Roll the tape

Effective use of videotaped depositions at trial

Depositions are often thought of as a discovery tool for you to get the defense’s position on liability and for the defense to learn more about your client’s damages. But depositions can serve another, more powerful purpose: to bring your client’s story to life at trial. Using video depositions can not only save you time and money, they can also help you curate your client’s story in an effective manner. This article will explore how to set up your video depositions for use at trial.

Procedural considerations

The Code of Civil Procedure lays out the requirements for videotaping a deposition, and you should ensure that your deposition notices include this language so that, even if you are not sure you will use the deposition at trial, you are not precluded from this down the line. You must list in your deposition notice that you intend to record the testimony by video technology, along with any intent to “reserve the right to use at trial a video recording of the deposition testimony” per Code of Civil Procedure section 2025.220.

Then, of course, make sure to book a videographer along with your court reporter for the deposition. While this is an added expense of the deposition, it will save you time and money in the long run as you will have the testimony preserved for trial.

If the deposition has been noticed by the defense and not by you, make sure to send a cross notice for video footage and confirm whether the defense has hired a videographer. If not, you will have to coordinate this on your own. Your cross notice should again state your intent to use the video recording at trial.

Consider taking depositions early in the discovery process. Not only defense depositions, but treating physicians, percipient and lay witnesses. By staying aggressive, you will get the testimony you need early and ensure that you are the noticing party and therefore in charge of the deposition and the questioning. While there might be temptation to wait until closer to trial in anticipation of the matter settling, the potential ramifications of not locking in the testimony might outweigh the small benefit in cost saving.

Remember, as time goes by witness memories fade or witnesses might not be available for trial. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 2025.620 [delineating the specific depositions that can be used at trial, including that of an adverse party, impeachment testimony of a witness, an unavailable witness, or a treating physician or expert].) Having the depositions done early will prevent any issues at trial in terms of presentation of evidence, and maybe you can even reach stipulations with the defense to play lay-witness testimony in lieu of calling them live, which will really save you time during trial, especially if witnesses would have to come to trial from far away.

Prepping for the deposition

For nearly all witnesses not represented by the other side, you should set up calls before the deposition to ensure that they know what to expect and generally the types of questions you will be covering with them. Not only will this help the deponent become comfortable with the process and talking about the subjects you need to cover with them, but it will also ensure that there are no surprises on your end. For example, the last thing you want is to depose a friend of your client who will talk about all the travel and activities they’ve seen your client do since the incident. Similarly, you don’t want to be blindsided by a doctor saying your client is an exaggerator.

The point is not to tell witnesses what to say or what not to say. Rather, the point is to do your information gathering early (and hopefully you have done this even earlier in the litigation process and have already vetted the witnesses as helpful for your case). This also gives you an opportunity to develop a rapport with your witness so that they are more at ease answering your questions during deposition, which can help with overall flow. I always tell my witnesses, “The only thing I am asking you to say is the truth.” And that way, if the defense asks about conversations that we’ve had, they can say “Teresa told me to tell the truth.” This lends to the objective and credible nature of their testimony.

I will also try to talk up the case a little bit to get the deponent engaged and to emphasize the value of their testimony. If the defense is trying to argue that the injuries are pre-existing or that the client is exaggerating, I’ll tell doctors that to put into context the importance of their testimony.

The preparation session is especially useful for lay witnesses (and some doctors) who might not be tech-savvy. You want to make sure that they have a good setup and internet connection so that the video footage looks professional and clear. Your videographer will also keep an eye on this during the deposition to ensure the connection stays stable. There might be exceptions to this general rule, however, if you have a witness whose credibility is in question but whose presentation and background might lend themselves to the story you are weaving.

The deposition

Start off your deposition by explaining to the witness that the reason you have a videographer present is to preserve the testimony for use at trial. This is especially important for depositions of treating physicians. Sometimes you might even catch the opposing attorney off guard if they were preparing only for this as a discovery deposition and weren’t ready to ask more trial-type questions, which can work to your advantage as you will be prepared. Always explain that, even though there is not a jury present, you might ask them to break down a medical term “for the jury to understand.” This will also serve as a useful reminder for the doctor throughout deposition to speak in more simple terms.

Rather than following a script, really try to have a conversation with the witness like you would at trial. Don’t be so beholden to your outline that you miss opportunities to ask follow-up questions. With treating physicians, I will usually place less emphasis on authenticating documents or going visit by visit and instead have a conversation about their overall treatment of the patient, what their goals were, what progress they saw the patient make or symptoms that persisted and refer to the actual medical records if they need to have their recollection refreshed or there’s some testimony I specifically need to elicit. I find that doing so allows the doctors to have a more genuine and less robotic conversation about patient care that plays better to a jury and is more interesting than “on ABC date, what did you prescribe for treatment?” which starts sounding repetitive after a while.

There are some questions that should be asked of all witnesses, such as on credibility. With friends or coworkers, this might be something like “is XXX a hard worker?” “Did you find them to be honest?” and having them expand on what they have observed.

With doctors, this should include questions like the following:

Did you find XXX to be credible?

Was she honest in her reports of pain to you?

Truthful?

Did you ever notate that XXX was not being truthful?

Did you ever find XXX to exaggerate any complaints?

During your treatment, did XXX’s subjective complaints align with your objective findings?

That was true throughout your treatment?

Her complaints were consistent?

What does malingering mean to you?

Did you find XXX to be a malingerer?

In addition, with your treating physicians, you should always ask about causation. Under Schreiber v. Estate of Kiser (1999) 22 Cal.4th 31, treating physicians may still provide opinions including on causation that are based on information learned during the treatment of the patient and independent of the litigation. (Id. at 39.) Consider the following:

Is it your opinion based on your treatment of XXX that their condition started with the subject incident?

Did XXX’s symptoms start with the subject incident?

Based on your examination and XXX’s presenting complaints, was the subject incident a substantial factor in causing XXX’s injuries? Harm? Condition? Symptoms? Pain?

But for the subject incident, would XXX have needed this treatment?

Was the treatment caused by the subject incident?

Think of as many ways as you can to ask the questions. Your goal should be to end up with the soundbites that you will play in opening and your case in chief where there is a single clear question and response with no interruptions or over-explanations. If it takes a few tries to get there, don’t worry. The nice thing about a deposition is that, within reason, you can take your time asking the questions and re-ask to get a clean version.

Creating the video

As you get closer to trial, start thinking about what portions of the depositions you want to use in your opening statement and case in chief. Code of Civil Procedure section 2025.620, subdivision (d) states that you can use the video deposition of a treating physician or an expert even if they are going to testify. In addition, section 2025.620, subdivision (b) allows you to use the deposition of an adverse party even if they will be or have already testified.

Notably, “a party may offer in evidence all or any part of a deposition, and if the party introduces only part of the deposition, any other party may introduce any other parts that are relevant to the parts introduced.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 2025.620, subd. (e).) Some judges may try to make you play all of the clips together, so be prepared if that occurs.

Using the video at trial

To determine which portions I want to designate for use at trial, I will go through a copy of the transcript and highlight or underline the questions and answers that I like. I am looking for clean questions and answers (if there are objections, that’s fine so long as the question and answer together would make sense). I tend to over-designate at first to err on the side of caution.

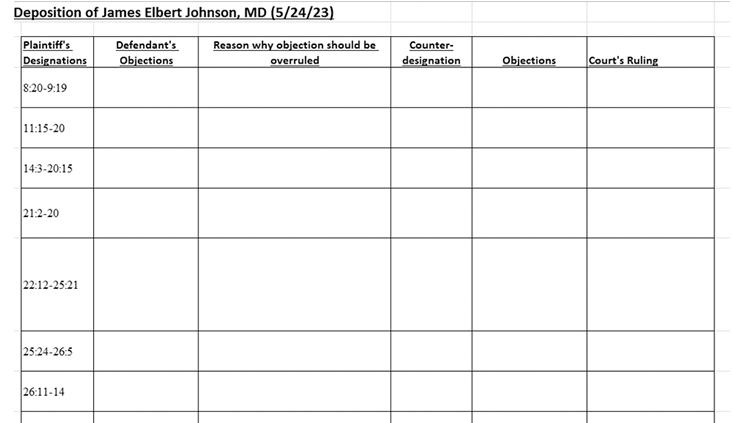

When I have my page lines ready, I prepare my notice of intent per Code of Civil Procedure section 2025.340 and serve this on the defense, usually about three to four weeks before trial. I then create a chart of video testimony such as the one below, which gets attached behind a cover sheet for filing.

I send this to the defense along with our other proposed trial documents for them to insert objections and counter designations, and then file with the other trial documents and include in the trial binder along with a color-coded copy of the deposition transcript designating both our and defense portions. Depending on your court, the judge might have more specific requirements on how they want the video designations prepared, so make sure you check and comply.

During opening, play clips from defense witnesses or experts to lock in what you believe the defense will say during trial. Maybe you have clips from defense witnesses that contradict each other or what the defense put in written discovery. Maybe you have testimony from the defense doctor that actually helps your case, such as the defense doctor agreeing your client is credible, or that the symptoms started after the incident. These can be short, 30 seconds to a few minutes in length, but are much more powerful than just clipping the transcript for jurors to read during opening.

Similarly, try to be mindful when creating your final videos of how much time you are spending on video footage. While you want to be thorough and make sure you get the evidence you need in, you don’t need to repeat facts with different witnesses as the jury will get the point. For example, you don’t need each treating physician to explain what a physical examination is or what subjective complaints and objective findings mean. If one doctor is going to explain what injections are and how they are performed, don’t use the same testimony again with another provider. Really try to streamline your videos that you intend to play in your case in chief so each one is no more than 20-30 minutes in length.

Some judges require that you play your designations in order, but if you can, try to move around portions of the video so that it makes sense and flows properly, grouping testimony together. Listen to the videos a few times before trial to make sure that the progression makes sense and have others listen as well.

Before trial, make sure to file a brief on the use of video testimony in opening statement and during your case in chief, citing to the code sections that permit you to do so. While most judges are familiar with video testimony, in the event you get any push back, the trial brief will ensure that your argument gets in front of the judge properly. At your final status conference or first day of trial, make sure your judge is aware of your video testimony so that he or she rules on the portions you intend to play before opening statement.

Conclusion

Litigation is so much more than a discovery process. It is essential you use the time you have in litigation to set yourself up for success at trial. With early planning, you can and should be able to craft effective video depositions for use at trial.

Teresa Johnson

Teresa Johnson is a trial attorney and partner at Kramer Trial Lawyers. She currently serves on the 2024 CAALA Board of Governors and as the co-vice chair of the Education Committee.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine