeverria

Ricardo Echeverria is a trial attorney with Shernoff Bidart Echeverria LLP, where he handles both insurance bad-faith and catastrophic personal-injury cases. Hewas named the 2010 CAALA Trial Lawyer of the Year, the 2011 Jennifer Brooks Lawyer of the Year by the Western San Bernardino County Bar Association, and a 2012 Outstanding Trial Lawyer by the Consumer Attorneys of San Diego. He was also a finalist for the CAOC Consumer Attorney of the Year Award in both 2007 and 2009, and is also a member of ABOTA and the American College of Trial Lawyers.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine