Humanizing the plaintiff in civil-rights trials

Whether it be a plaintiff with a criminal history, or issues with substance abuse, the jury’s perception is one that must be shaped from the inception of the case

“Momma, I love you. Tell my kids I love them. I’m dead.” – George Perry Floyd, Jr.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was arrested by Minneapolis Police Department Police Officer Derek Chauvin. Following the arrest, Officer Chauvin proceeded to kneel on Mr. Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds, asphyxiating him and killing him. Why was he arrested? A store clerk suspected Mr. Floyd might have used a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill. I’m going to repeat that: A store clerk suspected Mr. Floyd might have used a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill. Ten months later and the wrongful-death lawsuit settled for $27 million.

But one has to wonder what would have happened had the attorneys tried the case? Would the jurors have been swayed by the defense attorneys’ defamatory characterizations of Mr. Floyd? What about evidence of Mr. Floyd’s criminal background? Let me ask it this way: Does the fact that from 1997 to 2005, Mr. Floyd served eight jail terms on various criminal charges, including aggravated home invasion and drug possession, make his life less valuable? My answer, as a civil rights attorney who specializes in police shootings and jail death cases, is a resounding “NO.” But I’m not a juror. And so, how do I convince jurors to see my clients the way I see them with no judgment, with empathy, and with love? I’ll show you…

Perception: Internal and external

A true storyteller is one who can humanize a person – any person, no matter the walk of life. My role as a storyteller begins the second a family hires me as their civil rights attorney. This means I come prepared for the initial meeting with the objective of finding out who their loved one was and what their loved one meant to them. I want to know what their son’s hobbies were and what sports he was good at. I want to know what was the funniest memory they have of their daughter.

And just like I want to know the good, I want to know the not-so-good. I want to know when was the last time they saw their son, and what may have drove him to abuse drugs. I want to know when they began to notice that their daughter was hanging out with the wrong crowd. This is the very information I need to begin my own humanizing process to help shape my own perceptions of the decedent.

Now, comes the hard part. How do I influence public perception for folks who are not like me, i.e., a Latina civil rights attorney who was born in East Los Angeles in a Mexican immigrant household. Well, that’s where the rubber meets the road, i.e., “ahí está el detalle.”

I begin with the media. The media is the single most powerful tool to claim and then reclaim the narrative in your civil rights cases. My cases fall under two categories: police shootings and jail-death cases. From the very inception, the media plays a huge role for both types of cases.

In police-shooting cases, it is mandatory for the involved law-enforcement agency to release a “critical incident video” within 45 days of the shooting. This video captures everything and anything that has to do with the “critical incident,” including the circumstances before, during, and after the shooting, and of course, the decedent’s criminal background dating all the way back to their teenage years. The effect this has on the public’s perception is simple. Not only was it Mr. Gonzalez who was shot and killed by the LAPD on January 1, 2024, it was Mr. Gonzalez “who was a career criminal, in and out of the prison system since the age of 19” who was shot and killed by the LAPD on January 1, 2024. You see the difference?

In jail-death cases, the public’s perception is unfavorable from the beginning given the fact that the case involves an inmate who died in a jail. And that’s enough to carry the negative perception through trial.

The press conference

So, how do I shape the narrative from the inception of the case? Two words: Press. Conference. My practice is to hold a press conference as soon as possible in all of my cases. The press conference is not only my opportunity to tell the public the wrongs that were committed which resulted in Mr. Gonzalez’s death, but also the family’s opportunity to tell the public just how loved and cared for Mr. Gonzalez was. As human beings, it is relatively easy for us to watch a news story and feel a sense of sadness about another person’s tragedy, but it is entirely something else to feel empathy for that person by truly putting ourselves in their shoes.

I have found that at a press conference, when Mr. Gonzalez’s mother shares her grief by telling the media how much she’s going to miss her son telling her that he’d like eggs but without onions for breakfast, mothers all over California will look over at their sons and imagine an empty chair at the breakfast table. To me, that’s the closest I’ll get to humanizing Mr. Gonzalez before trial.

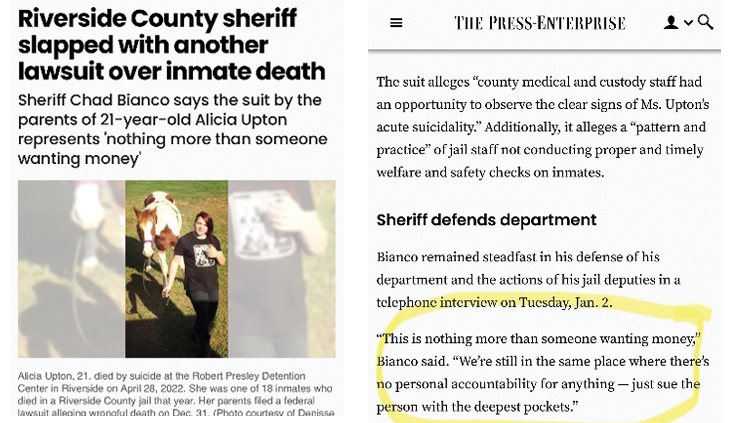

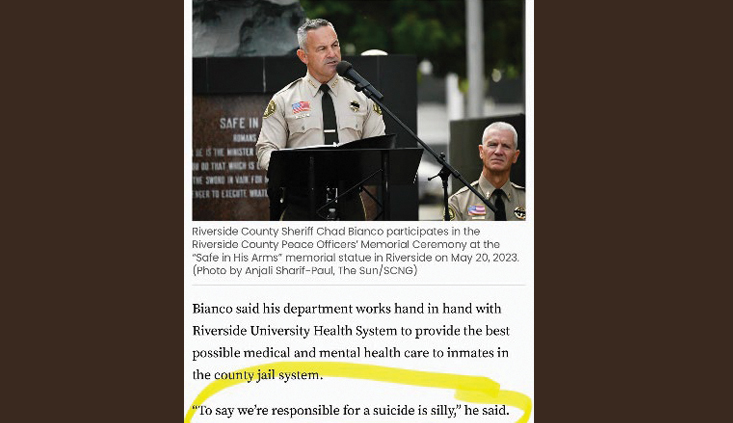

Following the press conference, I will engage the media further by crafting a social-media post that is dedicated to the decedent and the family. I will utilize photographs of the decedent to humanize the post. This is also an opportunity to set the record straight as to misrepresentations made to the public by the involved law enforcement agency. An example of this would be an Instagram post I crafted for my beloved Alicia.

Here is the post:

“Let me tell you about Ali …

Alicia (“Ali”) Upton was known for her great sense of humor and infectious laugh. As a child, Ali was a talented dancer, who loved performing in recitals. She’d light up any stage with her magnetic energy. Having grown up in West Virginia, Ali’s love for fishing, hiking, camping, swimming and horses came naturally. She also loved gazing at the moon. Some of her mother’s most cherished memories of Ali are the times that they would gaze at the moon together, whether it be in person or on the phone. It was comforting that despite how far away they were from one another, they could always gaze at the moon at the same time.

On April 21, 2022, Ali was taken into custody at the Riverside County Jail. Despite having expressed suicidal thoughts (e.g., “I kinda always wanted to die”) at booking, and despite obvious signs that Ali was acutely suicidal and engaged in self-injurious behavior (e.g., “severe” mental health rating, 20 visible cut marks on her left arm), Ali was placed in a cell which was known to pose risk of death to suicidal inmates by virtue of the hazards contained in the cell. On April 28, 2022 (just nine days later), Ali committed suicide in that cell. It remains unclear how RCSD custody/medical staff failed to notice Ali performing the act of strangulation over a span of several minutes which was indeed captured on video by surveillance footage inside her cell. Ali was only 21 years old when she died.

Now that you know who Ali was and how Ali’s life was cut short, please scroll to read Sheriff Bianco’s response to Ali’s death, as well as his utter disrespect towards folks who suffer from mental illness. There is nothing “silly” about holding the government accountable when mentally ill inmates who are acutely suicidal are given the means to end their life while in the government’s custody. What these government failures amount to are 14th Amendment violations arising from the government’s failure to protect those in its custody from harm, and for its failure to provide mental health care to those in its custody.”

Here are some of the images I used in the post to expose the misrepresentations (see Figures 1, 2, 3).

While trial may be a good 16 months away from the press conference, this early media engagement assists with shaping the public’s perceptions, and at times (such as in Alicia’s case) correcting biased perceptions by reshaping the narrative.

Lawsuit: Storytelling via the pleadings

Another opportunity to humanize a plaintiff in a civil rights case is at the pleading stage. The lawsuits I file in federal court are typically 60 pages long and include at a minimum ten legal causes of action, ranging from violations of the decedent’s Fourteenth Amendment rights to the parents’ wrongful death claims. The complaints tend to be long because of the allegations I include to support the Monell claims, i.e., 42 U.S.C. § 1983 claims against the municipal defendants.

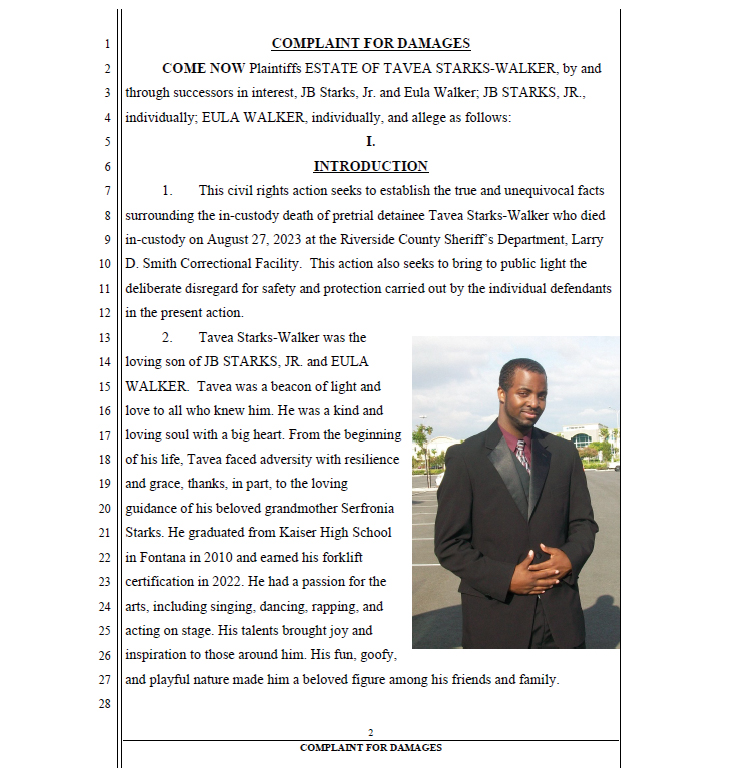

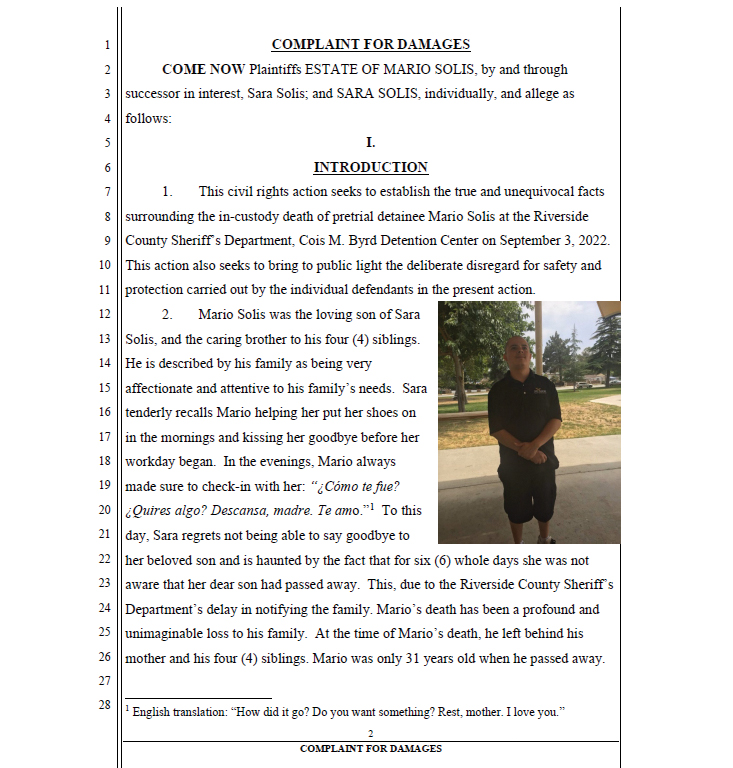

No matter the length of the complaint, I always ensure that page two of the complaint is dedicated to telling the decedent’s story, albeit a one-page abbreviated version. Why do I do this? To ensure that the storytelling continues from the inception of the case into the litigation of the case. The families will provide me with their favorite photograph of their loved one and will respond to a simple prompt: “I would very much appreciate if you could lend me a few words that you would use to describe the type of person Mario was, what he stood for, and how much he meant to you.”

Here are examples of “page two” from two of my jail death cases (Figures 4 and 5).

Trial

Civil-rights cases often gain a lot of media attention before they are filed and certainly before they are tried. Because of this, your prospective jurors may know a thing or two about the case before they are selected as jurors – both the good things and the not-so-good things. Civil-rights trials typically follow oral argument on a motion in limine or two or three relating to the decedent, e.g., criminal history, substance abuse, employment background. Ultimately, all issues need to be confronted head on during voir dire.

In my civil-rights trials, I begin my voir dire by sharing one of my life’s mottos: “You are not your worst mistake.” From there, I explore the jurors’ perceptions regarding my decedent’s not-so-good things. This exploration is at times dark and uncomfortable, but necessary. As an example, in jail-death cases, I will ask questions regarding whether jurors believe it is sinful to commit suicide; whether a person who commits suicide is selfish; whether inmates should enjoy the same rights as those of us who are not incarcerated, and if so, where do we draw the line; and so on.

In my practice, most of the families I represent are monolingual Spanish-speakers and some of the decedents are undocumented. I, myself, did not learn English until I was seven years old and my family is of immigrant background. And so, while some of the jurors’ responses may be uncomfortable to hear, they are necessary.

Denisse O. Gastélum

Denisse O. Gastélum is the founder and lead trial attorney at Gastélum Law, APC, where her practice focuses primarily on civil rights/police misconduct, sexual abuse and wrongful death.

Ms. Gastélum is a Past President of the Mexican American Bar Association and the Latina Lawyers Bar Association. She is the current President of California La Raza Lawyers Association, and currently serves on the Board of Directors of the ACLU of Southern California, the National Police Accountability Project, the Los Angeles County Bar Association, the Consumers Attorneys Association of Los Angeles, and the Consumer Attorneys of California. She received her B.A. at UCLA and her J.D. from Loyola Law School.

Copyright ©

2025

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine