Tips from a prosecutor turned plaintiff’s counsel

Leverage courtroom dynamics to secure justice for personal-injury clients

The courtroom is a trial attorney’s classroom. There is no better training ground for a trial attorney than being in court, trying cases. We can go to all the conferences, listen to all the podcasts, and read all the books (or articles like this one!) but the best education truly comes from inside the courtroom.

If you wanted to be a football player, you wouldn’t just read a book about football, you would get on the field and play. Because criminal jury trials happen more frequently than civil trials, the fastest way to get experience trying cases is to join the District Attorney’s Office or the Public Defender’s Office.

I spent almost 15 years prosecuting criminal cases before leaving the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office to start a new career as a plaintiff’s personal-injury attorney. I am often asked how criminal trials differ from civil trials. The short answer is “not much.”

As a prosecutor, I helped people who were victimized by the defendant’s criminal conduct. Now, as a plaintiff’s attorney, I help people who were victimized by the defendant’s negligence. Both have allowed me to secure justice for those harmed through no fault of their own by holding the responsible actor accountable.

As for the differences, I have had to get used to having fewer peremptory challenges – most of my criminal trials were homicides or child molestation which allowed me 20 peremptories, and creating a separate written document for each motion in limine, (in criminal, I drafted one trial brief that had all motions in it), and going first during voir dire. On the flip side, I enjoy the benefit of a lower burden and needing only nine (state court) jurors to agree with me instead of having to convince all 12. The procedural differences generally end there. The art of storytelling, connecting with jurors, and knowing your case better than opposing counsel are equally essential regardless of the type of trial.

It is presumably unrealistic for you to drop your civil litigation practice to join the District Attorney’s Office or Public Defender’s Office for the next five years to gain trial experience. Instead, here are some insights I’ve drawn from my criminal trial experience that you can apply immediately to sharpen your civil trial skills.

Voir dire with hypotheticals

Most people dread jury duty. Think about how often the non-lawyers in your life ask, “You’re a trial lawyer, can you tell me how to get off jury duty?” You may be thrilled that your case is finally going to trial, but your prospective jurors are not. They are not happy to be there and are particularly annoyed that they cannot be talking on or scrolling through their phone during jury selection.

The first opportunity you have to win over jurors is by making the selection process more interesting than the judge did before you by “going through the questions on the board” to get everyone’s demographics. The process of civil jury selection is governed by Code of Civil Procedure section 222.5 and subdivision (b)(1) provides that, “upon completion of the trial judge’s initial examination, counsel for each party shall have the right to examine, by oral and direct questioning, any of the prospective jurors in order to enable counsel to intelligently exercise both peremptory challenges and challenges for cause.”

While judges often focus solely on whether an attorney’s voir dire is relevant to the question of cause, section 222.5 specifically gives counsel the right to examine jurors for both peremptory and cause challenges. The code defines “improper questions” as those that “precondition” or “indoctrinate” the jury, but there is no statutory requirement that voir dire must be boring. Nor is there any prohibition on utilizing hypotheticals to examine jurors for both peremptory and cause challenges.

Hypotheticals are engaging and get jurors talking. By using hypotheticals, you can see how potential jurors discuss and work through questions, rather than yielding only “yes and no answers” or telling you their favorite travel destination (sidenote: Please never ask jurors this. Many of them may not be able to afford to travel and by asking this question you merely demonstrate that you are a rich and out-of-touch lawyer).

When using a hypothetical in voir dire, the facts must be dissimilar to those in your case. This keeps you out of the fray from “indoctrinating” and “preconditioning.” While the facts of your hypothetical will be different from those in your case, the fundamental issue you are inquiring about will be the same.

In the criminal context, I often needed to learn which jurors would (and would not) understand that when witnesses to a gang shooting testified inconsistently with their previously recorded statements to the police, it was because they were afraid of retaliation from the gang and not because what they had told police was untrue.

To evaluate prospective jurors’ thoughts about recanting witnesses, I asked them to assume the trial was a domestic violence case rather than a gang shooting. The victim in our hypothetical case originally called 911 screaming for help because her boyfriend had cut her with a knife. When the police responded, the victim was locked in her bathroom crying and police observed a bleeding knife wound on the victim’s arm. A year later, when that case went to trial, the victim testified in court that her boyfriend would never hurt her and the knife wound was a result of her accidentally cutting herself while cooking.

I would ask jurors if they could think of any explanation for why the hypothetical domestic violence victim was testifying inconsistently with her original call for help. Using this hypothetical got jurors talking about fear of retaliation and other reasons witnesses may recant. It also allowed me to ensure that I was selecting jurors who understood such an important concept to my gang-shooting case.

In a personal-injury case, we want jurors willing to give our clients “full justice” not “discounted or partial” justice. We also want jurors not to be concerned with an individual defendant’s perceived lack of wealth since we are not allowed to tell them that a large verdict would not bankrupt the defendant but would teach the insurance company a lesson. You can get jurors talking about both of these issues by posing a hypothetical rooted in a fact pattern unrelated to any of the injuries or facts in your case.

Give the jury panel a hypothetical about a kid playing catch with his dad. The kid throws a little too long and the ball goes through the neighbor’s window, damaging the television. Do you think the kid (or his parents) should have to replace the neighbor’s broken window? Would it be sufficient to just put up some cardboard and duct tape on the window? Why not? What about the broken television, should that also be fixed or replaced as needed? Why or why not? What if it was a financial hardship for the kid’s parents to make that type of restitution? Is the neighbor just out of luck at that point or is there another solution?

By posing this hypothetical, you will get jurors talking about what full responsibility means to them. Ideally, your panel will contain many jurors who strongly believe it is important to not only “take responsibility,” but also to “make things right” rather than jurors who demonstrate so much empathy for the kid and his father that they will chalk up the neighbor’s loss to “accidents happen.”

The use of a hypothetical in voir dire not only assists in the identification of good and bad jurors for your case, but also allows you to set up themes that you will return to in closing argument. You will remind jurors of your discussion with them during jury selection. Much like the neighbor and the kid who broke his window, the defense should take full responsibility for the harm caused and make the plaintiff whole. To earn extra credibility points, you can draw the analogy further by telling jurors your client is merely asking to be made whole, for the defendant to pay for the broken window and television; not to remodel the whole house.

Be civil to opposing counsel

Jurors do not like jerks. Jurors will notice not only how you treat them during voir dire, but also how you treat the judge, the judicial assistant, and the courtroom attendant or bailiff. The jury will especially notice how you treat your adversary throughout the trial. It’s remarkable how much more amicable the relationships between opposing counsel are in criminal cases compared to those in civil litigation.

In criminal, prosecutors and public defenders are assigned to a particular courthouse and often to a specific courtroom. Daily contact with your adversary (on not just one case, but many of your cases) necessitates mutual respect and professionalism. Because today’s criminal defendant could easily be tomorrow’s victim (and vice versa), criminal attorneys are frequently forced to shift their perspective, allowing them to understand the other side more fully.

In civil, plaintiff’s attorneys seldom represent corporations or public entities, let alone insurance companies. While defense counsel may represent an insured individual, they are never in the position of seeking financial compensation for that client. As lawyers, we know that it is imperative to anticipate your adversary’s arguments, but we often fail to put ourselves in their shoes. As Atticus Finch told Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, “You never really understand a person until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.”

We hold enormous empathy for our clients and yet we rarely extend such grace to our opposing counsel. Much like our country’s current political parties, plaintiffs’ and defense attorneys are deeply divided. The demonization of “the other side” is not only polarizing, but also paralyzing. Ever tried to get joint trial documents prepared with an opposing attorney who will not even return your calls or emails? When the defense views you as “nothing but an ambulance chaser” and you view the defense as “billing robots for morally bankrupt insurance companies,” productivity stalls out, and ultimately, the client suffers.

Civility is not a sign of weakness. You can fiercely advocate for your client and still treat your adversary respectfully. The two are not mutually exclusive. You can and should do both. Being kind to opposing counsel is not just about decorum – it’s about ensuring that the pursuit of justice remains productive, focused, and truly in service of those we represent.

Subpoena medical bills directly to the court

Prosecuting violent crimes where victims sustained great bodily injury necessarily required obtaining the victim’s medical records. To do so, a subpoena duces tecum under Code of Civil Procedure section 1985.3 (“SDT”) was personally served on the medical facility where the victim received treatment. In the subpoena, the hospital is given a choice in how to respond. They can either send a custodian of records to personally appear in court with the requested records on the date noticed, or they could send only the records directly to the courtroom with a completed custodian of records declaration. Guess which option the medical facilities always select?

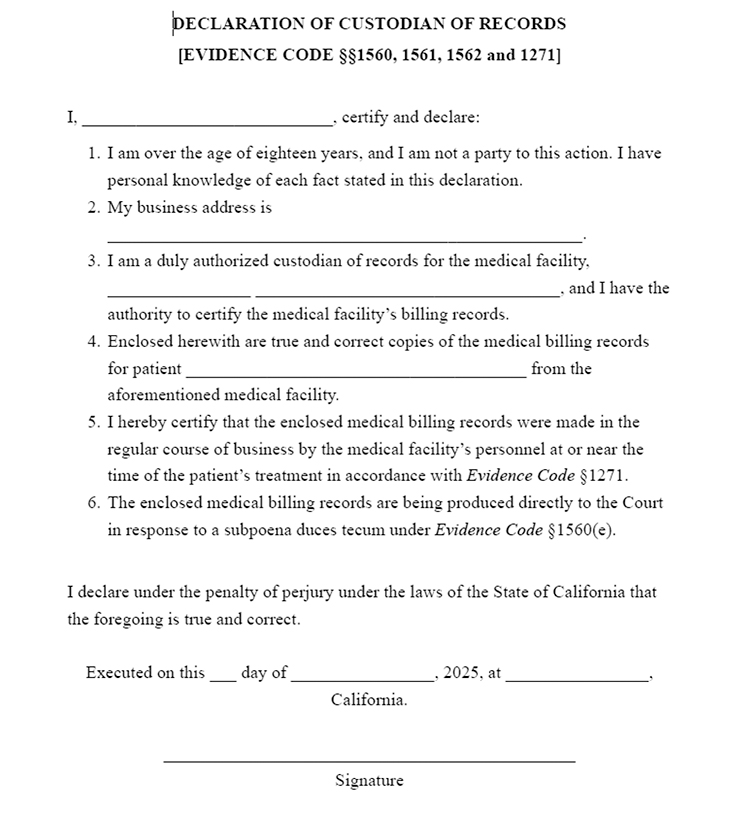

For the records to be admitted as evidence without having live testimony from the custodian, the declaration must comply with Evidence Code sections 1560, 1561, 1562 and 1271. Doing so will establish both the authentication for the records and overcome hearsay via the business records exception. Both the records and the declaration must be placed in a sealed envelope that is then placed in an outer envelope and mailed directly to the court to preserve the chain of custody. Here is the sample declaration I provide with my SDT for the custodian to execute and return to the court with the records (See page 102).

Summarizing medical bills for the jury

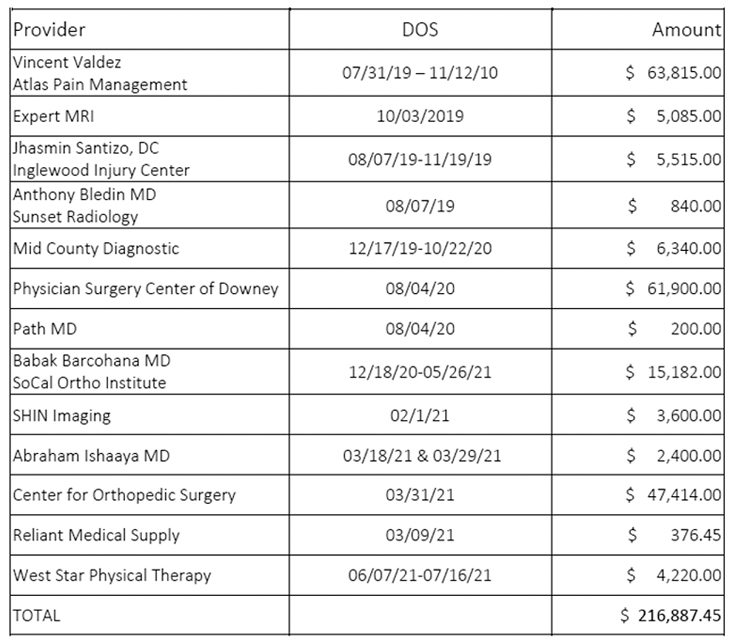

In a personal-injury trial where the plaintiff is claiming past medical expenses as part of their economic damages, it is necessary to ensure that the jury knows the total amount of your client’s medical bills. If you’ve been civil with defense counsel, you may be able to stipulate to the admission of an exhibit that lists your client’s medical providers, the date of service, and the billed amounts. (See example on page 106).

In proposing this stipulation, I tell defense counsel they can still argue that the medical treatment and/or the billed amounts were not reasonable and necessary. The stipulation to this exhibit simply alleviates the need to parade each custodian of record into court to testify.

By subpoenaing the bills directly to court, you are ensuring their admissibility, but not necessarily presenting the bills themselves to the jury. It is preferable to most plaintiffs’ attorneys that the jury never see the bills themselves (since they are often addressed to the attorney or have insurance or other confusing information on them) and only hear the final amounts via testimony from the plaintiff, a billing expert, or the treating doctor. When you use a subpoena duces tecum for the bills, however, you will find that the same defense counsel who initially refused your proposal to stipulate to the billing chart will miraculously change their mind once they see that their refusal to stipulate did not actually prevent you from getting the amount of your client’s medical expenses into evidence.

Master the Evidence Code to stay agile

Discovery in criminal cases typically includes police reports, transcripts of witness interviews by police or other investigators, photos, videos, and scientific expert reports, but not depositions. That’s right, there are no depositions in criminal cases. When the attorneys for each side question a witness in a criminal case, it is always done in court before a magistrate. Proceedings such as preliminary hearings and motions to suppress give criminal attorneys regular practice at honing their skills questioning witnesses and responding to objections.

In civil, witnesses are primarily questioned at depositions where limited objections are made, and when they are made, the witness typically still answers the question. Such “objecting into the wind” limits civil attorneys from learning how to deal with sustained objections. Unlike a deposition, simply repeating the question the same way after an objection will not work when questioning a witness in court.

Laying foundation and phrasing questions in such a way as to avoid sustained objection requires both knowledge of the Evidence Code and practice. When defense counsel interrupts your direct examination at trial with meritless objections, it is annoying. But when sustained objections stop your evidence from coming in all together, it can be fatal to your case. Knowing the Code will allow you to be agile enough to pivot.

When you hear the judge say “sustained,” consider the grounds for the objection before you ask your next question. Rephrasing will only work when it was truly your question, rather than the evidence being elicited that caused the judge to sustain the objection. Re-reading and annotating the Evidence Code may not be necessary depending on your year of practice or experience level, but making a “key objections cheat sheet” for your trial notebook that you review at the start of each trial could enhance your proficiency.

Go watch and be watched

When I was a deputy district attorney, my office was in the courthouse where I tried cases. Having an office in the courthouse made it extremely easy to watch colleagues in trial. Observing different attorneys try cases provided an invaluable masterclass in trial advocacy. By watching others, you can steal what works for you and leave what doesn’t. Do not limit yourself to watching only the heavy hitters; watch all different types of lawyers. Sometimes learning what not to do is just as valuable as what to do.

In civil, big trials may get publicized on television or the internet, but such trials only show the judge and attorneys, never the jurors. Sitting in the courtroom gallery allows you to see how jurors react to the evidence and arguments presented.

Similarly, when I was in trial, I greatly benefited from having my peers in the courtroom to take notes and give me feedback. How did the jury react to the defendant’s testimony? Which jurors do you think are with me? Which ones are not? How did the victim come off? Was the expert clear in explaining the science?

This dynamic of peer observation and feedback is often missing in civil trials, but its value cannot be overstated. Making time to observe your colleagues in action can offer fresh perspectives on jury behavior and courtroom dynamics that you can incorporate into your own practice. Likewise, inviting trusted peers to sit in on your trials and provide honest feedback will help you understand how your case is or is not resonating with the jury.

Trial lawyers tend to carry their egos into the courtroom, which can fuel their confidence, passion, and determination to fight for justice. But the best advocates understand that win, lose, or hang, every trial provides an opportunity to learn something new and every colleague or opponent is a potential teacher.

Allyson Ostrowski

Allyson Ostrowski spent almost 15 years as a Los Angeles County deputy district attorney before switching to civil practice. She has tried over 65 cases to verdict, including both criminal and catastrophic personal injury cases. Allyson is a trial attorney at Abir Cohen Treyzon Salo, LLP. She loves talking trial strategy and voir dire hypos, so reach out to her at aostrowski@actslaw.com.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine