Construction-site injuries

A guide to key discovery through voir dire

The chaotic scene of a construction site can have multiple people responsible for different jobs, working for different companies, all with their own interests. And in the middle of everything, your injured client. It’s up to you to navigate through the potential parties, identify the key issues, and gather the ammunition needed for trial. And just like any case, it begins in discovery. An effective discovery strategy in construction cases can prepare your case for trial by identifying the players, defining your theory of liability, and focusing-in on the main issues. In this article, we will discuss key techniques to take you from discovery through voir dire and to set yourself up to put on your best case at trial.

Discovery in construction cases

Construction cases tend to have multiple parties present in the area where an injury occurs, with varying levels of duties and responsibilities. This invariably leads to a lot of finger-pointing, which can make it difficult to determine which defendant(s) to focus on and how to clearly define your theory of liability. Strategic use of written discovery can help identify the essential parties, clarify roles and relationships of the defendants, flesh out policies and procedures, find persons most knowledgeable, and avoid construction-specific case pitfalls.

Many of the examples in this article come from a trial we had involving our client falling into an open trench, but these can be easily modified to whatever dangerous condition your client confronted.

Identify essential parties

One of the first steps in a construction case is to find out all the parties that may have worked in the area or on the object in question. Beyond the obvious of identifying potential defendants, understanding the parties can help you get an idea of how the construction site operated and the interests of the parties involved. For example, it may be much easier to obtain a key answer or document from a less culpable party if that party feels the information provided can help get them off the hook. Ask for the identity of any documents that will list all parties involved. Try the following:

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY:

Please IDENTIFY all contractors, companies, and/or business who performed any construction services on the SUBJECT PREMISES during the one (1) year period preceding the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION: Any and all construction reports and logs RELATING TO the construction work in progress at the SUBJECT PREMISES from January 1, 2019 to the present.

Roles and relationship of defendants

In a scenario where everyone is blaming each other, it is important to understand who was responsible for what. Use discovery to establish the relationships between contractors and subcontractors and learn the scope of work for each party. Ask interrogatories that delve into specific responsibilities related to your incident. Requesting contracts and agreements can help you understand the agreed-upon duties and responsibilities of the parties. Start with more general discovery but remember to focus on the specific condition or defect to narrow in on the potential liable parties. In the context of our trench case, it was important to lock in defendants as to their responsibilities relating to the trench and, if necessary, pit one defendant against the other. Sample discovery includes:

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: Please state YOUR relationship with the owner of the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: IDENTIFY all PERSONS who you contend were responsible on the date of the SUBJECT INCIDENT for ensuring that the SUBJECT TRENCH was not left in a dangerous condition.

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: IDENTIFY any and all PERSONS who you contend were responsible for covering any holes, trenches or other depressions in the ground including the SUBJECT TRENCH on the date of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION: Any and all contracts between YOU and any contractors, companies, and/or business RELATING TO constructions services for the SUBJECT PROJECT.

Policies and procedures

Along with understanding the duties and responsibilities of the parties, it is important to learn what policies and procedures are in place to dictate how those duties are executed. Getting this information helps lock down each defendant as to how they should have conducted themselves during the incident. Along with policies and procedures, understanding how, when, and if safety meetings were held are important knowledge in construction cases. Request safety meetings notes and attendance sheets and ask detailed questions regarding who conducted, ran, and attended those meetings.

Many times, certain crews will have safety meetings regarding a specific aspect of the construction. For example, a contractor may hold a safety meeting about open trenches before trench-digging commences on site. Having these verified responses when you begin taking depositions allows you to determine whether the parties followed their own policies and procedures. It is also important to note that a lack of policies, procedures, and safety meetings can be just as telling and vital to your case. Here are some examples of what to ask:

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: Please IDENTIFY any and all policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rules regarding the digging of trenches including the SUBJECT TRENCH at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: Please IDENTIFY any and all policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rules RELATED TO YOUR safety of open trenches at unfinished construction sites including the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: Please describe any and all training procedures, which are followed in the course of training YOUR employees or contractors RELATED TO covering trenches, holes or depressions including the SUBJECT TRENCH on the SUBJECT PREMISE. This includes and all written material, slides, photographs, films, videotapes, etc., which defendant utilizes in training its employees.

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: IDENTIFY any and all policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rules regarding safety while constructing the PLATFORM in effect at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION: Any and all DOCUMENTS from YOUR safety meetings, including but not limited to safety meeting reports, RELATING TO the SUBJECT PREMISES from December 1, 2017 to December 15, 2017.

REQUEST FOR PRODUCTION: Any and all DOCUMENTS RELATING TO YOUR policies, procedures, and rules on the construction of trenches, including the SUBJECT TRENCH, at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

Persons most knowledgeable

As good as written discovery can be, the ability to ask questions in real time at a deposition can be even more powerful. In order to ensure you are speaking to the right people, it is important to identify the persons most knowledgeable in key categories to depose. Use written discovery to determine who these persons are. The PMK of policies, procedures, and safety meetings is a good way to get the answers you need and identify if the testimony deviates from the defendant’s written discovery responses. Don’t forget to utilize any experts you have retained on your case to generate important PMK categories. Here are some examples:

SPECIAL INTERROGATORY: Please IDENTIFY the PERSON(S) most knowledgeable regarding policies in place for safety during the construction of the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

PERSON MOST KNOWLEDGABLE OF THE FOLLOWING SUBJECTS:

Defendant’s CONSTRUCTION PLANS for the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISES.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rules for safety for the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rules regarding warnings, caution, and notification of ongoing construction for the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, forms, methods, and rule RELATED TO YOUR employee injury prevention of the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

Defendant’s contracts and agreements with subcontractors RELATING TO the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, and rules related to employee injury prevention at the SUBJECT PREMISE at the time of the SUBJECT INCIDENT.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, and rules RELATED TO trench safety.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, and rules RELATED TO excavating and working in trenches.

Defendant’s policies, guidelines, procedures, and rules RELATED TO notifying PERSONS about trenches at the PROJECT at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

Defendant’s distribution of job site duties at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

The SUBJECT TRENCH at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

Covering the SUBJECT TRENCH at the SUBJECT PREMISE.

Subpoenas and OSHA reports

In construction cases, using the Defendant’s obligation to report to regulating bodies such as OSHA (Occupational Safety & Health Administration) can be incredibly useful. Being a third party, OSHA is less likely to be as resistant to handing over documents as a defendant. The documents produced, any investigations, or opinions can be helpful in establishing how the defendant(s) may have breached their standard of care. The OSHA investigator may have interviewed key witnesses, which gives you a head start on identifying the persons you will want to speak with as well. You may also find discrepancies between documents the defendant provided to OSHA and what was produced in discovery responses. You may even find instances where information obtained through depositions or written discovery proves that the defendant provided false information to OSHA following the subject incident.

OSHA reports may not always be beneficial to your case. As discussed below, there may be reasons and strategies for keeping OSHA documents out of trial. Yet, it is a good idea to remember to subpoena these reports when available.

Prepare for Privette

In construction cases, there is often interaction between the property owner, contractors, and subcontractors. In these scenarios, you are going to be faced with the Privette doctrine. The subject of Privette warrants a dedicated article, which can be found in earlier issues of this publication. Among other things, the Privette Court held that a hirer is typically not liable for injuries sustained by an independent contractor or its workers while on the job. (Privette v. Superior Court (1993) 5 Cal.4th 689.) The Supreme Court has identified exceptions to Privette outlined in Hooker v. Department of Transportation (2002) 27 Cal.4th 198 and Kinsman v. Unocal Corp. (2005) 37 Cal.4th 659. While it is important to consider Privette before taking on a construction case, it is also a good idea to be mindful through discovery and request information that will bolster your Hooker or Kinsman arguments in the event of a defense motion for summary judgment. As Hooker and Kinsman exceptions hinge on establishing which parties had notice and control, be sure to tailor your discovery to target that information.

Using written discovery at trial

In construction cases, written discovery can help guide the jury through the world of a construction site, including various policies and procedures that govern a job site as well as the main players in your case. Therefore, it is important to start early on your trial plan to see how discovery can fit in to your case.

In the 90 days before trial, take stock of the discovery you have to date, and determine whether you need to send any final rounds of questions to lock in the defense to their position on liability, causation and damages. In the context of construction cases specifically, consider whether you have asked sufficient questions regarding safety meetings, control of the job site, applicable IIPPs and other manuals, etc. At this point, you should already have a solid handle on the defendants’ positions on liability and causation. Use final discovery to lock them into their position on damages, and to ensure they do not want to change any prior answers.

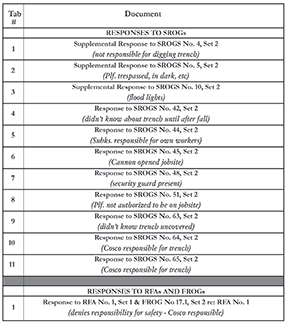

To use discovery at trial, you do not have to identify the sets on your exhibit list. Instead, file a trial brief on the issue of displaying discovery at trial, and cite the relevant code sections that govern use of discovery at trial. (Code Civ. Proc., §§ 2030.410, 2033.410; see CACI 209 and 210.) Then prepare Discovery to Display binders that make it as easy as possible for the judge and opposing counsel to follow along with the discovery you want to display to the jury. In these binders, you will place the typed question and response on plain page; cover page of the response to discovery; page(s) of the actual discovery response; verification page. Omit objections from the typed page so that it is clean when it is shown to the jury. Each discovery response is set behind its own tab in the binder for easy access. The tabs correspond to the Table of Contents (see example), which sets forth a brief description of the question and answer.

As you can see from the sample, in this case, the general contractor defendant was denying responsibility for the dangerous condition (a trench in the middle of the walkway path that our client fell into while walking into work one morning). The general contractor also stated in discovery that Plaintiff was trespassing, and that the subcontractor who dug the trench (Cosco) was the only party responsible for safety of the trench. Not surprisingly, the subcontractor said almost the exact opposite.

Being able to juxtapose the general contractor’s responses against the subcontractor’s responses in opening statement was extremely powerful, as it all tied into our theme of failing to accept responsibility and pointing the finger at everyone else. When a worker falls into an uncovered trench on a jobsite, someone has to be at fault, and the written discovery was key in getting the jury fired up about the defendants’ refusal to accept liability. These responses under oath were also used with witnesses during their testimony to further emphasize the wrongdoings of the defendants.

Special considerations for OSHA Reports at trial

OSHA Reports detail investigations by an OSHA representative into how the incident occurred, as well as any findings and recommendations by the investigator. Inevitably, one side will find the OSHA Report to be useful, while the other side will want to exclude it at trial. (See also the article on Cal/OSHA in this issue.)

California Labor Code section 6304.5 states:

It is the intent of the Legislature that the provisions of this division, and the occupational safety and health standards and orders promulgated under this code, are applicable to proceedings against employers for the exclusive purpose of maintaining and enforcing employee safety. Neither the issuance of, or failure to issue, a citation by the division shall have any application to, nor be considered in, nor be admissible into, evidence in any personal injury or wrongful death action, except as between an employee and his or her own employer…The testimony of employees of the division shall not be admissible as expert opinion or with respect to the application of occupational safety and health standards.

Under a strict reading of section 6304.5, it may be possible to exclude at least the OSHA Report findings and any testimony by the investigator on the OSHA standards that may have been violated. However, courts have interpreted section 6304.5 to permit introduction of OSHA provisions to establish standards and duties of care.

In Elsner v. Uveges (2004) 34 Cal.4th 915, the California Supreme Court held that section 6304.5 was intended to allow parties to use OSHA provisions (including Labor Code sections, rules and safety orders promulgated under Cal-OSHA) to establish negligence per se. (Elsner v. Uveges (2004) 34 Cal.4th 915, 935-936.) Notably, however, Elsner does not state that the OSHA Report itself, the issuance of citations (or failure to issue citations), or the testimony of the investigator as to what findings he or she made, are admissible. Be mindful of general hearsay rules and exceptions to either fight to admit or exclude the findings within the report, especially in light of the plain words of section 6304.5.

Construction voir dire

When approaching voir dire in a construction case, as in all cases, you want to start with a list of topics that keep you up at night: the areas that you’re worried defense-minded jurors will latch onto and try to sink your case. In most of our construction trials it comes down to these:

Property owners responsible for every inch

Comparative fault/personal responsibility/construction sites dangerous

Importance of rule-following in the workplace

Based on the discovery you’ve conducted in your case during litigation, you should be well aware of these issues as you approach trial and should start thinking early about how you want to address them in voir dire.

Property owners responsible for every inch

Before you get into specifics on construction sites, you want to gauge who is turned off by premises cases in general and who thinks the burden is too high on property owners/managers. Here is sample voir dire:

Who here thinks property owners should be required to keep every square foot of their property safe for the public?

Who thinks a little different, and that’s too much of a burden to place on property owners?

This will put the jurors in the shoes of the public or the property owner, which should provide solid insight into the juror’s feelings. From here you want to move into worker/professional safety on properties:

I’m sure all of you have, at some point, hired a professional service person to do work on your home or your property that had some potential hazards, correct?

Let me ask each of you: When they showed up, if there were any hazards that only you were aware of – let’s say a hole in your attic, or a big dog in your yard, or some wires without insulation – did you tell them about it, or because they were a professional did you expect them to figure it out for themselves? Why did you tell them, even though they might have figured it out themselves?

Comparative fault/personal responsibility/construction sites dangerous

One of the biggest concerns in these cases is that jurors believe workers should be extremely careful because construction sites are inherently dangerous, and workers basically assume the risk. Here are some sample questions to help find out who leans that way:

How many of you have ever worked in a dangerous job or worksite where it was 100% your own responsibility to keep yourself safe? What kind of daily safety precautions do you take?

Has anyone here ever worked at worksites that had major hazards that you had to keep yourselves safe around, instead of expecting your company to protect you from them? Tell me about that. Do you think your company should have fixed or removed those hazards?

Let me use an example: Let’s say there’s a huge open, deep hole on a construction site without anything blocking it off. The workers know it’s there and try to stay clear of it… but a few weeks into the job, a worker falls in and gets hurt. Who feels like it’s always the worker’s fault for getting hurt in a situation like that, not the company’s fault for choosing not to fix or block off the hole?

Some people believe that personal responsibility means that if you make a mistake, you accept your full share of the responsibility for it. Some people believe it means that if you make a mistake and get hurt, you should only blame yourself 100%... even if others made mistakes that also caused the problem. What are your feelings about that, do you agree or disagree?

If it helps, I’ll give you an example: Let’s say a driver is drunk and going 70 mph through a green light… and a truck driver runs a red light and T-bones the driver. Who feels like the drunk, speeding driver should only blame himself… and would be irresponsible to file a lawsuit against the truck driver, even for a part of the blame?

One of the laws this jury will be asked to enforce has to do with shared responsibility. So, let me ask you directly: If you hear the evidence and decide that the property owner and Mr. Acosta both made careless mistakes, how many of you feel like it would be wrong for Mr. Acosta to file this lawsuit and ask a jury to also hold this company partly responsible… no matter what they did or didn’t do?

Importance of safety rules

Construction cases are some of the most “safety rule” heavy cases on our dockets. For this reason, you want jurors who believe safety rules, particularly in the workplace, must be followed to a T, because these will be jurors likely infuriated by the defendants’ failure to follow the rules.

Here are some examples:

I want to talk about workplace safety rules, practices or guidelines. Who works in a place that has safety rules?

Why are those rules important?

What happens at your work when those rules are not followed?

Do you see co-workers or other contractors fail to follow safety rules?

How does that make you feel?

Conclusion

Construction cases require careful planning early on, and a firm hand on discovery. However, these early efforts can pay off, as you wield all the information that you have gathered in voir dire and your case in chief.

Dan Kramer

Daniel Kramer is the founder of Kramer Trial Lawyers A.P.C. in Westwood, Los Angeles. He practices exclusively plaintiff personal injury and employment law. He served as President of LATLC in 2021 and currently serves on the CAALA Board of Governors. In 2021 he was a finalist for CAALA’s Trial Lawyer of the Year.

Teresa Johnson

Teresa Johnson is a trial attorney and partner at Kramer Trial Lawyers. She currently serves on the 2024 CAALA Board of Governors and as the co-vice chair of the Education Committee.

Brandon Salumbides

Brandon Salumbides is a trial attorney at Kramer Trial Lawyers A.P.C. in Century City. A graduate of Southwestern Law School, Brandon’s practice is focused in the area of personal injury.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine